The Roman spatha is one of the most decisive pieces for understanding the military transition between classical Rome and Late Antiquity. Why did a long sword, with Central European roots, come to replace the iconic gladius and change the way of fighting? This article offers a comprehensive overview: dimensions, origin, anatomy, typological variants, tactical use, archaeological finds, and its later influence on medieval swords.

Measurements of the Roman Spatha

The length of the Roman spatha varies according to the examples and periods; studies and archaeological findings place the blade between 70 and 100 centimeters, with 75 to 90 cm being the most common. The width usually ranges between 4 and 6 cm, and its weight is approximately 1 kg in most functional pieces, which makes it manageable both on foot and on horseback. These measurements provide it with greater reach than the gladius, and that is why it was preferred for cavalry and, over time, by Late Roman infantry.

Origin and Diffusion: from Celtic sword to Roman standard

The spatha has an origin clearly linked to the Central European swords of the Second Iron Age, adopted by Celts and Germanic peoples. Rome incorporated it from the 1st century BC, initially in the cavalry, where its greater length was advantageous. Over time, auxiliary units—many of Germanic origin—favored its spread within the army, until, from the 3rd-4th century AD, the spatha became the standard weapon in much of the Empire.

Why did Rome adopt the spatha?

- Greater reach and versatility: suitable for blows and thrusts, especially useful on horseback.

- Influence of auxiliary troops: Germanic and Celtic auxiliaries already used it and introduced it into Roman weapon factories.

- Tactical changes: combat became more mobile and less focused on the close-quarters combat of the gladius.

The spatha in heavy infantry and the replacement of the gladius

The transition from the gladius (a short weapon designed for close-range stabbing) to the spatha (a longer sword oriented towards slashing) reflects a tactical transformation. From the late 3rd and early 4th centuries, the spatha gained acceptance among legionaries and cavalrymen, becoming a common weapon in heavy infantry. The gladius moved to a secondary role or more specialized uses.

Tactical Implications

- Greater distance from the enemy: reduction of close contact and more use of slashes.

- Adaptation to less rigid formations: maneuverability in campaigns and against adversaries with light cavalry.

- Diverse military culture: the so-called “barbarization” of the Late Roman army brought styles and decorations adopted by the military elites.

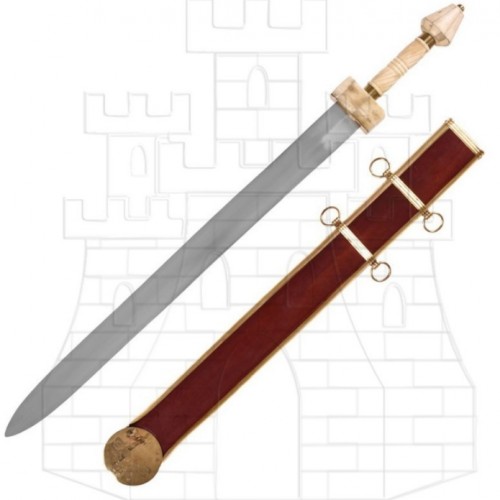

Anatomy of the spatha: blade, hilt, and scabbard

To understand the spatha, it is useful to break it down into its elements: blade, hilt (grip, pommel, and quillons), and scabbard (mouth and chape). Each part evolved according to functional needs and aesthetic fashions, and the combination of shapes allows for dating pieces and understanding their provenance.

The blade

Late Roman blades show variety: from wide models with parallel edges to narrow and elongated blades. Many examples feature a central rib that increases rigidity. The most used typologies in studies include those proposed by Biborski–Ilkjær and Miks, which describe families such as Nydam-Kragelund, Snipstad, Osterburken, or the striking Asian/Pontic type with wide quillons and cloisonné technical decoration.

The hilt

The hilt shows everything from simple solutions (wood wrapped in leather) to luxurious grips with gold plating, cloisonné, and stone pommels. Classical classifications (e.g., Behmer) describe types I to VI, with chronological and geographical variations ranging from the 3rd to the 7th century.

The scabbard

Scabbards, although mostly organic, survive through their metal plates and fittings. Types of mouths and chapes (e.g., Nydam II, Gundremmingen, or Samson) allow for the identification of production centers and periods. The suspension system was also important: from a single ring to double systems after 400 AD, reflecting changes in carrying style and aesthetics.

Classifications and types: a practical guide

| System | Type | Characteristics | Approximate Chronology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biborski–Ilkjær | Nydam-Kragelund / Snipstad | Blades with grooves and variations in width; common models in Northern Europe. | 3rd–4th C. AD |

| Miks | Lauriacum-Hromówka / Osterburken-Kemathen | From extremely wide and short blades (slashing) to long and narrow blades (thrusting). | 2nd–6th C. AD |

| Hilt Typology (Behmer) | Types I–VI | From simple wooden grips to pyramidal iron pommels and cloisonné decorations. | 3rd–7th C. AD |

Functional Comparison: Spatha vs. Gladius

| Aspect | Gladius | Spatha |

|---|---|---|

| Blade Length | 40–60 cm | 70–100 cm |

| Preferred Use | Classical infantry, thrusting | Cavalry and late infantry, cutting and thrusting |

| Advantage | Effectiveness at very short distances | Greater reach and versatility |

Archaeological Finds and Geographical Distribution

Spathae have been found in wide areas: from tombs and grave goods in the barbaricum (Germany, Scandinavia) to burials and military contexts within the Empire. Many examples come from warrior burials and elite grave goods; others are part of battlefield finds. The abundance of pieces in Germanic and British territories reflects both local production and the circulation of Roman weapons abroad.

Manufacturing and Metallurgical Techniques

Forging techniques varied according to time and place: from blades forged in a single piece to models with riveted tangs and decorative applications. Techniques such as riveting the tang to the pommel, folding the steel to improve resistance, and ornamentation in brass, bronze, or silver were applied. Roman fabricae armorum contributed to a certain homogenization of the product, although the loss of state control towards the 5th century increased variety and local production.

Decoration and Symbolism

Many late spathae feature ostentatious decoration on pommels and quillons, with enamels and cabochons. This ornamentation not only serves an aesthetic function: it acts as a sign of military prestige. The presence of richly decorated pieces in tombs (for example, the famous spatha from Childeric’s tomb) underscores the importance of the sword as a status symbol.

The Spatha in Imagination and Medieval Evolution

The linguistic and functional legacy of the spatha is clear: the word “sword” itself derives from spatha. Its long form and its function of slashing and thrusting inspired the early medieval swords that would dominate Europe during the Early Middle Ages. The robust design and ergonomics of the spatha were so successful that many technical elements were maintained for centuries.

Real Examples and Case Studies

In addition to the aforementioned typological types, there are concrete examples that help to understand regional and chronological variation. Finds in Illerup Ådal, Nydam, and various burials in Great Britain and Germany provide material for classifications and for dating transformations in the hilt and scabbard.

How to identify a spatha in a museum or collection?

- Blade length (70–100 cm) and width (4–6 cm).

- Presence of tang and rivets in the hilt.

- Scabbard characteristics: metal mouth and suspension system (single or double rings).

- Decorations on quillons and pommels indicating chronology (cloisonné, cabochons, enamels).

Recommendations for collectors and enthusiasts

If you are interested in acquiring a reproduction or a functional spatha for study or reenactment, we recommend checking quality examples in our store, where you will find models inspired by historical typologies. Take into account the authenticity of the materials and fidelity to historical dimensions if the purpose is research or reenactment.

Quick Summary Table: types, uses, and periodization

| Type/Topic | Brief Description | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Cavalry Spatha | Long blades, sometimes with a blunt tip on equestrian models. | 1st–5th C. AD |

| Infantry Spatha | Sharper tip for thrusting and combined cutting. | 3rd–6th C. AD |

| Luxury Spatha | Decorated pommels and quillons, funerary use or insignia. | 4th–5th C. AD |

Key Ideas to Remember

- The spatha is not just a weapon: it is a marker of tactical change and a key piece in the construction of Late Roman military identity.

- Its diffusion has Celtic and Germanic roots, but its standardization occurred both in Roman workshops and outside the Empire.

- The evolution of blades, hilts, and scabbards offers a very useful dating tool for archaeologists.

The Roman spatha allows us to follow the trail of cultural exchanges, tactical transformations, and the birth of new military aesthetics. If you are passionate about military history or historical reenactment, spathae offer a fascinating technical and symbolic window into Late Antiquity.

VIEW MORE ROMAN SPATHAS | VIEW ROMAN GLADIUSES | VIEW OTHER ROMAN SWORDS