What do a padlock and a shackle tell us about power, trade, and justice in the Middle Ages? From ornate chests to damp dungeons, these objects were tools of protection and symbols of domination. In this article, you will discover their technical evolution, their functional variants, and the symbolic weight they carried through the centuries.

Padlocks and Shackles: Evolution from Antiquity to the Modern Era

The history of these locks and shackles is a chronicle of metallurgical ingenuity and social necessity. The following timeline summarizes the milestones that transformed a simple iron ring into complex designs and into artifacts of judicial and commercial control.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| Ancient Origins | |

| 500 B.C. – 300 A.D. | The existence of padlocks is documented from Roman times; the Romans knew padlocks (commercial influences with Asia and China). |

| First centuries of Christianity | Use of the sera (a type of padlock or movable lock) to protect domestic doors; sophisticated examples from Roman tombs are preserved in the British Museum. |

| 850 A.D. | Discovery in York (Viking settlement Jorvik) of padlocks with toothed spring mechanisms. |

| 850 A.D. – early 1000 A.D. | The name “candado” (from late Latin catenatum) was coined because it was used with a chain; initially designed to keep livestock in the meadow. |

| 1050 | The word cadnato appears in Castilian documents. |

| A century later (after 1050) | The term is already written as it is today in the Cantar de Mio Cid. |

| High and Full Middle Ages: Forging, Uses, and Forms | |

| 10th Century | Padlocks were also used to secure prisoners with handcuffs or shackles. |

| 11th – 12th Centuries | Refinement of iron technology; specialization of blacksmiths. Development of architectural ironwork and iron objects with economic and artistic importance (Romanesque). |

| 11th Century | Beginning of artistic ironwork in the Romanesque period. |

| 12th Century | Splendor of ironwork in the Romanesque period; from the 11th century, iron fittings applied to temple and fortress doors became widespread. |

| 1180 | The Fuero de San Sebastián (Sancho the Wise) refers to the “iron rights” (derechos del fierro). |

| Mid-13th Century | The Fuero de Teruel (in force until the end of the 16th century) records the “pressures” for males: prison, stocks, chain, garrots, handcuffs, tied hands and feet; women were only chained. |

| 13th Century | Formal survival of Romanesque ironwork. |

| Throughout the Middle Ages | Merchants promoted reliable locks to protect trunks, chests, and coffers; padlocks adopted their current shape, and large, artistically adorned padlocks became popular. The use of the pivot bolt became widespread instead of the horizontal pin, making picking more difficult despite still vulnerable mechanisms. |

| Late Middle Ages: Judicial Uses and Security Advances | |

| 1375-1425 (Murcia) | Murcia prison inventories record a wide variety of padlocks, keys, shackles, handcuffs, “arropeas” (restraints), and chains. |

| June 26, 1394 | Inventory of the Murcia prison: five shackles (one pair missing), handcuffs with their padlock (cadenado), two padlocks with their keys; it also mentions “Moorish keys” and other immobilization instruments. |

| 1456 (Aragon) | Inventory of Santa Olaria la Mayor castle documents two “grillyos” (shackles), an iron chain collar, and wooden stocks. |

| 15th Century | In Añón castle, “large shackles, three handcuffs, two slave chains” are recorded. |

| Mid-15th Century (Nuremberg) | Revolution in materials and mechanisms: iron-reinforced strongboxes, with complex gears capable of operating up to 24 bolts with a single key, surpassing the traditional “three-key chests.” |

| Transition to the Modern Period and Industrialization | |

| 19th Century | Secret and combination padlocks (keyless) appear, operating using a key of aligned letters. |

| Late 19th – early 20th Century | The forged padlock is replaced by cast padlocks. The presence of screws on a padlock places it in the 19th century (the universal nut was created in 1841), marking the transition to industrial production. |

How they were and how they were forged: materials, mechanisms, and decoration

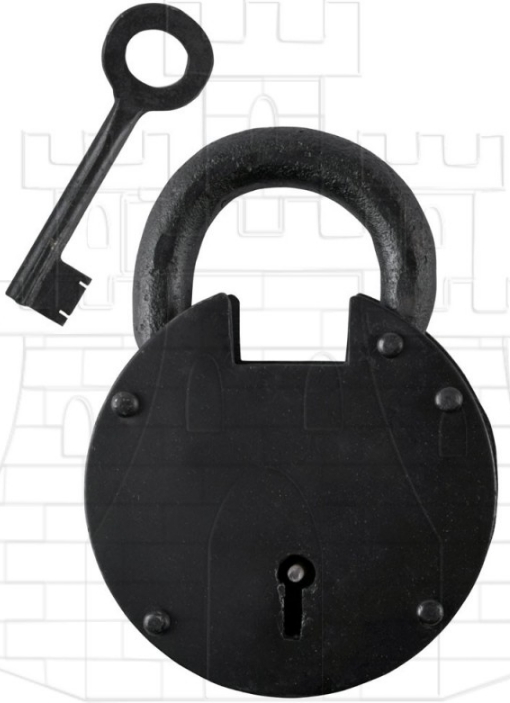

Medieval artisans worked iron and brass in forges where fire and hammer dictated the rhythm. Portable padlocks usually consisted of a metal body, a shackle, and a spring mechanism activated by a key.

Medieval artisans worked iron and brass in forges where fire and hammer dictated the rhythm. Portable padlocks usually consisted of a metal body, a shackle, and a spring mechanism activated by a key.

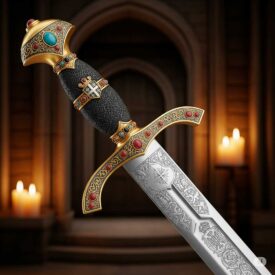

In addition to their function, many padlocks displayed engraved motifs: religious symbols, heraldic arms, or animal figures. In the hands of merchants, they became symbols of wealth and security.

Padlocks: functional design and ornamentation

The current form of padlocks consolidated in the Middle Ages: solid bodies, pivot bolts instead of horizontal pins, and keys with specific profiles. This made simple lock picking difficult, although it did not eliminate vulnerability to experienced blacksmiths.

Ceremonial or high-value padlocks could incorporate brass and small inlays; others, cruder, were purely utilitarian pieces for stables and chests.

Replicas and products inspired by medieval forging

Today, interest in historical reenactment and decoration revives ancient techniques and forms. Faithful replicas allow experiencing the aesthetics and mechanics of forging without sacrificing modern security.

Shackles: forms, types, and uses

Medieval shackles are as functional as they are ominous: iron rings joined by bolts and chains, designed to secure wrists, ankles, or the neck. Their technical simplicity made them robust and durable objects.

Below is a comparative guide to understand the most common variants recorded by historical and archaeological sources.

| Type | Main Use | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Chain Shackle | Standard wrist restraint | Two bracelets joined by a short chain; limited but practical mobility. |

| Hinged Shackle | Transfers and strict control | Hinged connections offering rigidity and a more secure closure. |

| Rigid Shackle | Maximum immobility for transport | No movement between rings; completely restricts mobility. |

| Oversized Shackle | Universal fit | Large rings to fit without squeezing; indicates control without intent to cause immediate harm. |

| Loop Shackle (modern) | Temporary and covert use | Materials such as nylon; lightweight and single-use; employed in discrete operations. |

- Chain Shackle

-

- Use: Standard wrist restraint.

- Characteristics: Two bracelets joined by a short chain; limited but practical mobility.

- Hinged Shackle

-

- Use: Transfers and strict control.

- Characteristics: Hinged connections offering rigidity and a more secure closure.

Judicial use, torture, and slavery: the harsher side of iron

Shackles were not just tools of containment; they were used in public punishments and torture methods. Hanging, immobilizing, and humiliating were practices that accompanied their use in pillories and dungeons.

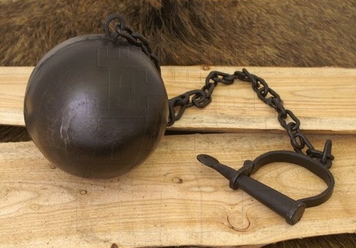

There were also leg shackles joined to heavy iron or lead balls, a recurring image in accounts and descriptions of prisons and forced transfers.

Construction, vulnerabilities, and legacy

Although robust, many medieval mechanisms were relatively simple and could be violated by experienced blacksmiths or thieves. Even so, their presence marked a boundary between the private and the public: security, punishment, and prestige.

Today these pieces are objects of study, reenactment, and aesthetic use. Modern replicas incorporate current materials and improved security measures to preserve the aesthetic without compromising contemporary functionality.

Clarifying doubts about medieval shackles

What were the most common materials for making medieval shackles?

The most common materials for making medieval shackles were primarily forged iron. This material guaranteed robustness and durability, which was essential for the control and security function of these devices. Although shackles could vary in design, forged iron was the standard due to its strength.

The most common materials for making medieval shackles were primarily forged iron. This material guaranteed robustness and durability, which was essential for the control and security function of these devices. Although shackles could vary in design, forged iron was the standard due to its strength.

How did medieval shackles differ from those used in other eras?

Medieval shackles differed from those used in other eras mainly due to their simple and robust design, consisting of a semicircular iron arc with two holes at the ends for a bolt secured with a cotter pin, allowing chains to be attached and placed on the neck, hands, or feet. This design was especially used as an instrument of torture and for the restraint of prisoners or slaves, being more rudimentary compared to later models that incorporated articulated hinges for greater limited mobility and security. Furthermore, medieval shackles had a strong symbolic component of degradation and oppression, while those used in more modern times were more standardized for police and penitentiary use.

What types of shackles existed for different body parts?

There are several types of shackles for different body parts, mainly designed for the hands or wrists, although some could be applied to other extremities. The main types are:

- Chain Shackle: Two metal bracelets joined by a short chain. These are the most common, used for standard arrests and basic wrist security.

- Hinged Shackle: The bracelets are joined with hinges (one or two), which adds rigidity and further restricts movement. Indicated for prisoner transfers.

- Rigid Shackle: Has no movement between the rings, offering the greatest immobility, especially useful for prisoner transport.

- Oversized Shackle: With larger rings to fit any wrist without squeezing, available in chain or hinged versions.

- Loop Shackle: Made of nylon, very flexible and light, single-use, used in covert operations or when discretion is required.

Additionally, there are special shackles made of specific materials (such as plastic alloys) that combine rigidity with lightness, some with multiple interlocking components for greater security.

Additionally, there are special shackles made of specific materials (such as plastic alloys) that combine rigidity with lightness, some with multiple interlocking components for greater security.

These types are primarily designed to secure the wrists, but in historical and less common contexts, shackles and restraints also existed for ankles or to secure other body parts, although those mentioned are the most common in police and security contexts.

What symbolism did shackles have in medieval culture?

In medieval culture, shackles primarily symbolized degradation and the loss of human dignity, representing oppression and the violation of the fundamental rights of subjected individuals. They were seen as physical tokens of slavery, punishment, and torture, recalling the condition of a prisoner, slave, or punished person, and the absolute limitation of individual freedom. They also alluded to moral and social condemnation, reflecting the humiliation and absolute control of power over the individual’s body and will.

In medieval culture, shackles primarily symbolized degradation and the loss of human dignity, representing oppression and the violation of the fundamental rights of subjected individuals. They were seen as physical tokens of slavery, punishment, and torture, recalling the condition of a prisoner, slave, or punished person, and the absolute limitation of individual freedom. They also alluded to moral and social condemnation, reflecting the humiliation and absolute control of power over the individual’s body and will.

How were shackles used in torture during the Middle Ages?

Shackles in torture during the Middle Ages were used to immobilize and cause prolonged pain to prisoners, generally tied at the wrists, ankles, or neck with these iron rings attached to chains fixed to walls or posts. Victims remained hanging or chained, which caused dislocations, cramps, intense pain, and over the long term could lead to limb invalidity. This practice sought to humiliate, punish, and physically weaken, being common in dungeons and as a method to publicly display the condemned. In some cases, shackles were also used in the pillory or to restrain slaves and convicts during transfer.

Along the lines of iron and forging, there are also stories of technique, trade, and crafts that preserved knowledge. If you are interested in delving into replicas, conservation methods, or mechanical evolution, this legacy offers much to explore. Medieval forging continues to speak: in padlocks and shackles, stories of protection, punishment, and aesthetics are read.