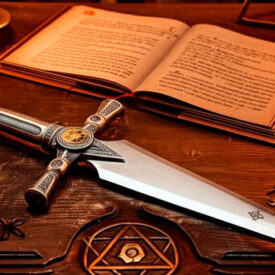

Legend has it that, in the silence after the testudo formation, the short, sharp blade of the pugio gleamed like a contained promise: a tool, a weapon, and at the same time an emblem of belonging to the legion.

A small weapon with a great history

The Roman pugio was not a sudden occurrence but the result of centuries of contacts, battles, and craftsmanship. Originating from the Iberian tradition and adapted by the Roman military machine, it became more than just a simple dagger: a daily companion of the legionary and, at times, an insignia of status within the camp.

In this article, you will explore its origin, technical evolution, use in combat, and symbolic meaning, as well as see how it was represented and transported in the Roman military. I will accompany the narration with historical visual pieces for you to discover every detail of the pugio.

The Roman pugio: chronology and evolution

The pugio went from being an Iberian dagger to a characteristic element of the Roman legionary, with both practical and symbolic functions throughout several centuries.

| Period / Date | Brief description |

|---|---|

| 2nd Century BC | Origin linked to Iberian bidiscoidal daggers; high-quality pieces and symbols of social status, as well as war trophies. |

| Late 2nd Century BC | Appear in Roman contexts as booty or through cultural exchange, although at that time they did not have great military prominence (ignored by Polybius). |

| 1st Century BC (hybridization process) | Roman armorers fuse influences from the bidiscoidal dagger and the “curved blade” dagger from the Meseta, giving way to the legionary pugio. |

| 44 BC – 42 BC | Concrete evidence of Roman use: coins linked to the assassination of Julius Caesar (44 BC) and the funerary stele of Centurion Minucius (42 BC). |

| Military reforms (late 2nd Century BC – 1st Century BC) | The professionalization of the army (Marian reforms) and the predominance of leaders like Julius Caesar favor its diffusion among the troops. |

| Augustan Era and 1st Century AD | Maximum boom: the pugio becomes widespread among legionaries and auxiliaries. Typical design: pistil-shaped blade with a rib, hilt with a tang and T-shaped grip plates, pommel with discs, metallic scabbards, and elaborate decoration. Its carrying method evolves (horizontal to vertical). |

| 1st Century BC – 2nd Century AD | Debate over its function: daily tool and secondary weapon in combat. The interpretation of military utility combined with a strong symbolic and status character predominates. |

| 2nd Century AD | A decline in its use begins due to practical and cost reasons; however, it continues to be archaeologically documented and continuous findings exist. |

| Late 2nd Century – 3rd Century AD | Rebound in findings in some contexts. 3rd-century examples maintain basic features, with possibly regional variations in size. |

| 4th Century AD | Definitive disappearance of the pugio in the Roman panoply; the arrival of new weapons (francisca, sax) and changes in foreign units explain its replacement. |

From the Celtiberian dagger to the pugio: the hybridization that changed the panoply

Roman armorers paid attention to what was useful. The bidiscoidal daggers and the curved blades from the Meseta were not just beautiful pieces: they were solutions proven in combat. The process that led to the pugio was not about copying, but about fusing.

From the Celtiberian dagger, it inherited the anatomical grip and the philosophy of the bidiscoidal handle; from the Meseta daggers, it took the robustness and the possibility of narrower blades with a central rib. The result: a short, balanced dagger capable of penetrating light armor.

Design: what a pugio was like

To talk about the design of the pugio is to talk about intention: a blade that seeks to penetrate, a hilt that secures, and a scabbard that displays. It is no coincidence that its pistil-shaped form was ideal for concentrating the blow on the tip.

The blade

Typically, it was a blade between 18 and 28 cm long, wide at the base and with one or more central ribs that served as a spine. This configuration gave it sufficient rigidity to stab effectively and resistance so as not to bend on impact.

The hilt

The hilt was assembled on a tang; two grip plates fixed by rivets formed a functional handle. A recurring element was the pommel with a disc or globule, designed to seat the wearer’s hand and prevent slippage.

The scabbard and suspension

Scabbards were a field of expression. From simple leather designs to metal covers with damascening, the pugio’s sheath could boast decoration. Suspension by lateral rings allowed it to be hung from the cingulum in a vertical position or, in earlier stages, horizontally.

How the legionary carried it

The way the pugio was carried was practical and ritualized: the almost universal custom of distributing equipment on both sides of the hip to balance weights was observed. Thus, the gladius on one side and the pugio on the other formed a visual and functional balance.

In many iconographic testimonies, it appears hanging from the cingulum, sometimes with a second belt specific to the dagger; other times, both weapons shared a single belt with various attachments.

Functions on and off the field

Although it has often been said that the pugio was a weapon of last resort, evidence suggests a multifunctional use: from everyday cutting tasks to close-combat interventions or ambushes where a short dagger proves lethal.

Its ability to pierce, thanks to the central rib, allowed it to be effective against chainmail and reinforced clothing. However, its size and design made it ideal for fighting in confined spaces and for surprise actions.

Practical use and symbol

In addition to its function as a tool, the pugio had a strong symbolic component. Decorated scabbards and metal details could indicate rank or belonging to a specific unit. It was a personal object with a marked identity value.

Variants and typologies

Over time, different types of pugio can be appreciated: from short and blunt examples to others longer and more stylized. Some variations obey technical changes, others local fashions or the specific function they had to fulfill.

- Hispano-Roman Pugio: evident Iberian influence in handle and decoration.

- Imperial Pugio: with elaborate scabbards and presence in contexts of greater prestige.

- Utilitarian Pugio: simpler pieces, frequent among auxiliary troops or in non-prestigious contexts.

Manufacture and materials

The blade was forged from iron or steel according to the available technique; the central rib could be achieved by rolling or forging. The hilt scales were made of wood, bone, or metals, and the scabbards combined leather, wood, and metal coverings with ornamentation.

The artisans who produced pugios had to balance cost, resistance, and aesthetics: a scabbard rich in silver or with damascening implied greater social scrutiny and resources from the owner.

Iconography and representation

On stelae, reliefs and coins, the pugio appears with some regularity in the late Republican period and in the initial centuries of the Empire. Its appearance on a funerary stele bore witness to the central role of the pugio in military identity.

The representation of the pugio also allows us to understand the evolution of its suspension: sometimes we see it horizontally, other times vertically, on the opposite side to the gladius, which reflects practical changes in its carrying.

The pugio in the hands of historical figures

Iconographic sources and some material testimonies place the pugio in symbolic scenes: from official inscriptions to coins that incorporate it as a symbol at key moments, such as the assassination of Julius Caesar.

Although it is always impossible to attribute specific acts, the presence of the pugio in coins or steles reinforces the idea of its value beyond simple practical use.

Maintenance and care (ancient practices)

Legionaries knew the importance of maintenance: filing the blade, oiling the scabbard, and repairing the leather were common tasks. A well-maintained dagger was not only more reliable, but also conveyed an image of discipline.

In long campaigns, the strength of the rib and the integrity of the tang were crucial; for this reason, designs that allowed for quick repairs in the camp were preferred.

The legacy of the pugio and its disappearance

After its heyday in the 1st centuries BC and AD, the pugio began to lose its presence in the Roman panoply as new tactics and weapons were introduced. The 2nd century AD marked a gradual decline, and by the 4th century AD, the dagger had disappeared as a standard military element.

However, its imprint endures: archaeological pieces and modern replicas remind us that the pugio was more than just iron and leather; it was a component of identity, practice, and military aesthetics.

Studying the pugio reveals how Rome assimilated foreign techniques and objects, transforming them into tools adapted to its professional army. It is a lesson in technological and cultural hybridization: what arrived at the camp was not adopted as is, it was adapted, improved, and integrated.

Furthermore, understanding its design and function helps reenactors, artisans, and history enthusiasts to interpret the material life of the legionary with greater fidelity.

Practical reading for the enthusiast

- Observe the hilt: the central knot and the pommel reveal ergonomic intent.

- Look at the rib: more than one indicates a search for rigidity for piercing.

- Look at the scabbard: the decoration can suggest rank or origin.

These simple observations will help you differentiate original specimens, faithful replicas, and stylistic variations.

Today as yesterday, the pugio continues to fascinate. It is not just a dagger: it is a tangible fragment of how the Romans thought about war, status, and appearance. Its silhouette, small but full of meaning, invites us to look beyond the steel and understand the lives of those who carried it.