The samurai (or bushi) were the members of the military class, the Japanese warriors. Samurai employed a range of weapons such as bows and arrows, spears and guns; but their most famous weapon and their symbol was the sword. Samurai were supposed to lead their lives according to the ethic code of bushido (“the way of the warrior”). Strongly Confucian in nature, Bushido stressed concepts such as loyalty to one’s master, self discipline and respectful, ethical behavior.

After a defeat, some samurai chose to commit ritual suicide (seppuku) by cutting their abdomen rather than being captured or dying a dishonorable death.

Below follows a short history of the Japanese warrior:

Heian Period (794-1185)

The samurai’s importance and influence grew during the Heian Period, when powerful landowners hired private warriors for the protection of their properties. Towards the end of the Heian Period, two military clans, the Minamoto and Taira, had grown so powerful that they sized control over the country and fought wars for supremacy against each other.

Kamakura Period (1192-1333)

In 1185, the Minamoto defeated the Taira, and Minamoto Yoritomo established a new military government in Kamakura in 1192. As shogun, the highest military officer, he became the ruler of Japan.

Muromachi Period (1333 – 1573)

During the chaotic Era of Warring States (sengoku jidai, 1467-1573), Japan consisted of dozens of independent states which were constantly fighting each other. Consequently, the demand for samurai was very high. Between the wars, many samurai were working on farms. Many of the famous samurai movies by Kurosawa take place during this era.

Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1573 – 1603)

When Toyotomi Hideyoshi reunited Japan, he started to introduce a rigid social caste system which was later completed by Tokugawa Ieyasu and his successors. Hideyoshi forced all samurai to decide between a life on the farm and a warrior life in castle towns. Furthermore, he forbade anyone but the samurai to arm themselves with a sword.

Edo Period (1603 – 1868)

According to the Edo Period’s official hierarchy of social castes, the samurai stood at the top, followed by the farmers, artisans and merchants. Furthermore, there were hierarchies within each caste. All samurai were forced to live in castle towns and received income from their lords in form of rice. Masterless samurai were called ronin and caused minor troubles during the early Edo Period.

With the fall of Osaka Castle in 1615, the Tokugawa’s last potential rival was eliminated, and relative peace prevailed in Japan for about 250 years. As a result, the importance of martial skills declined, and most samurai became bureaucrats, teachers or artists. In 1868, Japan’s feudal era came to an end, and the samurai class was abolished

Q: What is a Japanese sword anyway?

A: Japanese swords have a history of almost two thousand years. It is very difficult to sum up everything in a short paragraph.

Weapon making as a formal process is thought to have been introduced to Japan from China and Korea around 284 AD. Early swords tended to be straight but very few have survived Japan’s humid climate. Sword making was still primitive in nature during the 700s not taking on an advanced form until around the middle of the Heian Period (794-1191). The most famous Japanese smiths were active from around 900 to 1450. Like in other cultures Japanese swords developed to meet specific challenges on the battlefield.

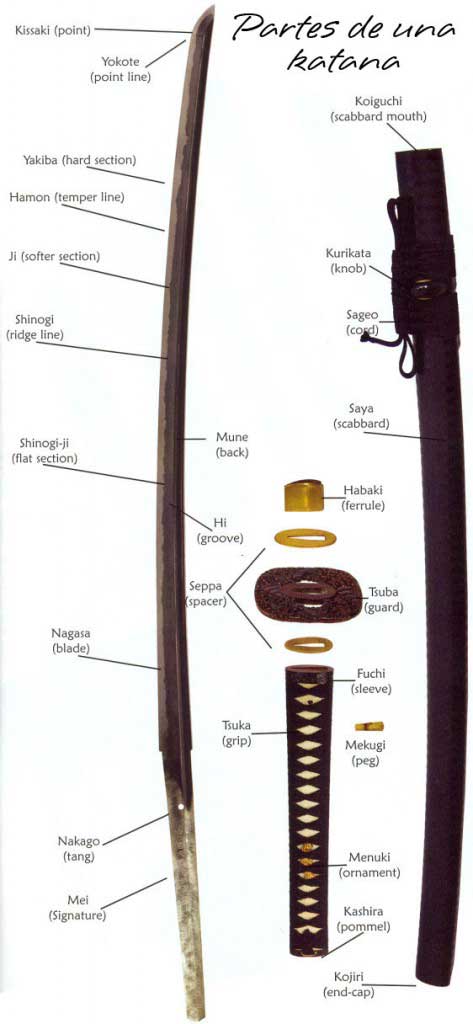

As we know them today, a Japanese sword is a curved, single edged, folded steel, tempered weapon coming in a variety of lengths. They were at various times worn slung below a belt, tucked through a sash (obi) often with a shorter sword, or suspended from a belt in modern military fashion. There are a myriad of technical terms varying by epoch, mounting of the blade, way it was carried, and technical specifications. Swords could be fit to an individual user and, with regular care, survive for hundreds of years.

Q: How is a Japanese sword made?

A: Historically, a swordsmith would refine raw materials from iron sand or iron ores – a laborious process. After about 1450, steel mills took over this process but like with most mass-produced items, quality suffered.

In short, several pieces of refined metal are heated, hammered together, pounded out (lengthened) and then folded – repeating the process many times. Slowly the metal will be worked into the shape of a sword. Each time the metal is folded the smith has to make sure no air or dirt is trapped in the weld, else the sword will break with use. Care in heating and working the metal must be taken to achieve the proper degree of hardness. Too hard and the sword becomes brittle, too soft and it will not hold and edge and will bend easily.

Blades come in a variety of cross-sections and compositions. Mono-steels swords were mainly made by mass production or with imported raw materials of high quality. Earlier or handmade swords might combine steels of various harnesses to improve overall quality.

A paste of clay and other materials is next spread over the blade and the whole sword heated to the proper temperature. It is then quenched in water, some modern smiths use oil, also of a proper temperature. Swords were not quenched in blood as some sources claim. The smith might then engrave his signature or other information on the tang (part under the handle) and pass the sword on to the polisher.

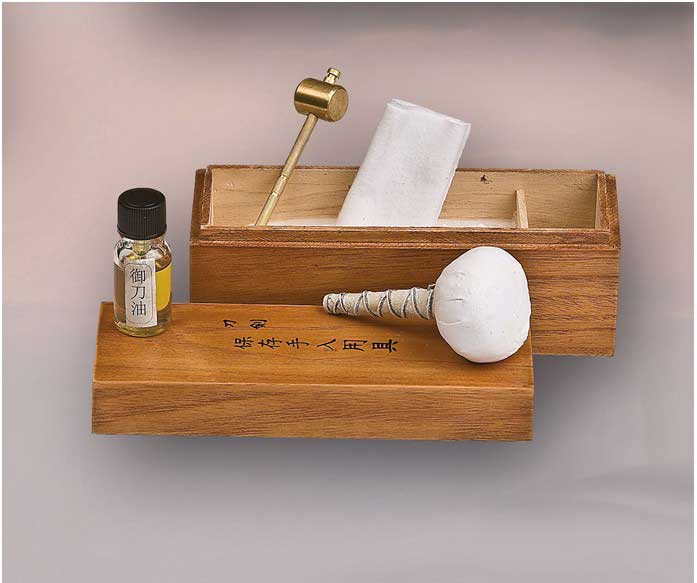

Polishing takes about one or two weeks of solid work to produce a fine finish and bring out the work of the original smith. It is an art and a skill all its own. Meanwhile still more artisans would have been making the other parts including the hilt ornaments, handle bindings and scabbard. Since WWII it should be noted that such specialization has been disappearing.

Q: Why is a Japanese sword curved?

A: The design probably got that way through trial and error. A lot about early sword making is lost. In a humid climate like Japan metal can corrode very quickly. As smiths started developing ideas brought from China and Korea, they began to settle on a single edged, curved design. The depth of this curve has changed over time. At one stage the bend was quite pronounced.

A curved blade is very good at cutting and Japanese sword styles either were based on, or changed to fit, this design. We need to remember that the Japanese sword developed to meet a very specific set of challenges. Over time, warriors and smiths decided that a curve worked best for them. Unlike in Europe, armor changed very little over the centuries, necessitating fairly few changes in sword design.

Q: I heard Japanese swords are folded something like a million times?

A: While Japanese swords might have thousands of layers, the process of folding was not often carried above 15 times. Most folded Japanese swords will have around 32,768 layers. Folding is where you take an ingot of metal, pound it out, and literally fold it back on itself, creating layers. This process is repeated again and again to draw out impurities in the original material and make a more uniform hunk of metal. Early Japanese smiths often used iron sand, a very poor raw material for making blades, and so the practice of folding greatly improved the finished blade.

Folding too much actually produces a weaker blade and makes it brittle. If a sword really could be folded a million times, the space between the layers of iron would be thinner than the iron atoms themselves. I think we all can see the problem with that.

Modern steel of high quality does not need to be folded to make a stronger blade as much of the impurities have been expunged during the smelting process. However, a modern smith might still fold the steel to adhere to tradition and to produce a grain-like effect in the finished, polished sword.

Lastly, Japan was not the only culture to fold and weld blades. Almost any culture with advance blacksmithing capabilities discovered how to remove impurities quite early on. Some of the Viking or famous Spanish methods for folding and welding were actually more advanced than Japanese methods. Folding does not, on its own, produce a stronger sword. It simply evens out overall composition and removes impurities.

Q: Do people still make Japanese swords in the traditional style?

A: Yes, there are many good smiths both in Japan and Spain. You can find a number of excellent non-Japanese smiths who can make a product of the same quality without too much trouble if you know where to look. The only difference will be where the sword is forged and who did the forging. Do a lot of asking around before you buy, and be ready to pay a few thousand dollars for a traditionally made sword.

Q: Is it true Japanese swords can cut through armor, metal and other swords?

A: A sword was never a warrior’s first choice when trying to break through armor. A spear, pike, or halberd (picture below, modified from Tenshaku) is much more capable of delivering much more force to a target than a sword. Also, many Japanese styles of sword combat taught to strike at the weakest points of a suit of armor – the joints and gaps – than try and push through a helmet or breastplate. Similar techniques were employed around the world. Swords of any culture were not effective armor piercing weapons. Don’t believe the hype.

If we look at Europe, armor was not fully discarded until a truly armor piercing weapon came around – the gun. If swords were so good at cutting through metal, wouldn’t heavy armor have gone out of fashion centuries before it did?

We are aware of a test published on the Internet where a sword master cut an antique helm to the depth of an inch or two. There are so many things wrong with the test it is hard to know where to begin. First, the helmet was not moving, as it would arguably be on someone’s head. The master was able to control for all other variables and the sword and helmet were not made in the same period.

It is hard to attest to the durability of a helmet against a sword made in a different era, possibly with different materials and different techniques. While impressive and a stunning testament to the maste’s skill, the cut probably would not have been fatal – maybe death would occur due to the blunt trauma, but not the cutting edge. Most warriors wore padding under a helmet or any armor, so a superficial gash of a few inches would not go very far into the person underneath.

Q: But I saw a picture of a Japanese sword sticking through a car door. What was up with that?

A: A screwdriver can be stuck through a car door and come out none the worse for wear. In fact it will do a better job than a sword. Car doors are not all that thick when it comes down to it. People rig these photos to look impressive. Please do not go around sticking swords into car doors and other objects. It is very dangerous.

Q: But Japanese swords are indestructible, right?

A: No sword is indestructible. A sword is only a hunk of metal shaped in a certain way. It posses no magical properties and imparts none to the user. In fact, Japanese swords are especially prone to bending. All swords take damage with use. These can be in the form of micro fissures or larger cracks. Eventually all swords undergoing prolonged use will fail. Abusing a sword will make it fail even faster. The edge-on-edge contact we see in the movies is an illusion. Edg- on-edge contact did occur in the heat of battle, but if you slam two bladed objects against one another, both blades will come away with at best nicks and gouges. Edge-on-edge contact was avoided at nearly all cost.

Q: So Japanese swords are lighter than European/others, right?

A: Not exclusively. The average weight for a Japanese sword was/is around 2 or 2.5 lbs. European swords may top off at around 5 lbs ~ 7 lbs for the big, two handed models like in the movie “Braveheart”, but often swords in the West were light as well. Warriors were sensible people and carrying around swords that are too heavy to use or exhaust the user would not be sensible.

Warfare in Europe was also under constant development. A weapon would be developed and armor would change to counter the new threat. Weapons would change to meet the challenge from the new armor and the cycle would continue. European swords were so diverse and covered such variety of design and function over the centuries that it is unfair to lump all of them together and say they were heavier and more cumbersome that the Japanese sword.

Q: Was the Japanese sword the best type of sword ever made?

A: Swords are tools. Some tools do a better job than others when put to a certain task. Japanese swords were very effective at cutting, as we mentioned earlier. The nature of armed combat in Japan helped to dictate the size, shape, and design of the sword, just as these factors did in other cultures. However, it is inaccurate to say the Japanese made the best swords the world has ever known. Used properly it was a very effective weapon. But removed from its proper context, like with most swords, efficiency may suffer. The proper tool for the proper job will always yield the best results.

Q: Who would win if they fought one another, a samurai or a European knight?

A: Speculation abounds and a few really good sites on the net offer wonderful articles. I encourage everyone to check them out. In short, all anyone can really say is that it ultimately comes down to the people wielding the swords and not any inherent advantage in style or weaponry.

Q: Is it true that some Japanese swords are so sharp they can cut a scarf just by laying it on the blades edge?

A: No, this is the stuff that dreams are made of. To make something really, really sharp, sharp enough to cut a falling piece of cloth via gravity alone, you have to make a sword that can do almost nothing else.

To reach extreme levels of sharpness you must make an edge that is very, very, very hard. With hardness comes brittleness. The edge would be so brittle it would shatter on contact with almost anything. Warriors from all ages were practical people. Their lives depended on the reliability and quality of their weapons. A sword sharp enough to cut a falling scarf would be very impractical. We always need to be careful of people trying to romanticize our view of Japan and its culture.

Q: The sword was the soul of the samurai, right?

A: In a sense, yes. There has been plenty written on the relationship between a samurai and his sword. I shall not go into that now. However, we need to keep in mind that a sword is like a pistol to the modern soldier – a weapon of last resort.

Samurai were often first trained in the use of the bow and horsemanship before progressing to use of the sword. In combat, arrows, spears, pikes, halberds, and polearms were most often employed before the sword. Both are much better at cutting through armor and keeping your opponent at a distance.

We also need to keep in mind the march of history and the media and what it has done to our perception of the samurai. Samurai themselves are guilty of fluffing up their image from time to time and Hollywood and even academia has fed the flames. I don’t want to go off on tangents, but this thread should get you off to a good start on the image distortion of what “samurai” means.

Q: I hear a lot about these Masamune and Muramasa swordsmiths. Who were they?

A: These two gentlemen warrant a thread all their own.

Q: What about these ninja swords I see around?

A: There was no such thing as straight bladed ninja swords. There are a product of Hollywood and the media. A sure way to spot that someone doesn’t know what they are doing is when they sell, or take photos with and claim to know how to use, “ninja swords”.

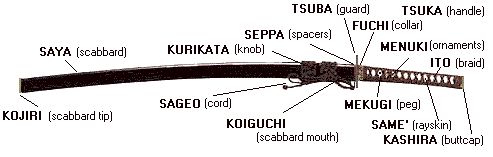

Parts of a Katana

Q: Where can I buy a Japanese sword?

A: There are many places to buy swords both online and through catalogues. However, the vast majority of swords easily available are intended to be hung on a wall and looked at, never sharpened nor put to use.

Phrases like “battle ready” are just sales tactics. There are plenty of good swords out on the market for practitioners of Japanese and Western martial arts that will stand up to responsible use. The key is to do a lot of research and ask around before you buy. Untrained use of a sword of poor quality, or abusing any sword, endangers yourself and others. Please watch this short video as an example. Please find a qualified teacher and seek professional assistance before buying a sword you intend to actually swing around.

Here you will find an aceptable sword with a strict control quality team, we do custom katanas but only for professionals, we beg you indentify yourselves if you are interested in this way.

Q: How do I know if the sword being sold on the Internet or in my local mall worth my money?

A: Research. Check out the Internet, visit forums where people who collect and use swords hang out, and talk with qualified instructors who can give you the latest advice. If you are just looking for a decorative item for the wall, just about anything that strikes your fancy and is in your budget will be worth your money. If you want a sword that will “do” something, be it trimming the hedges out back or for use in martial arts training, you will need to do some serious groundwork .We are a team are able to manufacture with excelent quality and afordable prices all swords you can imagine, …, speak with our sales dpt.

ABOUT ORIENTAL ARMOURS

The Samurai armor remains one of the most interesting and rare components of the Samurai era. The armor was constructed from bamboo, cloth and metal. Unlike its better known counterpart, the medieval armor, the Japanese example was much lighter, which provided for ease of movement but compromised protection.

The armor had to be light weight because the Samurai would often engage into hand to hand combat, requiring fast and precise movements. The majority of the armor was made from bamboo. The chest plate was usually one piece of metal while the arms and neck were composed of small pieces of metal tied together with colorful strings.

The Samurai warrior was an expert in hand to hand combat. The disciplines he mastered included Ju Jitsu, Iaido and swordsmanship. The Samurai would fight mounted on a horse or on foot. It is said that some of their opponents were strong and skilled enough to be able to punch through the Samurai armor with a single strike from their fist.