The falcata is one of the most emblematic weapons of Antiquity in the Iberian Peninsula: a curved sword, heavy towards the tip and with a visual presence that makes it unmistakable. Its fame as a lethal weapon and its rich ornamentation in some specimens have made it an object of study, admiration, and reproduction by collectors and enthusiasts. In this article, we review its history, design, manufacturing, combat use, and its survival as a cultural symbol.

What exactly is a falcata and why is it so impressive?

The word immediately evokes the image of a curved, thick blade that concentrates mass in the final third to produce devastating cuts. Broadly speaking, the falcata is a single-edged sword—though with a false edge on the back near the tip—asymmetrical and with a slight curvature that facilitates both cutting and thrusting. Its usual length places it below 55 cm, classifying it as a short infantry sword and making it especially useful in close combat.

Design and ergonomics: the key to its effectiveness

The blade of the falcata is wider towards the tip, which turns each blow into a cut with greater angular momentum: in practical terms, more cutting power. In addition, the clarity of the main edge and a false edge located in the final third allow for a combination of movements: horizontal slashes, flanking blows, and, when the situation demands it, precise thrusts towards soft areas of the opponent.

Ancient literary sources and iconographic representations, such as the relief of the Warrior of Osuna or ceramics found in sites like Libisosa, show horizontal attacks and blows aimed at the abdomen, confirming the practical function of its shape. The presence of grooves on the blade, beyond aesthetic appeal, served to lighten and maintain the rigidity of the piece.

Origin and evolution: it was not an isolated invention

Although today we closely associate the falcata with the Iberian peoples, its genealogy is part of a broader Mediterranean tradition. Asymmetrical curved swords appeared on the Balkan and Adriatic coasts from a very early period (10th century BC), evolving into forms such as the machaira and the kopis. From the 7th century BC, these typologies spread to Greece and the Italian peninsula and, subsequently, reached Iberia, where local armorers adapted and transformed the design.

The Iberians shortened the original length, reinforced the tip with a double edge, and worked the blade to make it lighter and more resistant. The result was a distinctive falcata: similar in spirit to Mediterranean weapons but with purely Iberian characteristics.

Geographical distribution and chronology

Most documented falcatas come from Upper Andalusia and the southeastern peninsula; they were neither homogeneous nor exclusive to the entire peninsula. The most representative phase is located between the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, coinciding with the full formation of an Iberian warrior panoply that responded to combat tactics in formation and also to local guerrilla actions.

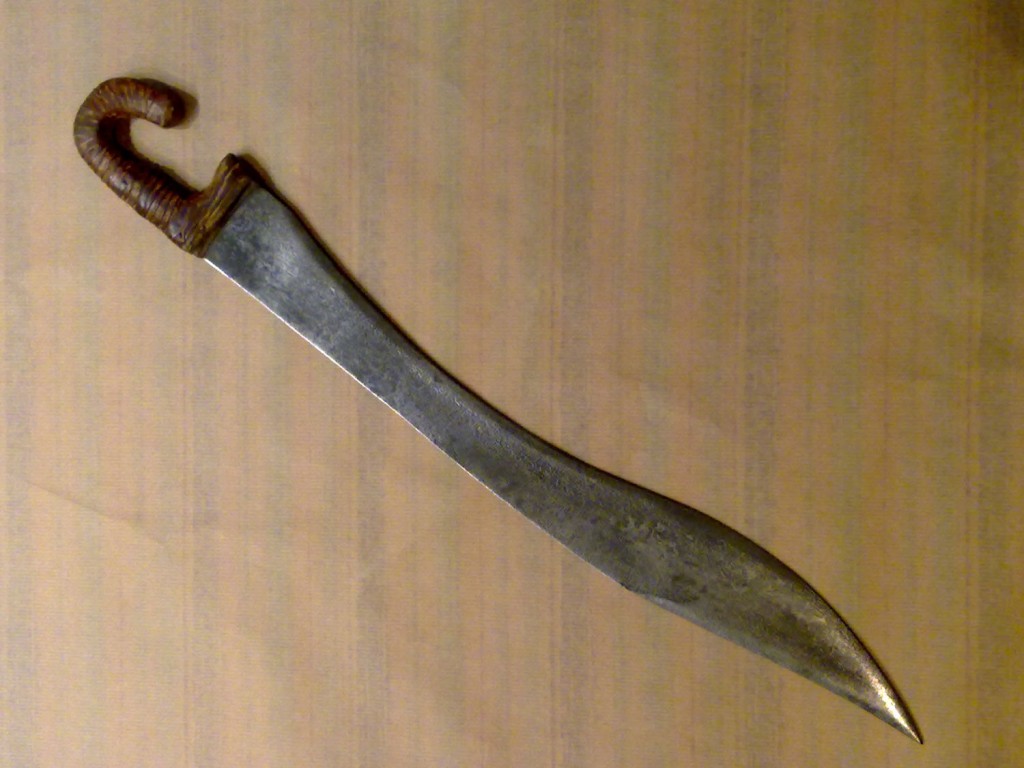

Construction and forging: three welded layers and unique hilts

The constructive technique of the falcata reveals a complex process: metallographic analyses show pieces formed by three hot-welded iron sheets (“a la calda” technique). The central, wider sheet extended to the core of the hilt and was covered with bone or wood scales, creating a solid assembly with fewer stress points at the blade-hilt joint.

This manufacturing method allowed for lightweight yet resistant blades. Although the technique, according to some studies, did not reach the metallurgical sophistication of the Romans or Greeks, the Iberian blacksmiths knew how to optimize resources and treatments to give their weapons great durability and a characteristic dark tone due to anti-corrosion treatments and the iron patina.

The hilt as a mark of identity

One of the hallmarks of the falcata is its hilt: often enveloping, designed to protect the hand, and frequently decorated with zoomorphic motifs (horse heads, birds, etc.). Some pieces feature silver wire damascening and rich ornaments that make them objects of prestige, not just war tools.

The integration of the blade with the metal core of the hilt prevented looseness and improved force transmission, something critical in a weapon designed for forceful blows. The resulting ergonomics facilitated firm grips and quick maneuvers at short distances.

Combat use: techniques, tactical advantages, and limitations

The falcata was especially effective in short-range maneuvers: lateral blows, horizontal cuts aimed at the flank of the shield or the legionary’s body, and final thrusts with the false edge. Its design allowed for impacts that could slice through mail or damage iron shields, although the idea that it easily broke helmets is part of the popular myth amplified by literary sources.

- Advantages: concentrated cutting power at the tip, versatility between cutting and thrusting, suitable for infantry in closed formation.

- Limitations: shorter reach compared to long swords or spears, dependence on proximity to maximize effectiveness.

In many combat scenes, the falcata appears as a complementary weapon within a broader equipment: shield, body protection, and, at times, spears. It was not an isolated weapon but part of an organized fighting style.

Did the Romans fear it?

It is common to read that the Romans had to reinforce their shields after contact with the falcata because this weapon cut much more easily than straight swords. This statement contains some truth regarding psychological impact, but historiographically it is excessive. The Romans already knew curved weapons and had experience with La Tène type weapons and other short swords that gave rise to the gladius hispaniensis. Changes in Roman defenses were more linked to the diversity of enemies and types of weapons than to a single typology.

Falcata and ritual: when the sword transcends the military

Beyond the battlefield, the falcata was a powerful social symbol. The presence of highly ornamented examples in funerary contexts indicates that the sword had a clear status value. In tombs, it is common to find falcatas burned, bent, or with a blunted edge after striking a rock; this forms part of a funerary ritual that required the weapon’s disappearance with its owner to prevent its reuse.

Some exquisitely decorated pieces, with damascening and zoomorphic motifs, seem destined for ritual or ceremonial acts rather than everyday combat, although this does not imply that they ceased to be operational.

Iconography and symbology

Engravings, metalwork, and the repertoire of animal motifs suggest an identity and heraldic significance. The falcata functioned as a distinctive mark of the warrior elite: carrying it meant having an elevated place in the social and military hierarchy.

Metallurgical technique: between tradition and local innovation

Although the supposed superiority of Iberian forging is often extolled, current studies show that the technique was more artisanal than technological compared to Roman-Greek metallurgical centers. Nevertheless, the skill of local blacksmiths in manipulating iron, welding sheets, and applying treatments that improved resistance and delayed corrosion was crucial for falcatas to be reliable in combat.

The result was a robust weapon, relatively light, and with a characteristic patina that made it recognizable.

Archaeological distribution and limits of the myth

Although the image of the falcata has spread as an icon of the Peninsula, the archaeological reality shows specific territorial concentrations: Upper Andalusia and the southeast are the areas with the most findings. Therefore, it was not a homogeneous or exclusive element of all Iberian peoples.

During the Late Bronze Age and until Romanization, the Iberian panoply evolved, and the falcata was a prominent piece in certain regional contexts, reflecting organized warfare practices and tactics adapted to the terrain and the enemy.

The most notable pieces and their historical significance

There are richly decorated falcatas that serve as testimony to aristocratic power and complex rituals. These pieces were not only weapons but insignia. Their study allows for a better understanding of the social hierarchy, economy, and exchange networks that connected the Iberian peoples with the rest of the ancient Mediterranean.

Examples of interest

- Falcatas with damascening and zoomorphic motifs showing Mediterranean influences and local artisans.

- Pieces found in tombs with evidence of ritual treatment (bent, burned, blunted).

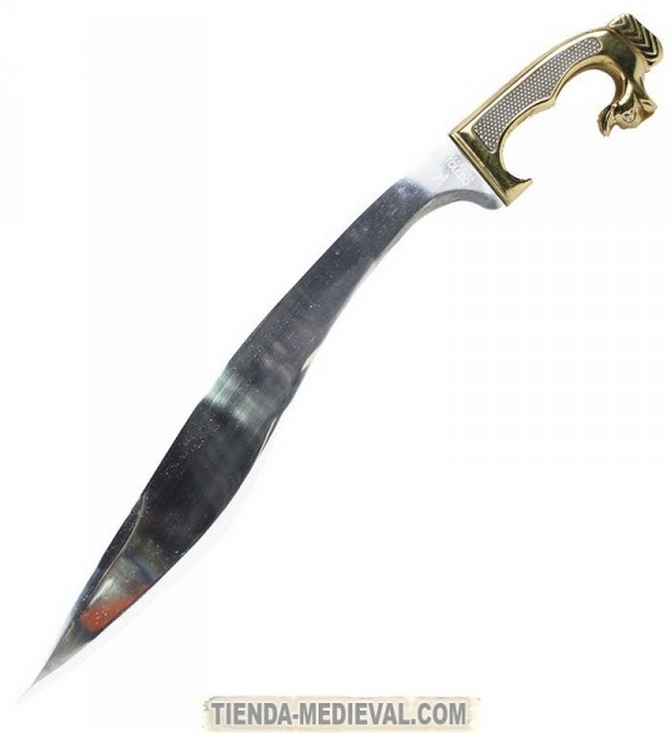

- Functional models forged in Toledo as modern replicas, available for historical reenactment and collecting.

Where to acquire replicas and functional specimens today

The market for replicas and functional pieces has grown: specialized stores manufacture falcatas based on historical models, from decorative versions to carbon steel forged replicas ready for reenactment or cutting. In our online store, we offer various models, from latex versions for LARP to high-quality replicas made in Toledo by master armorers.

When buying, consider the intended use (decorative, reenactment, training) and the quality of the steel, the type of hilt, and whether the piece includes a scabbard or not. Functional falcatas usually feature blades forged from steels such as 1065 or high-quality stainless steels in decorative versions.

For collectors, pieces with damascening or decorative details increase their value, while for reenactment and training, solidity and safety are prioritized (blunt or treated blades for training).

The cultural legacy of the falcata in museums and modern studies

Today, the falcata is the subject of exhibitions, research, and publications that attempt to separate myth from reality. Its presence in museums on the peninsula helps to reconstruct social and military aspects of the Iberians and to understand processes of cultural exchange in the ancient Mediterranean.

Furthermore, interest in the falcata has led to the contemporary manufacture of replicas, the realization of historical reenactments, and metallurgical studies that continue to yield data on techniques and uses.

Why the falcata continues to fascinate

The falcata attracts because it combines functional design and symbolic beauty: an effective weapon that also acted as an emblem of status. Its ability to tell stories—of war, craftsmanship, and ritual—makes it relevant beyond its belligerent use.

By studying the falcata, we better understand the dynamics of power, the importance of the warrior in the Iberian elites, and the connections that united Iberia with the ancient Mediterranean world.