What connects a steel blade forged for dueling and a plant growing on the slopes of Oaxaca? The term espadín encompasses two worlds: that of the light sword that dominated duels and that of an agave that gave identity to one of the most consumed mezcals. In this article, you will explore both meanings with historical rigor, combat technique, botany, and the cultural mark they both left on weapons and palates.

The Hook: A Blade that Speaks of Speed and Precision

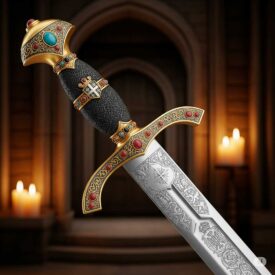

Imagine a candlelit room, two opponents bound by honor, and in their hands a tool of decision: the espadín. It’s not a sword for cutting logs; it’s an instrument of quick thrusts, surgical precision, and footwork. That same image of blade and form inspired those who named the agave with leaves similar to small swords, the botanical espadín.

What is the Espadín (White Weapon)

The espadín, as defined in the 17th and 18th centuries, is a light, rigid sword due to its triangular cross-section, with a blade length usually ranging between 1.09 and 1.14 m and an approximate weight of 750 g. Its main mission was the thrust: to quickly enter and exit, evade the rival’s attack, and end the duel. This specialization makes it a key piece to understand the evolution of civil white weapons and future sport fencing.

Design and Anatomy

The triangular section blade provides torsional rigidity: it is flat on two sides with a defined spine and apex. This geometry allows the force of the thrust to be transmitted directly to the point without significant deformation, something indispensable in a confrontation where every centimeter counts. The hilt usually features side rings or separate shells that protect the hand without adding too much weight or complexity.

Technique and Use in Combat

The espadín demands a combat style based on quick footwork, control of the center of gravity, and precision at the point. The classic stance favors fencing movements: advance, retreat, invitation, and lunge. Unlike wider swords, it is not used for forceful cuts; its effectiveness lies in the deep thrust and the ability to dodge.

The Espadín in Culture and Uniform

In the 18th century, the espadín went from being a dueling weapon to a formal accessory. Gentlemen and officers wore it as part of their attire, sometimes more ornamental than functional. Different royal houses or military corps used precious metals on the hilts to denote rank and distinction.

The Family Tree: From the Rapier to the Foil and Modern Sword

The espadín emerged as an evolution of the French rapier, with a focus on lighter weapons. In turn, the espadín gave rise to training variants such as the foil, a decisive tool in the transition to modern fencing. The search for safety in sports practice led to modifications in points and geometries, eventually leading to the blunt-tipped fencing sword characteristic of competitions.

The Espadín and its Chronology

Below you will find a condensed chronology with milestones marking the evolution of the espadín as a weapon and a piece of uniform.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| Late 17th Century | |

| Late 17th Century | In France, a lighter sword, the espadín, was conceived, which would be widely disseminated in the following century. |

| 18th Century | |

| First half of the 18th Century | The espadín became widely used. The first blades were of the colichemarde type (wide in the first third and very narrowed in the rest); this style persisted until the first third of the 18th century. |

| With the arrival of Philip V (early 18th Century) | French fashion introduces the espadín to Spain, replacing the rapier in the attire of gentlemen. |

| 18th Century (civilian use) | The espadín is common in the civil attire of titles and urban classes (nobles, escuderos, honest citizens, Perpignan bourgeois). It is described by the Admiral as a “harmless and known skewer” common in the 18th century. |

| Throughout the 18th Century | Espadines did not differ in military purpose except for the metal of the hilts: silver for the Royal House, gold-plated metal by royal concession for the Navy, and iron for the Army. |

| Mid-18th Century | Military side swords evolve to be on par with courtly espadines. Examples with “primitive” ricasso are documented (one with the figure “1740”). |

| Second half of the 18th Century | The use of espadines with “primitive” ricasso in military uniform becomes widespread. An Ordinance of 1785 prohibits luxury espadines and buckles for commanders and officers. |

| Late 18th Century | Towards the end of the century, espadines with ricasso predominated, although forms without ricasso, influenced by the “empire style,” began to generalize at the very end of the century, fully imposing themselves at the beginning of the 19th century. |

| Late 18th Century — Early 19th Century | |

| 1793 | During the reign of Charles IV, the Ordinances of 1793 already record gilded hilts on the swords of the Army and Navy. |

| 1803 | The 1803 Cavalry Regulation prescribes that cavalry officers will wear the espadín with a sleek black belt and steel hooks in “all other acts.” A more military gilded hilt design is approved; the definitive model for officers was pending approval. |

| 19th Century (Isabelline development and regulatory changes) | |

| 1833–1843 | After the Civil War and with the establishment of Isabel II’s effective government (personally in 1843), “Isabelline side swords” (espadines) appear for court acts and hand-kissing ceremonies. |

| 1840s | The espadín or “Isabelline” side sword emerges. Artillery Corps officers adopt the “Isabelline sword” with the 1843 model. |

| 1850s | The use of “Isabelline” swords alternates with suspension sabers; this practice persists until the early 20th century. The “Military Dictionary” (1863) describes the espadín as a common weapon among officers of mounted institutions and facultative corps outside of service acts. |

| January 30, 1867 | The use of the “Isabelline” sword for Infantry officers ceases with the approval of the Model 1867 side sword. |

| 1871 | An “Isabelline sword” appears in the tariff as “Side sword for Cavalry Officer, model 1851.” |

| May 16, 1887 | By Royal Order (C.L. nº204), cavalry chiefs and officers are authorized to wear the cross espadín they previously used, suggesting that its use may have suffered a temporary interruption. |

| 1889 | The 1867 model of Infantry Officer’s sword is replaced by a saber model. |

| 20th Century — recovery and contemporary use | |

| 1901 (September 14) | By Royal Order (C.L. nº219), the need for an espadín for infantry chiefs and officers is recognized, authorizing its voluntary use in certain non-military acts to replace the reglementary saber. Infantry officers recover the “Isabelline” espadín with a new model. |

| Early 20th Century | The use of the “Isabelline” sword in the Artillery Corps continued without interruption until the early 20th century. |

| Current Era and Legacy | |

| Current Era | The modern sport fencing sword derives from the espadín. The foil was created as a variant of the espadín and is now one of the three weapons of modern sport fencing. The espadín itself was not part of the three classic fencing weapons, but it was a popular 18th-century sword whose design influenced later practice and sport weapons. |

Blade, Balance, and Materials: Comparative Technical Anatomy

Here we summarize the essential characteristics of the espadín compared to other related weapons in a comparative table so you can quickly visualize its advantages and limitations.

| Type | Blade length (approx.) | Weight | Tactical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Espadín | 1.09–1.14 m | ~750 g | Fast thrusts, high maneuverability, not suitable for powerful cuts. |

| Rapier | 0.90–1.30 m | ~1 kg | Versatile: cuts and thrusts, variety of hilts. |

| Foil | 0.90–1.10 m | Light | Training and sport fencing; blunt tip for safety. |

| Fencing sword (modern épée) | ~1.10 m | Variable, designed for competition | Blunt tip, electrical scoring system, focused on thrusts. |

- Espadín

-

- Blade length: 1.09–1.14 m

- Weight: ~750 g

- Use: Duels and wearing; precise thrusts.

- Rapier

-

- Length: 0.90–1.30 m

- Use: Versatile, cuts and thrusts.

Ceremonial and Training Variants

In addition to the functional version for dueling, there are ceremonial examples used in solemn acts and training versions (foil). Ceremonial replicas prioritize aesthetics: engravings, gilded finishes, and elaborate scabbards, while functional replicas maintain geometries and tempering to be used safely in controlled practices.

Replica and Accessories

Fans of historical reenactment and classical fencing look for replicas that respect the proportions of the espadín: triangular section blade, balanced weight, and a hilt that allows for a secure grip. To preserve a functional replica, it is essential to know the steel’s temper and keep the blade free of corrosion with cleaning and protective oil.

The Espadín as a Symbol: From the Wardrobe to the Ceremony

Over time, the espadín gained a symbolic role in military and academic uniforms. It became a mark of rank and tradition, present in parades and ceremonies. Modern ceremonial versions are usually heavier and more ornate, adapted to protocol rather than real combat.

The Other Espadín: Agave Espadín and its Role in Mezcal

In a twist of natural language, espadín is also the common name for Agave angustifolia, a plant that grows in regions of Mexico and is the base of espadín mezcal. Its long, pointed leaves evoke the shape of a sword, hence the name. This agave is prized for its adaptability, productivity, and aromatic profile that adds complexity to the distillate.

Botany and Cultivation

The espadín agave is monocarpic: it flowers once and dies after fruiting. Its maturity cycle varies between 6 and 12 years depending on climatic conditions and agricultural practices. It is widely cultivated in Oaxaca (Sierra de Juárez), Guerrero, and Puebla. Its tolerance to poor soils and semi-arid climates makes it the natural choice for traditional mezcal production.

Organoleptic Characteristics of Espadín Mezcal

Mezcal made with espadín usually shows smoky and earthy notes complemented by fruity (pear, apple) and herbal (mint, spearmint) nuances. Its balance between final sweetness and slight bitterness makes it suitable for both solitary consumption and guided tastings where nuances by region and distillation process are explored.

Clarifying Doubts about the Espadín, the Rapier

What is the main difference between the espadín and the rapier?

The main difference between the espadín and the rapier lies in their hilt design and use: the rapier, which emerged in the 15th century, has a wider variety of hilts and is heavier (around 1 kg), with a blade of 90 to 130 cm oriented towards dynamic handling that combines thrusts and cuts; while the espadín, which appeared later in the 17th century, is characterized by having lateral rings or shells separate from the hilt and a lighter blade (around 750 g) of 1.09 to 1.14 m, designed primarily for quick thrusts and duels, being less suitable for cuts.

How did the name “espadín” originate for the agave?

The name “espadín” for the agave originated due to the shape of its leaves, which simulate a sword: they are long, narrow, and with thorny edges. This visual characteristic led to it being named this way, directly referring to the “sword” shape that its leaves present. Furthermore, its scientific name, Agave angustifolia, also alludes to its narrow leaves (“angusti” means narrow in Latin). Therefore, the term “espadín” reflects both the shape and the narrow and elongated proportion of its leaves.

What characteristics make the espadín ideal for duels?

The espadín is ideal for duels due to its lightness (around 750 g), rigidity conferred by its triangular section blade, and its length (between 1.09 and 1.14 m), which favors efficacy in thrusts. These characteristics allow great agility to dodge and attack quickly and precisely, although it is not suitable for cutting. Its design makes it excellent for agile handling and defense in direct combat, which made it a deadly weapon in duels. Furthermore, its rigid blade facilitates precise and controlled maneuvers, fundamental for dueling.

Care, Maintenance, and Preservation of a Functional Replica

To keep an espadín replica in good condition, it should be cleaned after use, any moisture removed, and a thin layer of protective oil applied. Avoiding strong impacts and storing it in a dry place prevents corrosion. In ceremonial replicas, cleaning focuses on preserving finishes and gilding.

Practical Reading: How to Interpret a Replica vs. a Historical Original

When comparing a replica with an original, it is key to review proportions, blade section, temper, and techniques for fastening the pommel and quillion. Modern replicas may use stainless or treated steels for greater resistance, while originals usually show repair, temper, and patina typical of use.

For Those Seeking to Understand the Espadín from Passion and Technique

The espadín offers a lesson on how function dictates form. Its design reveals an era where dueling was a social mechanism and prowess with the point was a valued skill. Similarly, the espadín agave reminds us that the word can travel from war to the field and take root in a gastronomic tradition.