What Made Each Gladiator Unique in the Roman Arena?

The roar of the crowd, the sun reflected on the steel, and the dust rising with each charge: thus began the drama in the Roman amphitheaters. Gladiators were not a homogeneous group; they were armed archetypes representing peoples, trades, and tactics. Understanding the types of Roman gladiators is to comprehend a theatrical strategy that blended spectacle, politics, and military technique.

In this article, you will learn to distinguish the most important classes by their weaponry, attire, and combat style, see how their training was organized, and discover the historical evolution that shaped these icons. You will also find comparative tables to help you quickly identify differences and several historical images and replicas naturally distributed throughout the text.

Evolution of the Munera and Roman Gladiatorial Combat

The practice of gladiator combat evolved from private funeral rituals to regulated public spectacles and political tools of the Roman State. The following table presents the main milestones in chronological order.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| Origins and Early Republic | |

| 393–290 BC | Samnite Wars: Campanians celebrate banquets with fights using captured Samnites; from this, the “Samnite” gladiator type emerges. |

| 264 BC | First known munus in Rome, celebrated after the death of Brutus Pera: gladiator combats are used as a funeral obligation. |

| Punic Wars and Expansion (3rd–2nd centuries BC) | |

| From 264 BC (Punic Wars) | First references to gladiatorial rituals during the wars against Carthage; spectacles become more frequent and consolidate as Roman entertainment. |

| 207 BC | P. Cornelius Scipio organizes a spectacle in Carthago Nova, the first reference to gladiatorial combat in Hispania. |

| 206 BC | Scipio holds games in Carthago Nova where “free and distinguished men” fought voluntarily (first mentions of auctorati). |

| 3rd–2nd centuries BC (until 2nd century BC) | The munera increase in size and complexity; they remain mostly private. In the 2nd century BC, the “Samnite” type disappears as the political relationship with Samnium changes. |

| c. 125–100 BC | First reference to a gladiator’s name in a munus, indicating greater individual importance of the combatants. |

| End of the Republic | |

| 105 BC | The State organizes official games for the first time; consuls Rutilius Rufus and Mallius Maximus offer a non-religious spectacle. Leges gladiatoriae are promulgated, and the ludus of Capua is already operating under C. Aurelius Scaurus. |

| 73 BC | The ludus of Capua, owned by Gnaeus Lentulus Batiatus, is the scene of the gladiator revolt led by Spartacus. |

| 65 BC | Laws begin to be applied that set the number of gladiators; these figures would increase under Augustus. |

| 49–46 BC | 49 BC: Julius Caesar acquires the ludus of Capua and renames it ludus Iulianus. 46 BC: Caesar orders that recruits be trained in the homes of knights and senators. |

| End of the Republic | The munus becomes a great public entertainment and political tool. Initial types based on peoples (Samnites, Gauls) serve as a basis for later categories; the gallus evolves into the murmillo after the incorporation of Gaul. |

| Beginnings of the Empire (Augustus) and 1st Century AD | |

| Beginnings of the Imperial Period (Augustus) | Augustan reform: establishes the munus legitimum, creates and eliminates types of gladiators, regulates public seating, requires closed helmets (except retiarii), suspends munera sine missione, limits days and number of gladiators, and prohibits private ludi in Rome. Retiarii emerge; secutores are developed to combat them. Provocator and cataphractus disappear. |

| 1st Century BC – 1st Century AD | The fight between auctorati becomes widespread (according to Cicero) and comes to represent more than half of the combatants; representations of female gladiators appear (relief from Halicarnassus, attributed to the 1st century BC or 2nd century AD). |

| 11 AD | A law prohibits free-born women under 20 from fighting in the arena, indicating that female participation was already frequent. |

| 21 AD | Tacitus mentions a Gallic contingent of crupellarii in the revolt of Julius Sacrovir. |

| 1st Century AD | Missio (pardon) is common: only 1 in 5 gladiators is executed. Pliny the Younger describes Greek assistant trainers and the tetradic training cycle. The first mention of gladiatrix appears in a marginal note to Juvenal. |

| Mid–late 1st century AD | Possible popularization of combats between retiarius and secutor; the retiarius solidifies as an attraction in later centuries. |

| Period of Domitian and Late 1st Century | |

| 81–96 AD (Domitian) | Domitian prohibits private ludi and creates four imperial ludi (Matutinus, Magnus, Gallicus, Dacicus) linked to the Colosseum. He offers nocturnal spectacles and combats between women; the practice of leaving missio to the victor’s decision begins, which increases deaths. Gold-decorated armor is used in parades. |

| 1st–2nd Centuries AD and Rise of the Spectacle | |

| 40–104 AD | The poet Martial writes epigrams praising gladiators like Hermes. |

| 1st–2nd Centuries AD | The probability of condemnation to death in the arena increases; by this period, half of the losers died in combat. |

| 2nd Century AD and Antonine Era | |

| 2nd Century AD | The “Antonine Plague” affects the Empire. Towards the end of the period, the dimachaerus (gladiator with two swords) develops. |

| 177 AD | Marcus Aurelius and Commodus approve the oratio de pretiis gladiatorum minvendis to lower costs and facilitate the organization of munera in the provinces. |

| 180 AD | Until this date, manumissio ex acclamatione populi (release by popular acclamation) existed; thereafter, the practice changed. |

| 182 AD | Emperor Commodus acquires the Villa dei Quintili; a mosaic found there depicts a retiarius named Montanus. |

| 3rd Century AD and Crisis of the Late Empire | |

| 200 AD | Septimius Severus prohibits women from fighting in monomachiae (definitive prohibition of singular female combat). The Zliten mosaic (c. 200) shows a retiarius surrendering with a dagger. |

| 200–300 AD | Archaeological evidence: trident wounds on a skull from Ephesus and a femur with wounds from a four-pronged weapon, indicating techniques and weapons used in the arena. |

| 218 AD | The former gladiator Macrinus becomes emperor. |

| 4th Century AD and Final Decline | |

| 315 AD | Constantine I prohibits the practice of branding gladiators. |

| c. 320 AD | A gladiator mosaic shows the Ø symbol to indicate a gladiator killed in combat, reflecting registration/graphic recording practices of results. |

| End of the Munera and Fall of the Empire | |

| 476 AD | Fall of the Western Roman Empire. According to the cited sources, this event occurs 72 years after the official prohibition of the munus and 40 years after the last munus, emphasizing the decline and the educational and social importance the games had. |

How They Were Classified: Weight, Shield, and Style

Romans appreciated contrast. To maintain excitement, opposing types were pitted against each other: a heavily armed and protected fighter against a light and mobile one. Practical classification grouped gladiators into scutarii (with a large shield) and parmularii (with a small shield), but within these labels, dozens of variants emerged, each with its own identity.

Heavy Armament Gladiators (Scutarii)

These combatants relied on protection to dominate: large shield, robust helmet, and, in many cases, a short sword for the final blow.

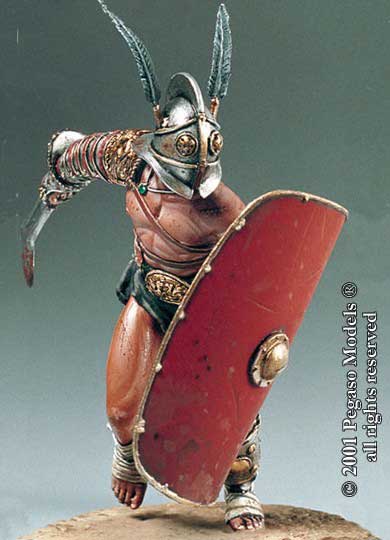

Light Armament Gladiators (Parmularii)

Agility was their argument. With small shields or none, they sought to dodge, circle, and attack openings in the opponent’s defense.

Emblematic Types: Description, Tactics, and Common Opponents

Below we present the protagonists. For easy reading, each entry shows their usual kit, tactical approach, and typical opponent.

Murmillo

Main Weapon: gladius. Defense: scutum. Identity: helmet with a high profile resembling a fish, side protection, and arm guard on the right arm. Tactics: slow approach and constant pressure, seeking close engagement where his shield dominates. Common Opponents: thraex and hoplomachus.

Thraex

Main Weapon: sica (curved sword). Defense: parmula (small shield). Identity: helmet with visor and side crest; greaves on both legs. Tactics: mobility and oblique attacks, seeking openings behind the enemy shield. Common Opponents: murmillones.

Secutor

Main Weapon: gladius. Defense: scutum. Identity: smooth helmet without ornamentation to prevent the retiarius’s rete from snagging; discreet eye holes. Tactics: harass and corner the retiarius until forcing a clash.

Retiarius

Main Weapon: trident and net. Defense: minimal; manica on the right arm and a galerus to protect the shoulder. Identity: absence of helmet and shield, style inspired by fishermen. Tactics: use of reach, nets, and feints to create stabbing opportunities. Classic Opponent: secutor.

Samnite

Main Weapon: gladius. Defense: oblong shield, helmet with visor and greave on the left leg. Identity: one of the first documented types, heavily influenced by Italic warriors. Tactics: similar to the murmillo, strong protection and thrust.

Hoplomachus

Main Weapon: spear and sword. Defense: round shield inspired by the Greek hoplon. Identity: padded leg guards, helmet with brim and plume. Tactics: use the spear to harass and then engage in hand-to-hand combat.

Provocator

Main Weapon: gladius. Defense: large shield and a protective breastplate. Identity: helmet with visor, protected by a cuirass; their role was often to open some combats. Tactics: close engagement, brute force, and resistance.

Homoplachi

Main Weapon: sword or hasta. Defense: full armor and circular shield of Greek inspiration. Identity: heavily armored, projected the aesthetic of hoplites into the spectacle.

Other Unique Types

- Crupellarii: armored to the extreme; reduced mobility.

- Scissor: with a special metal glove for cutting and trapping.

- Dimachaerus: two swords, exclusive in similar confrontations.

- Equites and Essedarii: combat from horseback or chariot.

- Cestus: boxers with reinforced gloves.

Practical Comparison: Weapons, Protection, and Style

A table helps to see the essential differences between the most representative types.

| Type | Weapons | Protection | Strategy | Typical Opponent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murmillo | Gladius | Scutum, tall helmet, manica | Pressure and closed defense | Thraex, Hoplomachus |

| Thraex | Sica (curved sword) | Parmula, greaves | Mobility and angled attacks | Murmillo |

| Retiarius | Trident and net | Manica and galerus (no helmet) | Reach, nets, and ambushes | Secutor |

| Secutor | Gladius | Smooth helmet, scutum | Harassment and encirclement | Retiarius |

| Hoplomachus | Spear and sword | Round shield, greaves | Harassing with spear and dominating at close range | Murmillo |

- Murmillo

-

- Weapon: Gladius

- Protection: Scutum, helmet

- Style: Defense and thrust

- Thraex

-

- Weapon: Sica

- Protection: Parmula

- Style: Agility and precision

Life in the Ludus: Training, Hierarchy, and Survival

The gladiator school was a microcosm where discipline and repetition forged the combatants. There, strength, technique, and strategy were worked on with mixed methods of Greek training and their own practices. Gladiators were professional athletes, and their survival depended as much on skill as on the ability to entertain.

They trained with weighted weapons, practiced in training cycles (tetrada), and followed diets rich in carbohydrates and calcium. The best could receive the rudis, the wooden sword symbolizing freedom. But the hierarchy was strict: novices, veterans, doctors, and lanistas made up a well-oiled machine.

Women in the Arena and Less Frequent Roles

Although exceptional, female gladiators existed and produced the same spectacle of courage and risk. Known as gladiatrices in modern terminology, they participated in monomachiae and, at specific times, attracted the attention of emperors and chroniclers. Over time, their presence was regulated and finally restricted.

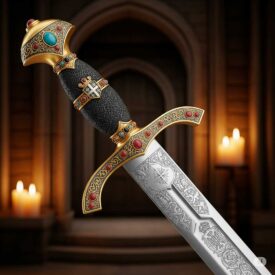

Armors, Replicas, and Collection Items

Fascination with Roman weaponry and attire has led to detailed replicas that reproduce helmets, shields, and swords. These pieces help visualize the functionality of each type and its impact on combat dynamics.

Seeing a replica of a Murmillo helmet or the design of a Thracian parmula helps understand why certain tactics were viable. Fans and reenactors value both technical accuracy and historical evocation: materials, weight, and balance are key for a faithful replica.

Myths, Spectacles, and Public Perception

The arena not only showed combat; it showed symbols. A retiarius without a helmet exchanges his face with the crowd; a secutor with a smooth helmet embodies tenacity. Planned pairings (heavy vs. light) created narratives that the public recognized and celebrated.

The most popular gladiators were celebrities with nicknames, stories, and a direct bond with the audience: their fate often depended on the people’s acclamation. That is why training included not only technique but also performance.

Injuries, Medicine, and Care

Contrary to the romantic image of immediate death, many gladiators received advanced medical attention: surgeons, bandages, and rehabilitation. The economic investment in a good fighter justified specialized healing techniques.

Legacy and How to Recognize Each Type Today

Today, mosaics, reliefs, and replicas allow for precise identification of the features that defined each gladiator. When you see a helmet with a visor and greave on the left leg, it’s easy to evoke the Samnite or the provocator; when you contemplate a net and a trident, the figure is instantly that of the retiarius.

If you are interested in reproducing a truthful arena scene, consider:

- Historical balance between weaponry and opponent.

- Details: greaves, manica, galerus, and shield type.

- Combat dynamics: heavy versus light.

Tables and Visual Resources for the Enthusiast

In addition to the comparative table, visual representations (mosaics, reliefs, and replicas) complete the learning. Interpreting them with a technical guide helps distinguish regional or chronological variants.

| Element | What it indicates | Replica Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Helmet with visor | Elevated facial protection; common in heavy types | Reproduce ventilation and eye holes for comfort |

| Large Scutum | Defensive and offensive role by thrusting | Attention to weight and curvature for realistic balance |

| Net and trident | Distance combat and movement control | Use lightweight materials for safe recreation |

A Closing that Stays with You Beyond the Arena

Roman gladiator types are more than labels; they are testimonies of how a society transformed war and representation into a ritualized spectacle. Knowing their weapons, their movements, and their history allows you to read archaeological remains with new eyes and understand why each piece — a helmet, a greave, a net — played a role in the arena’s narrative.

Every replica you examine or every mosaic you study connects you with men and women who, in their time, embodied ideals of courage, sacrifice, and entertainment. History lives on in the burnished metal and worn fabric of those times: observe, compare, and let the arena tell its own lesson.

VIEW ALL ROMAN SWORDS | ROMAN HELMETS | ROMAN SHIELDS | ROMAN STANDARDS | VIEW ROMAN THEMED STORE