Legend has it that in the heat of the battles that took Alexander III of Macedon beyond the limits of the known world, the sword shining in the hands of his warriors cut like the wind. That image — of a curved blade, powerful cutting edge, and almost ceremonial aesthetic — has historically linked the name of Alexander the Great with blade shapes such as the kopis, the makhaira, and, in the modern imagination, the falcata. In this text, we explore that connection: what is myth, what is history, and how these weapons are represented today in replicas for collectors and reenactors.

Unified Chronology of the Falcata

Ordered and synthetic chronology based on the provided sources.

| Period / Date | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| 10th Century BC | Possible remote origins of asymmetrical curved blades (e.g., machaira or kopis) on the Balkan coasts around the Adriatic. |

| 7th Century BC | This type of curved sword spreads towards Greece and the Italian Peninsula. |

| 5th Century BC (or late 6th Century BC) | The falcata appears in the Iberian Peninsula; Iberians adapt it to a shorter model and, sometimes, double-edged. Origin hypothesis: influence of Hallstatt knives, Greek weapons (kopis, makhaira), or Mediterranean contacts with Celts, Greeks, or Etruscans. |

| 5th Century BC | Approximately in this century, the Celtic sword known as La Tène also emerges. |

| Peloponnesian War / 5th–4th Century BC | Iberian mercenaries used the falcata in Mediterranean conflicts, including the Peloponnesian War (according to references of Iberian mercenaries in classical conflicts). |

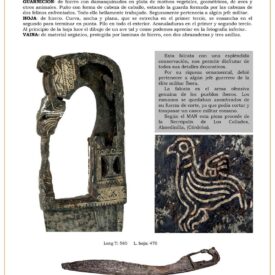

| 5th–3rd Century BC | Falcata specimens date from this period; archaeological finds like the falcata from the Necropolis of Los Collados (Almedinilla) belong to this chronology. |

| 4th–3rd Century BC | Falcata from this period are preserved in archaeological deposits and funerary contexts that allow studying their shape and technique. |

| 216 BC | In the Battle of Cannae, the falcata, wielded by Iberian troops in Hannibal’s service, played a crucial role in the Carthaginian victory over Rome. |

| 3rd Century BC | Roman soldiers arrive in the Iberian Peninsula; observing the effectiveness of weapons like the falcata, they adopt characteristics and order the reinforcement of shield edges with iron to counteract its cut. |

| Punic Wars (First and Second) | Iberian mercenaries used the falcata in these conflicts against and in the service of Rome and Carthage. |

| Until early 1st Century BC (time of Quintus Sertorius) | The use of the falcata persists until Romanization and the adoption of the gladius (of Celtiberian/La Tène origin) cause its progressive abandonment. |

| Mid-1st Century BC | The falcata ceased to be widely used due to the integration of Iberian territory into the Roman sphere. |

| 19th Century | The term “falcata” is introduced into archaeological literature to describe this sickle-shaped blade; classical references spoke of machaera or machaera hispaniensis. |

| Romanticism (19th Century) | The falcata is mythologized as a symbol of the Iberian warrior spirit and resistance against foreign domination. |

| 2004 | The iconography of Alexander the Great in popular cinema popularized the use of curved blades similar to the falcata, incorporating them into the collective imagination about the weapons of the period. |

| 2010 | Television projections and historical series contribute to disseminating the image of the falcata as a representative weapon of certain Iberian peoples, although reenactments may mix chronologies and ethnicities. |

| Present Day | The falcata continues to be the subject of archaeological study and artisanal reproduction; experimental archaeology allows evaluating its effectiveness and traditional forging techniques are adapted for modern replicas. |

What distinguishes the falcata from other curved swords?

The falcata has an unmistakable silhouette: a blade widened towards the tip, a pronounced curvature, and, in many cases, a weight concentrated towards the end that increases the impulse of the cut. This shape morphologically aligns it with other curved blades of the Mediterranean world, but its identity is forged in the Iberian Peninsula.

Main characteristics:

- Sickle-shaped blade: the curvature and widening facilitate powerful cuts, especially in short thrusts.

- Robust hilt: designed to provide control and impact resistance.

- Relatively short length: favors handling in confined spaces and in close-quarters combat.

Brief comparison: falcata vs kopis vs makhaira

The Greek kopis and makhaira are curved blades with distinct traditions; the falcata shares the principle of concentrated cutting at the tip, but differs in proportions and details of hammering and central rib reinforcement. In summary, these are families of curved blades with local developments.

Alexander the Great: did he carry a falcata?

This is where history mixes with popular image. Contemporary sources to Alexander describe curved weapons like the kopis, common among hoplites and light cavalry. The direct association between Alexander and the Iberian falcata is rather a later construction: the falcata has been incorporated into the modern imagination as a synonym for a powerful curved sword.

Pictorial and cinematographic re-elaboration has united the figure of the conqueror with blades of falcata-like aesthetics. These representations do not necessarily accurately reproduce the Macedonian armament of the 4th century BC, but they do convey the idea of a sword capable of mowing down shields and making a dent in the enemy formation.

Why the association emerged

- Visual symbolism: the curved shape is spectacular and easy to identify in film and reproductions.

- Influence of replicas: many artisans have taken the falcata as an aesthetic basis for editions dedicated to Alexander the Great.

- Terminological confusion: classical terms like machaera encompass different types of curved blades, which facilitates the mixture of concepts.

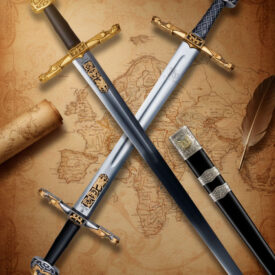

After this historical overview, many enthusiasts seek to take home a replica that evokes the epic. Modern replicas of the Alexander the Great falcata combine design and symbolism: decorative ribs, grooved blades, hilts with animal motifs, and black and gold finishes.

Construction of a replica: materials and techniques

The manufacture of current replicas mixes tradition and contemporary techniques. Forging in carbon steel or stainless steel, heat treatments to balance hardness and toughness, and black or gold finishes for aesthetics. The result is a piece that honors the original silhouette, suitable for display and, in some cases, for light cutting practices.

Elements to consider when observing a replica

- Type of steel: carbon steel offers better edge retention and historicity; stainless steel facilitates preservation.

- Heat treatment: crucial so that the blade is neither too fragile nor too soft.

- Assembly: the joint between blade and hilt determines durability.

- Finish: patinas, acid baths, and gilded or nickel-plated details provide the “Alexander” aesthetic.

Maintenance and conservation for replicas

A well-cared for replica is a tangible story. Keeping the blade clean, oiled, and protected from moisture prolongs the life of the steel. Wooden or synthetic material handles require gentle treatments; avoid abrasive products that can damage reliefs.

How to distinguish a decorative replica from a functional replica

A piece made only for decoration usually has visible welds, low-quality steel, and no heat treatment. Functional replicas specify the type of steel, come sharpened in a controlled way, and show documentation about the heat treatment.

Quick tips

- Look for technical references in the product description.

- Inspect the quality of the finish on the hilt and pommel.

- Assess the weight and balance: a well-built falcata has its mass concentrated towards the tip but remains manageable.

Historical use and practical value

In combat, the falcata proved its effectiveness in cutting through light protections and finishing maneuvers after formations broke. In the hands of Iberian mercenaries or allied soldiers, its design provided a tactical advantage in engagements on uneven terrain or in close-quarters combat.

The falcata in popular culture and its link with Alexander the Great

Films and series have ended up fixing in the collective mind the image of an Alexander wielding a stylized curved blade. This association is powerful: it evokes conquest, exoticism, and military dominance. From a cultural point of view, the falcata functions as a symbol that synthesizes strength and uniqueness.

Implications for collectors and reenactors

Choosing a replica is deciding what story you want to tell. Are you looking for technical fidelity? Prioritizing aesthetics? Or are you driven by the romantic idea of holding an object that evokes Alexander the Great? Each replica tells a version of that story.

Myths worth debunking

- The falcata was Alexander’s personal weapon: unlikely; Alexander and his officers used Hellenic and Macedonian weapons, although falcata aesthetics appear in some reconstructions.

- A falcata was always superior to the gladius: both are different solutions for different contexts; the falcata is excellent for powerful cuts, the gladius for thrusts in closed formations.

- All Iberians used the falcata: there were many regional variants and blade types in the Iberian Peninsula.

The relationship between falcata Alexander the Great mixes history, aesthetics, and mythology. Understanding it requires distinguishing historical Mediterranean weapons, appreciating the Iberian tradition of the falcata, and recognizing the role of modern imagination in creating epic images. Whether you are looking for a replica for display or a piece that narrates the legend, the essential thing is to value the history behind the blade and the respect for the techniques that made it possible.