When we hear “Japanese sword,” our minds most likely picture the unmistakable silhouette of a katana. And although this term has become almost synonymous with the swords of the Land of the Rising Sun, the world of nihontō—the technical and traditional name for any Japanese sword—is much vaster and more thrilling than you might imagine. Get ready for a fascinating journey through the history, technique, and soul of these legendary works of art!

The name of Japanese swords is highly varied, depending on their length and function. Among the most important are Katanas, Naginatas, Nodachis, Sais, Shirasayas, Tachis, Tantos, Wakizashis, Iaitos, Bokkens, Nagamakis, and many other weapons that made up the arsenal of warriors in feudal Japan.

Evidently, the best-known Japanese weapon is the katana, a powerful weapon and a true work of art that represents a culture, traditions, and millennia-old values rich in spirituality, humanity, and martiality. Japanese weapons also represent a sacred symbol of power and bravery, transcending their purely warlike function to become cultural icons.

A Journey Through Time: The Historical Evolution of Japanese Swords

The history of Japanese swords is a reflection of Japan’s own history, marked by war, peace, and a constant quest for artisanal perfection. Each period left its mark on the design, forging, and purpose of these legendary weapons.

The Beginnings: Kofun Period (250–538) and Asuka (538–710)

The first swords in Japan were not native but imported from China and Central Asia. In the Kofun Period, these straight swords, often made of bronze and later iron, were mainly used in religious and funerary ceremonies, forming part of the noble grave goods in their tombs. They were more symbols of status and power than combat tools. From the Asuka Period, local manufacturing began to take shape, giving rise to the short and narrow swords known as chokutō, marking the beginning of a unique metallurgical tradition.

Towards the Curve: Nara Period (710–794) and Heian (794–1185)

In the Nara Period, local swords grew in length and width, already serving as tools for war. The influence of Buddhism also became evident, introducing straight, double-edged swords with decorations that, though less ergonomic, had great symbolic value for the upper classes. However, the most significant change occurred in the middle of the Heian Period. The sword became increasingly crucial on the battlefield, and imperial stability allowed master smiths to refine their techniques. It was then that the straight, double-edged sword gradually gave way to the characteristic curved, single-edged steel sword. Popular swords from this era include the tachi, a long and heavy sword ideal for mounted samurai, and the uchigatana, shorter and suitable for foot combat. Legend even attributes the invention of the katana to the swordsmith Amakuni, from the division of the ancient ken.

The Apex: Kamakura Period (1185–1333)

This period is fundamental, as it is when the katana proper and the wakizashi gained immense popularity, becoming the predominant sword styles. Foot combat gained greater relevance, and the art of sword making flourished, reaching its peak between the 12th and 13th centuries. Even Emperor Gotoba promoted sword forging, gathering the best smiths from the provinces. Legendary names like Masamune, Yoshimitsu, and Yoshihiro emerged in this “great era of Japanese swordsmiths,” whose works are now national treasures. The tanto also became popular during this time, establishing itself as an essential dagger in the samurai arsenal.

Refinement and Challenges: Muromachi (1336–1573) and Azuchi-Momoyama (1573–1603) Periods

Katana and wakizashi remained the dominant styles, with continuous improvements in forging and polishing techniques. However, the Muromachi saw the appearance of the uchi-gatana and the shinogi-zukuri wakizashi. Constant civil wars, such as the Mongol invasions or the Sengoku Jidai period, led to a decline in quality, prioritizing quantity over excellence and sometimes using inferior materials. The sword tradition dispersed, leading to the production of more short swords and auxiliary daggers like the kodachi and tanto. Despite the challenges, the demand for weapons kept smiths busy, although artistic perfection was often sacrificed for pragmatic needs.

Status Symbol: Edo Period (1603–1867)

With the arrival of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Japan experienced a period of relative peace. Swords, especially the katana and wakizashi, perfected their forging and polishing techniques, but their role shifted from being purely warlike to more ceremonial. It was in this era that the famous daishō—the iconic pair of katana and wakizashi that samurai wore together—became a status symbol, a mark of their class and honor. The blades of this period, known as “Shinshinto” (brand-new swords), often sought extravagant shine, showing their new purpose as part of dress uniforms and collector’s items, rather than as daily weapons on the battlefield.

Modernity and Preservation: Meiji (1868–1912) to Reiwa (From 2019)

The Meiji Restoration marked the end of the samurai era and the modernization of Japan, which led to a decline in the practical use of swords. In 1876, an Imperial Edict (Hito-rei) banned the use of swords by warriors, a devastating blow to the industry. However, to ensure the survival of the art, the Emperor appointed master swordsmiths as “Imperial Craftsmen,” recognizing the intrinsic cultural value of these pieces. Although their use in combat diminished, swords continued to be made for cultural and historical reasons during the Taishō and Shōwa periods. During World War II, there was a large production of Gunto swords (Japanese army swords), though often industrially made (showato) and of lower artistic quality than traditional ones, prioritizing quantity for the war effort.

After the war, the Allied forces initially banned and destroyed much of the Japanese arsenal. However, the cultural importance of the sword led to a gradual recovery. A 1953 law allowed manufacturing to resume under strict rules: only accredited swordsmiths with at least five years of apprenticeship, with production limits and mandatory registration. In 1960, the Japanese Society for the Preservation of Sword Art (NBTHK) was founded to safeguard the tradition, operating furnaces for tamahagane, managing museums, and organizing competitions for masters. Today, in the Heisei and Reiwa periods, Japanese swords continue to be made as a traditional art. They are no longer weapons of war, but collectibles, works of art, and tools for martial arts practice. The sword remains a profound symbol for the Japanese, and its best examples are considered national treasures, admired globally for their artistic beauty, historical value, and the properties that made them so formidable and effective on the battlefield.

An Arsenal of Forms: The Different Types of Japanese Swords

Beyond the omnipresent katana, the world of Japanese swords is rich in variety and purpose. Each type was designed with a specific function in mind, adapting to different combat styles and social needs.

Chokutō (直刀)

The Chokutō are the oldest swords, straight and single-edged, inspired by Chinese and Korean models, dating from before the 10th century. They were the precursors to the curved swords that would define Japanese tradition. They are no longer made, but their historical importance is undeniable as the starting point of sword metallurgy in Japan.

Tachi (太刀)

Considered the first Japanese sword forged with curvature, the Tachi is longer and thinner than the katana, with the greatest curve in the first third of the blade. It was mainly intended for mounted samurai and was worn with the edge down (ha-o-shita), making it easier to draw from horseback. Its elegance and length made it an imposing weapon on the battlefield.

Katana (刀)

The Katana is, without a doubt, the most iconic and recognized sword worldwide, a true symbol of the samurai. It has a curved, single-edged blade about 60 cm long (though it can vary). Its main feature is its unmatched edge, achieved through differential clay tempering and meticulous hand polishing. Samurai wore it in the obi (belt) with the edge up (ha-o-ue) for quick and effective drawing, allowing for an instant cut upon unsheathing. It is a weapon of great power and a true work of art that represents a culture, traditions, and millennia-old values rich in spirituality, humanity, and martiality.

Wakizashi (脇差)

A sword similar to the katana, but shorter, with blades ranging from 30 to 60 cm. Its smaller size made it ideal for combat in confined spaces, such as inside houses or dense forests. Together with the katana, it formed the daishō, the samurai’s traditional pair of swords, symbolizing their honor and status. It could also be carried by merchants and was the weapon used for seppuku, the ritual suicide to preserve honor, highlighting its deep connection with samurai culture.

Tantō (短刀)

A dagger or knife with a slightly curved blade less than 30 cm long. It was invented during the Heian period and was mainly used as a last-resort weapon or for close combat. It could have a guard (tsuba) or not, adapting to different mounts and purposes. With the start of the Kamakura era, tanto were also made to be decorative, becoming objects of art and status. The kaiken was an even smaller version, used by samurai women for self-defense.

PROFESSIONAL ORCHID TANTO

Professional Orchid Tanto with K120 C hand-forged and folded carbon steel blade.

Ninjatō (忍者刀)

A short, straight-bladed sword, less than 50 cm, associated with ninjas. It is often attributed a large square guard that could aid climbing or serve as support for jumping walls. However, its origin remains a mystery and lacks solid historical documentation, being more an element of modern popular culture than a historically documented ninja sword.

Uchigatana (打刀)

A predecessor of the katana, of inferior quality in its beginnings, used by lower-ranking warriors or as a secondary weapon. Its design evolved and laid the foundation for the katana as we know it. Recently, it has gained popularity thanks to its appearance in video games and other cultural representations.

Ōdachi (大太刀) and Nōdachi (野太刀)

Exceptionally large swords, with blades exceeding 90 cm. The nōdachi refers to a “field sword,” used in large battlefields, and its handling was so challenging that it sometimes required help to draw, often being carried by an assistant. These massive swords were used to charge enemy formations or for fighting cavalry, requiring considerable strength and skill from their wielder.

Nagamaki (長巻)

A polearm similar to a spear, with a long blade (between 70 and 100 cm) and an equally long handle, often wrapped like a katana’s grip. It was used by infantry warriors between the 12th and 14th centuries, and from it derived the naginata. Its design allowed for distance combat with the ability to make wide and powerful cuts.

Naginata (長刀)

The Naginata is a weapon used by samurai in feudal Japan, consisting of a blade fixed to a long shaft. It resembles a European halberd, but with only a curved blade and a tip at its end. It was particularly popular among warrior monks (sōhei) and samurai women (onna-bugeisha), who used it skillfully to keep opponents at bay. Its versatility made it effective against both infantry and cavalry.

NAGINATA

Naginata sword mounted with long tang and 1065 carbon steel blade tempered using the traditional claying method.

Training Swords

For martial arts practice and safe training, unsharpened versions of these weapons were developed, allowing practitioners to develop their skills without risk of serious injury.

-

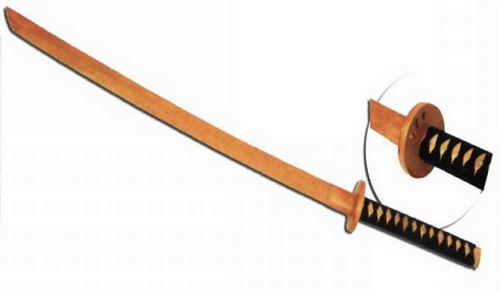

- Bokken (木剣): A wooden version of the katana, which became popular in the Muromachi period (1936/1600 AD) when different Ryu began teaching the art of KenJutsu. It is famous for being the preferred weapon of the legendary Miyamoto Musashi, who used it in numerous duels. Its weight and balance simulate those of a real katana, making it an indispensable training tool.

- Iaitō (居合刀): A metal sword without an edge, used in iaidō, a discipline focused on the art of quick drawing, cutting, and sheathing. It allows practitioners to perfect technique and concentration without the danger of a sharp blade.

- Shinai (竹刀): Made of bamboo slats bound with leather, it is the sword used in kendo, a modern martial art centered on sword combat. Its flexible design allows for safe strikes during practice, reducing the risk of injury.

Other Traditional Japanese Weapons

In addition to swords, the Japanese arsenal included a variety of weapons reflecting the ingenuity and adaptability of its warriors, often derived from agricultural or everyday tools.

Bo-Kun (棒)

A very sturdy turned wooden staff about 1.80 meters long and 2.5 to 3 cm in diameter. This item was used by fishermen and villagers to transport items and goods, making it a common and discreet tool. In feudal Japan, there were experts who handled this instrument so skillfully that, when facing a samurai warrior armed with a sword, they emerged victorious, demonstrating the effectiveness of improvised weapons.

Eku (櫂)

An ancient Okinawan Kobudo weapon that originated from an oar, about 160 cm long. According to myth, the oar was traditionally adapted for use as a self-defense weapon by fishermen against enemies armed with more conventional weapons. One end has a smooth blade on one side and angled on the other, sharpened at the tip. Although it is made of wood, its sides have a certain edge, making it a surprisingly effective weapon in expert hands.

Hanbo (半棒)

A rounded staff about 90 cm long. The Hanbo can be used with one or two hands. It is used for movements similar to those of the Jo, and techniques such as atemi (strikes to vital points), strangulations (jime), joint locks (Kansetsu), blocks (Dome), etc. It is a versatile weapon for close combat.

Jo (杖)

A wooden staff shorter than the Bo-Kun and longer than the Hanbo, generally about 128 cm. It is one of the most fundamental weapons in Japanese martial arts, especially in Jōdō, where it is used to defend against sword attacks. Its intermediate length allows for both long-range attacks and close combat techniques.

Kama (鎌)

A long-handled sickle used to cut cereals; the difference from the Western sickle is the curvature of the kama, which starts at the handle. This agricultural tool was transformed into a formidable weapon in the hands of martial arts practitioners, allowing for hooks, cuts, and effective blocks.

Nunchaku (ヌンチャク)

This weapon consists basically of two very short sticks, between 30 and 60 cm, joined at the ends by a rope or chain. It is a very versatile weapon, adapting to situations against one or several attackers at short or long distances, both in defense and attack, developing great striking power. It became popular worldwide thanks to martial arts movies.

Sai (釵)

The Sai is a dagger without an edge but with a sharp point and two long side guards, tsuba, also pointed, attached to the handle. Originating from Okinawa, it was mainly used to block and disarm weapons, as well as to strike and stab. Its unique design makes it a very effective defensive and offensive weapon.

Tambo (短棒)

The Tambo is a stick about 30–50 cm long, similar to a short baton. The purpose of the tambo was to strike limbs and bony points with precision and speed, being a discreet but forceful weapon for close combat and self-defense.

Tonfa (トンファー)

Also known as Tuifa, it is a stick about 50 cm long and a handle about 15 cm, perpendicular to the main body. It is one of the most important weapons in karate and jiu-jitsu for its ability to face swords, allowing powerful blocks, rotary strikes, and levers. Today, it is widely used by police forces in many countries.

Yubibo (指棒)

A stick of 13 to 15 cm, with two holes dividing it into three sections called Kontei at the ends and Chukon bu in the central part between the two holes. It is a small hand weapon used to strike pressure points and perform control and submission techniques, often hidden and used in hand-to-hand combat.

The Master’s Touch: The Art and Science of Forging

The creation of a traditional Japanese sword is a process bordering on alchemy, combining the mastery of the smith with a deep knowledge of materials and a dedication spanning generations. It is an art that fuses metallurgical science with spirituality and tradition.

The Heart of Steel: Tamahagane and Tatara

It all begins with tamahagane, a high-carbon steel considered the “jewel steel” for its purity and quality. This material is produced in a special furnace called tatara, a kind of primitive clay blast furnace used for centuries. For days, charcoal and iron sand are burned at controlled temperatures, allowing the iron to combine with carbon and many impurities to be eliminated. The resulting tamahagane is a porous block with quality variations inside, which the smith must carefully evaluate and select for each part of the sword.

The Selection and Folding of the Steel

The smith carefully selects pieces of tamahagane, combining high-carbon steel (hard and sharp, but brittle, ideal for the edge) with low-carbon steel (softer, elastic, and resistant, perfect for the core). These pieces are heated, hammered, and crucially, folded and welded repeatedly. This process, known as orikaeshi tanren, not only removes impurities and strengthens the steel, but also creates the characteristic layered pattern (“hada” or “jitetsu”) on the blade’s surface, doubling the number of layers with each fold until thousands are reached. This folding not only improves the steel’s homogeneity but also contributes to the blade’s aesthetic beauty.

The Construction of the Blade (Tsukuri-Komi)

Japanese swords are not a simple piece of metal, but a complex structure composed of different types of steel to optimize their properties:

- Kawagane (skin-steel): The outer coating, made of carefully selected and folded steel sheets, providing surface hardness and wear resistance.

- Shingane (core-steel): The elastic core of the blade, made of low-carbon steel, folded and hammered to reduce impurities. This core absorbs impacts, preventing the blade from breaking.

- Hagane (blade-steel): An even harder, carbon-rich steel, often used for the edge itself, giving it extreme hardness and exceptional cutting ability.

The kawagane is bent into a “U” shape and the shingane is inserted inside, fusing through heat and percussion to create a blade with a very hard exterior and an elastic core, capable of absorbing impacts without breaking. Legendary masters like Masamune used up to seven different steels in a single sword, demonstrating the complexity and refinement of this technique. The tip (kissaki) is usually made only of hard steel, giving it great penetrating ability.

The Tempering: Creating the Hamon

This is the most critical and mysterious phase: differential tempering. The blade is covered with a layer of special clay (a mixture of clay, ash, charcoal, and water), leaving only a thin line exposed along the future edge. Then, the blade is heated to a precise temperature and quickly cooled in water or oil. This sudden temperature change alters the molecular structure of the steel, causing the final curvature of the blade (sori) and revealing possible defects. The rapid cooling “locks” the carbon atoms in the iron’s crystalline structure, drastically increasing the steel’s hardness at the edge (martensite). In contrast, the areas covered with more clay cool more slowly, remaining softer and more elastic (pearlite).

The visible result of this process is the hamon, the wavy line that separates the edge from the body of the katana. It is a unique pattern formed by martensitic crystals concentrated at the edge (ha-saki), giving it extraordinary hardness and a lasting ability to maintain its edge. The uniformity of the hamon is a key sign of quality, and its shapes can vary from straight (Shugua) to wavy (Gunome, Notare) or those resembling cloves (Choji), each reflecting the smith’s signature and technique.

The Polishing: Revealing Hidden Beauty

Once forged and tempered, the blade passes into the hands of a specialized polisher (togishi), a process that can take months and is as crucial as the forging itself. Using a series of increasingly fine stones, the polisher not only sharpens the edge to an astonishing keenness but also reveals the intricate beauty of the blade, its hada (layer pattern), and the hamon. Polishing highlights the steel’s internal structure and the blade’s nuances, transforming a piece of metal into a work of art. The final result is a sword with an edge “hard as diamond” and an elastic body, capable of making precise cuts and withstanding impacts without breaking.

Caring for the Steel Soul: Maintenance and Peculiarities

A Japanese sword is a living work of art that requires specific care to maintain its splendor and functionality over the centuries. Proper maintenance is essential to preserve its historical and artistic value.

Protection Against Oxidation

The carbon steel of a katana is susceptible to oxidation, especially in humid climates. Traditionally, the blade is removed from the handle (koshirae), carefully cleaned with a special polishing powder (uchiko) to remove any oil or dirt residue, and then rubbed with rice paper moistened in Choji oil (clove oil). This oil creates an essential protective layer that prevents corrosion. Today, some experts also recommend modern synthetic oils, such as Ballistol, for longer-lasting protection with less frequency. If the sword is used, it should be oiled again after each use to ensure its preservation.

Oxidation and Professional Polishing

If a blade is not properly maintained, oxidation spots may appear. Reddish ones are “active” and dangerous, as they can irreparably damage the blade if not treated in time. Black spots are “fixed,” less dangerous, and can often be left, as they are a form of patina. To remove oxidation and restore the edge, professional polishing is required, a delicate task that only experts (togishi) should perform, as improper polishing can irreversibly degrade the blade and its value.

The Aging of the Blade

Over time and with multiple polishings, the outer layers of the blade are removed, which can lighten the sword and affect its original characteristics. A katana that has been polished many times and begins to show the soft steel of its core (shingane) through the hard outer layers (kawagane) is considered “tired” (tsukare). Sharpening or blunting them incorrectly can irreversibly damage them. Some forging schools had such a thin kawagane that shingane marks were common even in ancient examples, sometimes being a distinctive feature rather than just a sign of aging or wear.

The Untouchable Tang (Nakago)

A golden rule in katana maintenance is never to polish or scrape the tang (nakago), the part of the blade that goes inside the handle. Even if it rusts, this oxidation is a key factor, along with other parameters such as shape, file type, and inscriptions (mei), for dating and authenticating the sword. Polishing the nakago can halve the original value of a katana, as crucial historical information is lost. Only a thin layer of oil can be applied to protect it.

Beyond Steel: The Immutable Cultural Legacy

The Japanese sword, from its ritual origins to its current form as a work of art and collectible, is much more than a weapon. It is a symbol of honor, tradition, mastery, and the deep connection between the warrior and their spirit. It has survived bans, world wars, and relentless modernization, remaining relevant through centuries of Japanese history.

Thanks to the dedication of organizations such as the NBTHK (Japanese Society for the Preservation of Sword Art) and strict government regulations, the millennia-old art of sword forging is still alive, ensuring that each nihontō is not only a piece of history but a window into the indomitable spirit of Japan. Global admiration for these swords endures, recognizing their value not only for their artistic and economic beauty but also for the properties that made them so formidable and effective on the battlefield, and for the cultural legacy they represent.

If this fascinating journey through the world of Japanese swords has sparked your interest, we invite you to explore our collection.

At Medieval Shop, you will find a wide selection of Japanese swords, from historical replicas of katanas and wakizashis to maintenance accessories, perfect for collectors, martial arts practitioners, or simply for those who appreciate the beauty and history of these legendary pieces of steel. Discover the one that best suits your warrior spirit!