What makes an English saber legendary? Imagine the mist-covered plain, a regiment galloping, and the curved flash of a blade cutting through the air: English sabers were born for that conjunction of speed, forging artistry, and military strategy. This article guides you from their origins and standardization to modern replicas, with technical analysis, comparisons, and conservation tips, all so you can understand why these sabers marked an era.

Historical Evolution of English Sabers

Standardization, the influence of visionary officers, and adaptation to different theaters of war turned English sabers into key pieces between the 18th and 19th centuries. Below is a detailed chronology that highlights the milestones and models that defined their design and use.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| 17th Century | |

| Traditional Use | English cavalry knights carried their own sabers and equipment into combat. |

| Late 17th Century | With the professionalization of armies, regiments began to supply weapons to paid soldiers, and governments standardized armament through state contracts. |

| Late 18th Century (1780s–1790s) | |

| 1788 | The British Board of General Officers established fixed patterns for heavy and light cavalry; first attempt at standardization with multiple variations.

|

| June 1793–1795 | Netherlands Campaign: Major John Gaspard Le Marchant observed Austro-Prussian superiority and pushed for improvements in British cavalry training and equipment. |

| 1793 (Spain) | The “General Ordinances of the Naval Armada” prohibited non-gilded swords and buckles for the Armada and Army; sabers were not mentioned, although they were used by officers in boarding actions. |

| 1796 | Le Marchant published a manual of mounted fencing and contributed to the first British military academy. He introduced two key models:

|

| 1798 | First edition of “The Art of Defence on Foot with the Broad Sword and Sabre” by Charles Roworth, a reference work for British infantry fencing. |

| Early 19th Century (Napoleonic and Post-Napoleonic Era) | |

| 1803 | Manufacture of the British Model 1803 Infantry Officer’s Saber; producers like Richard Johnston in London. |

| 1804 | Third edition of “The Art of Defence” by Roworth. |

| May 1807 | By the Treaty of Tilsit, the United Kingdom sent 6,000 Model 1796 sabers to Colberg (Prussia) to arm Von Schill’s and Blücher’s hussars. |

| 1811 | Prussia copied the British 1796 saber and began manufacturing the “Model 1811” or “Blücher Saber.” |

| 1813 | Great Britain sent an additional 10,000 units of Model 1796 sabers to Prussia. |

| 1814 | Ramón de Salas stated that Spanish cavalry generally used “English swords and sabers.” |

| 1815 (Waterloo) | At Waterloo, British 1796 and Prussian 1811 sabers (copies of the English ones) confronted Napoleonic forces. |

| 1817 | Henry Angelo Senior’s son developed the official British infantry sword system, based on his father’s work. |

| 1821 | Introduction of the Pattern 1821 Cavalry Sabers (heavy and light) gradually replacing those of 1796: heavy pattern (905 mm blade) and light (approx. 795 mm); lighter officer models with pipeback or grooved blades. |

| 1824 | Fourth edition —considered the most complete— of “The Art of Defence on Foot with the Broad Sword and Sabre” by Roworth, published in New York. |

| 1832 | Ángel Laborde (Spanish Squadron Chief) ordered the translation and publication of an “Instruction for the Exercise of the Saber” based on British Infantry, emphasizing the handling of bladed weapons in naval boarding actions. |

| 1833–1840 | Carlist War: English models from 1796 again reached Spain, acquired by the Spanish government. |

| Mid-19th Century | |

| 1850 | Records of national production of the Model 1827 saber at the Toledo Factory, with blades dated 1850. |

| 1853 | Approval of the British “Enfield” saber (Pattern 1853) for the British cavalry; 900 mm blade. |

| 1853–1856 (Crimean War) | Some hussars still used the 1796P LC. The Pattern 1853, introduced before the war, was used by approximately half of the riders in the Charge of the Light Brigade. |

| 1853–1866 (Spain) | The “Illustrated Dictionary of Artillery” named and illustrated the 1796 Line Cavalry model as “English Sword.” |

| 1857 | The English Model 1827 Naval Officer’s saber became widespread and was regulated for certain officers of the Spanish Navy; later named “Model 1857” in the Toledo Factory’s tariff (1871). |

| 1861–1865 (American Civil War) | Large volumes of the Pattern 1853 were sold to Confederates and Unionists; British naval cutlasses surpassed those of the South. |

| Late 19th Century and 20th Century | |

| 1864 | The guards of the Pattern 1853 sabers were modified to “bowl” designs. |

| 1870s | Some regiments continued to use the Pattern 1853. |

| 1881 | Brigadier Barrios confirmed the regulation of the Model 1857 saber for certain corps of Spanish Navy officers. |

| Early 20th Century | The saber ceased to be a primary combat weapon and transitioned to a mostly ceremonial role in parades and military traditions. |

| 1931 (Spain) | After the proclamation of the Republic, the royal crown on the guard of the “Md. 1857” saber was replaced by a mural crown. |

| After the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) | A sword-saber was produced for the Navy with a Puerto-Seguro model blade and an imperial crown over the anchor. |

Key Models and Why They Matter

The 1796 models (light and heavy), the 1821 pattern, and the 1853 Pattern mark the British evolution: from the acceptance of the curve as an advantage for the rider to the search for a balance between cutting and thrusting. These designs influenced allies and adversaries, and their study helps identify original pieces and faithful replicas.

Quick Technical Comparison

| Model | Blade Length (approx.) | Curvature | Preferred Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1796 Light Cavalry | ~810–900 mm | Pronounced curve | Cuts from the horse’s flank; versatile for light thrusting |

| 1796 Heavy Cavalry | ~940 mm | Less curved, straighter | Forceful strike and thrust in formations |

| Pattern 1821 (light/heavy) | ~795 / 905 mm | Moderate curvature | Compromise between cutting and thrusting; officer versions more polished |

| Pattern 1853 (Enfield) | ~900 mm | Moderate curvature | Design for modern and naval context; functional balance |

- 1796 Light Cavalry

-

- Blade length: ~810–900 mm

- Curvature: pronounced

- Tactical use: effective cuts from horseback.

- 1796 Heavy Cavalry

-

- Blade length: ~940 mm

- Curvature: subtle

- Tactical use: breaking formations and thrusts.

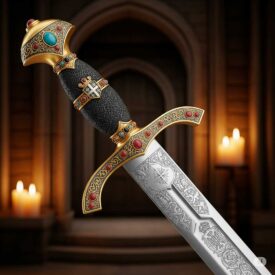

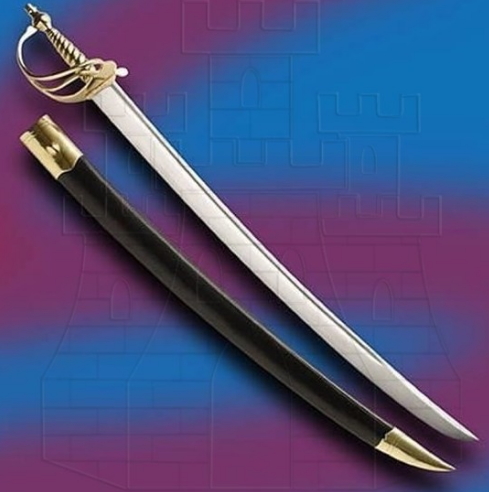

How to Recognize an Authentic English Saber or a Faithful Replica

Identifying an English saber requires observing the blade, guard, hilt, and scabbard. The blade is usually made of carbon steel with fullers in many patterns; the guard varies from simple quillons to full cups depending on the model and date. Officer versions often feature engravings and finer finishes.

Key details to inspect:

- Manufacturer’s mark or stamp: some English and continentally accepted manufacturers leave dated marks.

- Blade type: fullered or pipeback; the presence of a fuller and its treatment helps identify the period and pattern.

- Hilt: fluted wood and leather or wire-wrapped hilts; officers typically have more ornate hilts.

- Scabbard: iron or reinforced leather with brass tips depending on the era.

Here I insert a historical replica for you to visualize the proportions:

Manufacturing and Materials: What Made These Sabers Endure

The craft of the swordsmith in Great Britain combined tradition and technological adaptation. Although many blades were made of carbon steel, forging, tempering, and annealing determined flexibility and sharpness. High-carbon steel, mentioned in numerous current catalogs, reproduces that appearance and behavior.

Elements of construction:

- Carbon steel: provides edge hardness and malleability during tempering; requires maintenance to prevent corrosion.

- Guards and mounts: brass, iron, or steel, designed to protect the hand or to facilitate quick use when mounted.

- Scabbards: leather with metal reinforcements or entirely metal scabbards; brass tips were common and decorative as well as practical.

Tactics and Technique: The Use of the Saber in Mounted Combat

The saber is, par excellence, the rider’s weapon. Its curvature is designed to transform inertia into a clean cut; the length allows maintaining distance or striking from the horse’s tail without losing control. Manuals of the time and fencing treatises established exercises and attacks that optimized the advantage of being mounted.

- Cutting blow: leveraging the horse’s trajectory to multiply force.

- Short thrust: in models with a spear point, the aim was to penetrate vulnerable targets.

- Defense with guard: closed guards protected against counterattacks and allowed quick recovery of position.

Technique evolved according to the theater: on European plains, cutting from a gallop was favored; in enclosed or naval spaces, shorter and more maneuverable sabers predominated.

Replicas, Conservation, and Collecting

Today, English sabers are found again as replicas for historical reenactment, historical fencing practices, and collecting. A well-made replica respects dimensions, curvature, and finishes, and uses materials that emulate the feel of the original.

Tips for preserving replicas and historical pieces:

- Regular cleaning: clean the edge with protective oil after each handling and remove traces of moisture.

- Storage: avoid humidity and prolonged contact with deteriorated leather; use supports that do not deform the blade.

- Minimal restoration: seek specialists for any repairs; preserve historical patinas when they belong to authentic pieces.

Comparison for Collectors

| Aspect | Historical Piece | Modern Replica |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Forged steel with historical treatments | Carbon steel or stainless steel tempered according to purpose |

| Details | Original engravings and patinas | Decorative finishes; some models reproduce engravings |

| Use | Decorative/collection, occasionally functional | Reenactment, practice of historical martial arts, display |

- Historical Piece

-

- Material: forged steel

- Function: original combat and historical value

- Modern Replica

-

- Material: carbon steel or stainless steel

- Function: practice and aesthetics

How to Choose a Replica or Piece for Your Collection

Choose according to purpose: exhibition, practice, or study. Prioritize dimensional fidelity for historical practices and tempering quality if you will use it in exercises. Avoid pieces with extensive corrosion or modifications that alter structural integrity.

If you seek specificity, identify the pattern (1796, 1821, 1853) and check lengths and curvatures. Technical descriptions and stamps are your best guide. In many modern catalogs, you will find manufacturer indications and composition—use them for comparison.

Resources for Further Reading

Books from the era, fencing manuals, and historical manufacturer catalogs offer the documentary basis for understanding the design and use of English sabers. Military treatises and arsenal inventories also facilitate tracing how pieces traveled and adapted to other armies.

After reviewing history, technique, and conservation, I leave you with a set of selected replicas and related categories for you to explore in detail:

VIEW MORE ENGLISH SABERS | VIEW SABERS FROM OTHER COUNTRIES

English sabers are more than just tools of war: they are pieces of engineering, tradition, and aesthetics. Knowing their evolution, distinguishing patterns, and preserving replicas or originals connects you with a history of technique and bravery that still resonates. If you appreciate craftsmanship and history, studying these sabers will give you keys to understanding not only war, but also the material culture of an era that continues to inspire.