Why does the image of the scimitar dominate our imagination?

Imagine the desert plain at dawn, the rustle of leather, the gleam of a curved blade reflecting the first light. That image — so often repeated in stories, films, and flags — summarizes the fascination surrounding Muslim swords. But the real history is more complex, diverse, and technical than any stereotype suggests.

In this article you will learn: how swords evolved in the Islamic world, what types dominated different regions, why Damascus steel and wootz made a decisive difference, and how to choose or recognize historical replicas with discernment. All told with historical rigor and a narrative tone that transports you to the blacksmith’s forge.

From Straight Blade to Curved Saber: Evolution of Swords in the Muslim World

The transition from straight-bladed swords to curved sabers was neither instantaneous nor homogenous. It varied according to regions, nomadic influences, and tactical needs. Below is a summarized chronology with the key milestones in that evolution.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| Pre-Islamic Period and Early Islamic Times (up to the 7th Century AD) | |

| Straight-bladed swords | Predominance of straight-bladed swords among pre-Islamic Arabs and in the time of Prophet Muhammad; it is not the period of the curved saber. |

| Preserved swords | Several straight Arab swords in the Topkapi Palace Museum (Istanbul), including one attributed to the Prophet’s father-in-law, dated to the 6th century; curved or straight quillons similar to European ones. |

| Production centers | Yemen noted for manufacturing and poetic reputation; Kufa and Basra recognized for the strength of their steel. |

| Shamsaám Swords | Pre-Islamic type identified by two holes at the end of the blade. |

| Umayyad and Early Abbasid Period (7th – 9th Centuries AD) | |

| Persistence of the straight blade | Documented by textual sources, material findings, and representations in sculptures and coins from the Umayyad period (8th century). |

| Swords of caliphs | Preservation of swords attributed to early caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, Ali); some transmitted between rulers (e.g., to Muʿawiya and then to Harun al-Rashid). |

| Introduction of the saber | Probable introduction of the saber by Turkic warriors from Central Asia employed as royal bodyguards during the Abbasid caliphate of al-Muʿtasim (833–842). |

| Oldest preserved Islamic saber | Oldest Islamic saber found in Nishapur (Iran), indicative of use in an Islamic context in the 9th century. |

| Artistic representations | Mural paintings from Nishapur (9th century) show warriors with short curved sabers and long straight swords; a painted shield from Mount Mugh near Samarkand (ca. 722) also indicates use of sabers from the 8th century. |

| Origin of the shamshir | The shamshir originated in Persia and Central Asia around the 9th century, initiating the family of Persian curved sabers. |

| Change in carrying style | The Abbasid caliph al-Mutawakkil (847–861) consciously abandoned the baldric in favor of the saber and belt. |

| Medieval Islamic Period (10th – 15th Centuries AD) | |

| Al-Andalus: straight blades | In Al-Andalus, straight-bladed swords continued to be used; Hispano-Muslim swords (12th–13th centuries) feature a spherical pommel and short curved quillons. |

| The Jineta | Nasrid straight-bladed sword, double-edged and grooved to the middle, bone-shaped hilt and round pommel; manufactured in Toledo between the 14th–15th centuries. |

| The Scimitar | Western term for curved sabers spread from India to the Maghreb in the Middle Ages; scimitar manufacturing consolidated in Persia around the 13th century (e.g., shamshir, kilij). |

| The falchion | Short, curved saber (name from Ar. al-janbīyah/al-janbār), widely used in the Iberian Peninsula, the Mediterranean, and Italy from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. |

| The Crusades (1095–1270) | Muslims in the Crusades mostly used straight swords; during this period, the reputation of Damascus swords (Dimiski) grew. |

| Mamluk period | The saber was the preferred weapon of the warrior elite; in parallel, finely decorated swords were used in ceremonies (e.g., “saif badawī” or Bedouin sword) in sultanic investitures. |

| Re-adoption of the baldric | Rulers such as Nur al-Dīn (1146–1174) and Saladin (1138–1193) re-adopted carrying the sword from a baldric for reasons of traditionalist piety. |

| Late Ottoman Period and Modern Age (16th – 19th Centuries AD) | |

| The Yatagan | Characteristic sword of the Ottoman Empire, widely used between the 16th–19th centuries. |

| The Karabela | Of Ottoman origin, used by Janissaries and Sipahis in the 17th–18th centuries; adopted by Europeans (especially Poles) in later centuries. |

| The Mamluk sword | Design with subtle curvature, typical of Turkic-Islamic culture; gifted to Americans in the 19th century and used as a ceremonial sword by U.S. naval officers. |

| Perceptions in the West | In the 19th century, images of the Prophet with sword and Quran proliferated, and the myth of Islamic expansion “by the sword” persisted, popularized since the Crusades and reinforced in European narratives. |

| Beyond Chronology: Relevant Sword Types | |

| Kilij | Distinctive Turkish sword, with a blade that combines curve and reinforced point (yelman), inheriting Hunnic traditions; powerful cutting ability. |

| Agir Kilij | Turkic variant from Central Asia with a heavy blade and great cutting power, surrounded by legend for its lethality. |

| Gaddare | Short, extremely sharp and heavy Turkish sword; controlled with two cables in some examples for special use. |

| Pala | Turkish sword shorter and wider than the yatagan, used by naval and cavalry forces. |

| Daga | Typical Close-combat dagger among ancient Turks (35–40 cm), often richly decorated and fundamental in close combat. |

| Kabila | Hybrid with a jineta-type hilt and curved scimitar blade; similar to a gumia but longer. |

Origins and Forging: From Indian Wootz to Damascus Steel

The “swords of Damascus” are often spoken of as almost mythical weapons. Behind the legend was a real technique: the use of wootz steel (produced in India) and its subsequent treatment in Persian and Syrian workshops.

What made these blades superior pieces? A high carbon content (1.5–2.0% in many cases) combined with folding and forging processes that distributed hard and flexible microstructures in the blade. The wavy pattern, visible on many blades, was the hallmark of the smith’s work and an indicator of quality.

Techniques and Myths

Artisans controlled temperature and times for pickling, hardening, and tempering. The result was a blade capable of withstanding impacts without breaking and maintaining a sharp edge for longer. Some exaggerated stories said these blades could cut a chain or a piece of silk; the real truth is that they combined hardness, elasticity, and beauty.

Key Typologies: A Map of Forms and Uses

The term “Muslim swords” groups many forms that respond to local traditions. Below is a comparative table that will help you distinguish them at a glance.

| Type | Origin | Curvature | Use | Outstanding Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kilij | Turkey / Central Asia | Pronounced curvature with yelman (reinforcement at the end) | Powerful cutting on horseback and close combat | Reinforced tip that concentrates the force of the blow |

| Shamshir | Persia | Fine and elegant curve | Long, fast cuts from horseback | Thin blade sharpened towards the tip |

| Yatagan | Ottoman Empire | Moderate curve, wide blade | Infantry and personal guard | Distinctive hilt without pronounced guard |

| Scimitar / Falchion | Broad: Persia, India, Maghreb, Al-Andalus | Variable curvature, often marked | Cavalry and striking/cutting fights | Versatility; sometimes combine edge and false edge |

| Jineta | Al-Andalus (Nasrids) | Mainly straight | Combat and ceremony | Double-edged blade with groove to the middle |

| Dimiski (Damascus) | Syria / various forges | Straight or slightly curved depending on model | High edge quality and renown | Visible pattern on the blade (Damascus) |

- Kilij

-

- Origin: Turkey and Central Asia.

- Use: striking and cutting, ideal on horseback.

- Distinguishing feature: yelman at the tip providing additional force.

- Shamshir

-

- Origin: Persia.

- Use: long, fast cuts.

- Distinguishing feature: elegant curvature and thin blade.

Forms, Hilt, and Symbolism

Hilts reveal much: a rounded pommel, a simple guard, or ornate quillons provide clues about the sword’s origin and function. In many pieces, the decoration is not only aesthetic: inscriptions, Koranic verses, or protective formulas were engraved to confer meanings of legitimacy, protection, and status.

The crescent moon, vegetal motifs, and calligraphy frequently appear on hilts and scabbards. These details articulate social and religious identity, while also elevating the sword to an object of prestige.

The Sword as Symbol

In the Islamic imagination, the sword represents justice, authority, and duty. Its use was regulated by ethical codes and combat norms; historical accounts emphasize prohibitions such as deliberate mutilation or attacking civilians, reflecting an ethics of war that sought to limit barbarity.

How to Read a Historical Replica: Details That Matter

If you are looking for a replica, pay attention to the blade geometry, steel type, finish, and hilt ergonomics. A well-made replica looks to history: balanced proportions, proper tempering, and materials consistent with the original.

Practical tips:

- Balance: test the balance point; a cavalry sword usually has it closer to the guard.

- Curvature: determines cutting effectiveness and handling type.

- Blade: observe the Damascus pattern and construction (forged steel vs. stamped steel).

Replicas and Reproductions: Choosing Wisely

When a replica respects proportions and uses appropriate steel, it can be both a collector’s item and a didactic tool. Differentiate between decorative and functional items; for real use, technical specifications must be clear.

Next, some recommendations on what to value when comparing similar pieces.

| Attribute | Decorative | Functional / Replica |

|---|---|---|

| Blade material | Low alloy steel or plated | Carbon steel or good quality stainless steel, controlled temper |

| Construction | Assembled and glued parts | Forged and heat-treated, functional rivets |

| Aesthetic detail | Surface decoration | Authentic engravings, inlays, and historical verification |

Emblematic Examples and Their Context

Exploring specific pieces helps to understand the range: the Nasrid jineta shows the persistence of the straight blade in Al-Andalus; the shamshir illustrates the Persian imprint on the curved design; the kilij represents the Turkic influence and its adaptation for horseback combat.

The Jineta and the Kabila

The jineta is distinguished by its bone-shaped hilt and central fuller. It was a practical and elegant sword, used both in combat and at court and ceremony. The kabila, a hybrid, shows the creativity of artisans in combining elements from different traditions.

Tactics and Ergonomics: Why Form Matters

Curvature affects the contact angle and the transition of the cut. In a cavalry charge, a curved blade maintains momentum and prevents the tip from getting stuck in the opponent’s body. In infantry, straight blades favor thrusting and versatility.

Blacksmiths and warriors designed each sword to respond to an environment: terrain, type of enemy, armor, and combat customs. This regional adaptation explains the diversity we observe.

Historical Cases

Figures like Saladin are remembered not only for political strategy but also for the symbolic choice of their weapons. Chronicles highlight the preference for quality blades and the ceremonial carrying of swords in Mamluk sultanates.

Preserving and Valuing a Historical Sword or Replica

Proper maintenance preserves both aesthetics and structural integrity. Avoid humidity, perform gentle cleanings, and protect from impacts. For functional replicas, a protective oil and periodic temper checks are essential.

A piece with history also requires documentation: provenance, techniques used, and, if possible, steel analysis. This increases its historical value and significance.

Legacy and Cultural Significance

Muslim swords are much more than weapons. They are signs of identity, power, and aesthetics. Their forms and decorations tell stories of cultural contact: from India to Al-Andalus, from the workshops of Damascus to the forges of Toledo. Understanding them is to glimpse a map of exchanges, battles, and masterful craftsmanship.

Muslim swords are much more than weapons. They are signs of identity, power, and aesthetics. Their forms and decorations tell stories of cultural contact: from India to Al-Andalus, from the workshops of Damascus to the forges of Toledo. Understanding them is to glimpse a map of exchanges, battles, and masterful craftsmanship.

Today, when you contemplate a replica, think about the chain of knowledge that made it possible: tiny carbon grains, hammer blows, expert hands, and a long historical journey.

If anything is clear, it’s that there is no single “Muslim sword”: there is a constellation of forms, functions, and meanings that cross centuries and geographies. This diversity is what fuels both academic research and the passion of collectors and re-enactors.

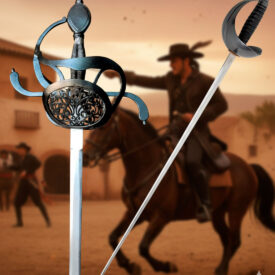

ALFANJES | CIMITARRAS | JINETAS | KABILAS