The saber, with its characteristic curved blade and single edge, is much more than a weapon; it is a witness to military history and an enduring symbol of honor and valor. Although colloquially often confused with the sword, the saber possesses a distinctive morphology that sets it apart. This curvature of the blade is, in fact, what fundamentally distinguishes it from the sword, providing greater speed in combat by allowing a clean cut that prevents the weapon’s blade from becoming embedded in the opponent’s body. Join us on a fascinating journey into the world of military sabers.

A Historical Look: From the Steppes to Parades

The history of the saber is a journey spanning cultures and continents, a testament to the evolution of warfare and cavalry. Its origins date back 10 centuries before its appearance in Western Europe, being first incorporated by the Mongols and Turkomans of Central Asia around the 9th century. These early forms of curved blades evolved on the vast Eurasian plains with nomadic equestrian peoples like the Scythians and Huns, who understood the tactical advantage of a blade designed for quick cutting from horseback. The curvature, which is generally located from the tip to the middle of the saber, generates a deep slash and aims to ensure that a man on horseback, when swinging the arm with this weapon, forms a wide circle over the infantryman, achieving that at the point of cut the saber is always tangential. For this reason, it does not stab, but cuts, thus increasing the wound without embedding the weapon.

The decisive influence for the spread of the saber came from the East. The light cavalry of Arabs and Turks, armed with curved blades (known as ‘scimitar‘ in the Arab world), proved to be extremely effective, rapidly spreading the saber across Asia and North Africa with the Islamic conquests. In fact, the influence of the Turco-Mongols can be traced in the development of all sabers, from the Dāo (Chinese) to the Shamshir (Persian), Tulwar (Indian), Kilij (Turkish) and, later, European sabers such as those of the hussars and those used by armies such as the French and American.

The adoption of the saber in Europe was gradual. In the 16th century, the Hungarian hussars, a light cavalry, began to use it, and their success led other European armies to adopt it. The Winged Hussars of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were particularly famous, feared by the Turks. During the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), the saber became the standard weapon of light cavalry, consolidating its position as the preferred choice for mounted units.

The Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) marked the zenith of cavalry as a decisive force on the battlefield. Sabers of this era, such as the famous French An XI model, were lighter and more balanced, allowing for faster and more precise blows. Throughout the 19th century, the saber fascinated the entire military establishment, also being used by infantry, with lighter and straighter sabers that were better suited to the parry and riposte fencing of the schools of the time. However, because of this, sabers designed for cavalry have a great curvature, being almost circular; while those designed for infantry have a lesser curvature, as importance must be given to the defensive function: keeping the enemy at bay and parrying their blows.

However, the 20th century brought the end of classical cavalry. The appearance of firearms such as machine guns and barbed wire made cavalry charges almost impossible. Although it had a brief resurgence in the first months of World War I, with the transition to trench warfare, the saber disappeared from the main battle lines. In the United States, for example, the saber was discontinued as a weapon for cavalry use in 1934, with mounted units making their last appearance in force in 1940-41.

Currently, the saber has retained its place primarily as a ceremonial weapon, displayed in military parades and other official occasions. It is an indispensable dress element in the uniforms of Army personnel, both land, air and sea, symbolizing the tradition and honor of the armed forces.

Anatomy and Technical Evolution of the Saber

The design of the saber has been meticulously adapted to optimize its function, especially in combat on horseback, where every detail of its anatomy contributed to its effectiveness.

The Blade: The Heart of the Saber

The main feature of the saber is its single curved edge and a blunt false edge. The triangular shape of its blade improves its cutting power, although it worsens its thrust. Highly curved blades were excellent for powerful blows, taking advantage of the momentum of the rider and horse, while those with more moderate curvature, common in European cavalry sabers, sought a balance between cutting and thrust, offering greater versatility. The blade length for cavalry sabers usually ranged between 80 and 90 centimeters, an ideal size for reach from horseback.

Hilt and Guard: Protection and Control

The hilt had to guarantee a secure grip, even at a gallop, under intense combat conditions. Many had a slight curve to ergonomically fit the rider’s hand, providing optimal control. The guard, often basket-shaped or stirrup-shaped, was essential to protect the rider’s hand from opponent’s blows. An interesting detail in some designs is the thumb notch on the quillon, which allowed for more precise handling and greater control of the blade, facilitating quick and decisive movements. It is important to note that angled or ‘pistol grip’ hilt styles never completely disappeared and continued to be used in some types of sabers throughout history, demonstrating their effectiveness and preference in certain military traditions.

Materials and Manufacturing: The Master Blacksmith’s Skill

The quality of the saber largely depended on the materials used and the exceptional skill of the blacksmith. The best blades were forged from Damascus steel, known for its distinctive patterns and strength, or, later, with high-quality carbon steel. These materials allowed for an optimal combination of hardness at the edge, crucial for maintaining cutting ability, and flexibility at the spine, essential to prevent breakage under combat stress. Hilts were commonly made of wood, covered with leather or wire for a firm and durable grip, while officers’ sabers could incorporate more precious and decorative materials such as ivory or mother-of-pearl, reflecting their status. Scabbards evolved from simpler materials like leather with iron mounts to polished iron or “japanned black” scabbards, which offered greater durability and blade protection.

Practical Use and Combat Tactics

The saber was the quintessential weapon of cavalry, and its tactical use required great skill and rigorous training. The effectiveness of the saber on the battlefield depended not only on its design, but on the rider’s mastery in employing it in the heat of battle.

Equestrian Combat Techniques

Equestrian tactics were based primarily on powerful blows executed at a gallop, taking advantage of the horse’s momentum to exponentially increase the force of impact. Typical blows were directed at the opponent’s head, shoulders, or torso, seeking to quickly incapacitate them. A common and devastating technique was the “mill cut,” where the rider swung the saber in a circular motion over their head to strike with full force in massive attacks, creating a danger zone around the rider.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Curved Saber

The curved design of the saber offered significant advantages in mounted combat:

- Greater cutting effect: The curvature amplified the cutting capacity, allowing the edge to slide through the target with greater efficiency, causing wider and deeper wounds.

- Better control: Its shape facilitated the guiding of the blade, especially at a gallop, where precision was crucial. The curvature helped keep the saber on the desired trajectory.

- Lower risk of jamming: The curvature reduced the possibility of the blade getting caught in the opponent’s body or equipment, allowing the rider to quickly retrieve the weapon for the next blow.

Despite its advantages, the saber also presented certain disadvantages: it offered less thrusting power compared to straight blades, making it less effective for piercing armor or for point-to-point combat. In addition, it was less versatile in narrow terrain or in close-quarters combat on foot, where a straight sword could offer greater agility and precision in the thrust.

Complementary Weapons

Although the saber was the primary weapon of the cavalry, it was usually combined with others to maximize effectiveness in different phases of combat. At the start of an attack, pistols were often used to break enemy formations or cause casualties at a distance, followed by a transition to saber combat once the cavalry engaged in close contact. Later, with the advance of weaponry technology, carbines were added for greater range and firepower, allowing cavalry to operate more flexibly on the battlefield.

The Diversity of Sabers: Variations and Traditions

The military saber was not a uniform instrument; its design reflected specific military needs and the rich national and cultural traditions of each region. This diversity is a testament to the weapon’s adaptability to different combat styles and aesthetic preferences.

Light vs. Heavy Cavalry: Designs for Specific Functions

- Light Cavalry Sabers: Used by units such as hussars and uhlans, these sabers were lighter, with more curved and narrower blades. Their design was optimized for speed, reconnaissance, and quick attacks, allowing riders to maneuver with agility and strike effectively without sacrificing speed.

- Heavy Cavalry Sabers: Employed by units such as cuirassiers and dragoons, these sabers were wider and heavier, with less curvature. Their design focused on strength and penetration power, making them ideal for breaking enemy lines and engaging infantry or heavy cavalry with a forceful impact.

Cultural and National Influences: A Mosaic of Designs

French elegance was reflected in sabers such as the Model 1822, which combined aesthetic beauty with practical functionality, becoming an icon of military design. Prussian functionality manifested itself in the pallasch, a type of straight-bladed saber, known for its penetration power and robust design, closer to a heavy sword.

The Polish-Lithuanian Karabela saber is a fascinating example of cultural fusion, combining Eastern and Western elements in its design, and was also used in Ottoman and Persian lands, demonstrating the interconnectedness of military traditions. The Langes Messer (long knife in German) was a sword-like object with a knife hilt and a characteristic nagel (a protrusion on the guard to protect the knuckles), initially popular among peasants, but adopted by higher social classes and even emperors. It was particularly prevalent in Eastern Europe, despite its German name, with examples found in Malbork (Poland).

Japanese katanas are, in their Westernized form, considered Japanese sabers due to their curved single-edged blade, although their development and philosophy of use are unique. Japanese Imperial military swords, known as Guntō, represented a significant field in the history of the Japanese sword due to their quantity and organization, although they were often overlooked because of their involvement in the war. In Ethiopia, the Gurade typically uses imported European blades with local Ethiopian hilts, considered distinct sabers from the shotel, a curved double-edged sword.

North African Nimchas (Moroccan, Algerian, Omani/Zanzibari) could have straight blades, often from old European rapiers or broadswords, demonstrating the reuse and adaptation of existing blades into new saber configurations. The term “scimitar” is a transliteration of the Persian shamshir and was used in the 16th century to define all foreign curved swords, regardless of their local name or origin. Native terms such as saif (Arabic), gươm, kiếm, đao (Vietnamese), Tulwar (Indian), Shamshir (Persian), Kilij (Turkish), Spada, Spadone (Italian) are often simply translated as “sword” or “saber” in English, which shows that detailed classifications are more of a modern and academic phenomenon.

US Cavalry sabers in the Revolutionary period were diverse, some straight and some curved, with a typical blade length of 32 to 37 inches. Contracts with manufacturers like N. Starr and William Rose produced thousands of sabers, evolving in blade and hilt design and materials to meet the needs of a growing army. The Patton Saber or Model 1913, designed by the famous General George S. Patton, was double-edged and straight-bladed, and was not designed to be carried personally due to its weight, being more a combat tool than a personal weapon.

There are numerous models of Spanish military sabers throughout the centuries, from the 18th to the 21st century, for various branches such as Hussars, Dragoons, Infantry, Artillery, Engineers, Civil Guard, and the Royal Guard, both for troops and officers, and also boarding sabers for the Navy, reflecting the rich military history of Spain.

The Saber in Modern Fencing

Beyond its historical role on the battlefield, the saber has found a prominent place in the sport of modern fencing. Currently, the saber is, along with the épée and foil, one of the three main fencing weapons, each with its own rules and distinctive characteristics.

The modern fencing saber has a cup-shaped guard that protects the fencer’s hand. The total length of the fencing saber is 90 cm and its maximum weight is 500 grams, making it a light and manageable weapon, ideal for the speed and agility that characterize saber bouts. Touches or points can be scored by thrusting with the tip or, uniquely in saber fencing, by making a cut with the edge of the blade. The valid target area is the entire body from the waist up, including the head and arms, which expands the possibilities for attack and defense. Saber bouts are known for being the fastest and most agile in fencing, requiring excellent physical fitness, quick reflexes, and a constant offensive strategy from competitors.

The Saber in Culture and Symbolism

The saber transcended its function as a weapon to become an important symbol of status, honor, and military tradition, permeating culture and art throughout the centuries.

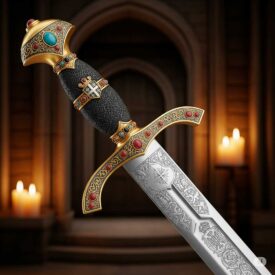

Object of Status and Distinction

For officers, the saber was an indispensable attribute that reflected their rank and social position. It was not just a combat tool, but an extension of their authority and prestige. Parade sabers, richly decorated with intricate engravings, precious metals, and ornate hilts, were common, serving as insignia of honor in formal ceremonies and events. The quality and design of an officer’s saber often indicated their position within the military hierarchy.

The Saber in Art and Literature

The saber has symbolized chivalry, courage, adventure, and nobility in countless works of art and literature. From historical paintings that immortalize cavalry charges to epic poems that glorify bravery on the battlefield, the saber is a recurring figure. A notable example is Theodor Körner’s poem “Song of the Sword,” which personifies the weapon as a faithful companion to the soldier, a symbol of their duty and destiny, imbuing the saber with a soul of its own.

Modern Ceremonial Use and Legacy

Today, the saber is used in military parades, officer promotion ceremonies, and other official occasions, keeping its rich tradition alive. A touching example is the “saber arch” at military weddings, where an arch of sabers is formed by the couple’s comrades in arms, symbolizing the bond with the military community and the protection offered to the new couple. This ritual underscores the saber’s continuing relevance as an emblem of honor and camaraderie.

Interestingly, the saber is also used in the traditional Egyptian martial belly dance, known as “El Ard,” which is performed by men who carry the sabers vertically, ready to fight, while dancing. Raks al Sayf, another form of dance, involves balancing the object on the head, hip, stomach, shoulders, etc., demonstrating the cultural versatility of the saber beyond its military function.

Preservation and Resurgence of Interest

The saber is very popular among collectors and military history enthusiasts. Museums worldwide exhibit impressive collections that document its evolution through centuries and cultures. Furthermore, interest in historical martial arts has grown significantly, with clubs and groups dedicated to studying and practicing saber fencing, helping to preserve knowledge of its use and ancient combat techniques. This resurgence ensures that the saber’s legacy continues to be studied and appreciated by future generations.

The military saber is a tangible link between the past and the present, reminding us of values such as honor, courage, and leadership. Its history teaches us about the evolution of warfare and the importance of adaptability and innovation over time. From the steppes of Central Asia to the Napoleonic battlefields and today’s ceremonial parades, the saber has proven to be a formidable weapon and an enduring symbol. Its legacy continues to inspire and fascinate those who appreciate the history, technique, and symbolism of these magnificent curved blades.