What makes a small dagger deadly? Imagine the silence after the clash of swords, the metallic rustle of chainmail, and the bated breath of two combatants. In that instant, a short, rigid blade can decide fate: that is the essence of the rondel dagger, a weapon designed to penetrate an opponent’s protection with precise and merciless thrusts.

In this article, you will learn why the rondel became an essential tool during the Late Middle Ages, how its form evolved to accommodate armored combat, what historical techniques explain its effectiveness, and how it differs from contemporary weapons like the stiletto. You will also see how modern replicas reinterpret this design for historical reenactment and practice.

The Rondel Dagger: Evolution and Historical Milestones

Before delving into techniques and construction, it’s important to place the rondel in time. Its history is not one of a passing fashion, but rather an effective response to the emergence of increasingly protective armor.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| Late 12th Century — Early 13th Century | |

| Origin | Rondel daggers appear in Europe, derived from dagger types used during the 12th and 13th centuries. |

| Until 1400 | |

| Before 1400 | The rondel dagger was commonly used among the peasant class, serving as both a tool and an everyday weapon. |

| 14th Century | |

| Early 14th Century | Period of increasing popularity of the rondel dagger in Europe, especially from the beginning of the century. |

| Around 1350 | The rondel dagger adopts its distinctive shape in regions like France, England, and the Low Countries. |

| 1358 | Mentioned in the context of the Jacquerie peasant revolt; some manuscript depictions may be later. |

| 1380–1400 | Manuscripts from this period depict conflicts with armor and contemporary weapons, showing rondel daggers in battle scenes. |

| 15th Century | |

| General Use | It becomes a standard weapon for knights and gains popularity among the emerging middle class (merchants and artisans); this century is considered a peak in its use. |

| 1415 | Used in the Battle of Agincourt. |

| 1440–1460 | Hans Talhoffer’s combat manuals detail multiple fighting techniques with rondel daggers. |

| Around 1448 | Miniatures, such as that of Girado de Rosselló, show merchants and artisans wearing rondel daggers on their belts. |

| 1467 | The Thalhoffers-Fechtbuch includes techniques for using daggers in close combat. |

| Late 15th Century (around 1500) | Examples dated to this period appear in contemporary representations and documents. |

| 16th Century | |

| Continuity | The rondel dagger continues in use during the 16th century, albeit in a military and civil context different from the early medieval period. |

| Present Day | |

| Reproductions and Study | Modern replicas, used in historical reenactment and Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA), are usually manufactured with rounded tips and unsharpened blades for safety. The design and functionality of the rondel dagger continue to be subjects of research and appear in popular culture. |

- Chronology: Key points to remember

-

- Origin: Late 12th and early 13th centuries.

- Expansion: 14th-15th centuries, adopted by various social strata.

- Manuals: Techniques documented in 15th-century treatises.

- Legacy: Current replicas for reenactment and study.

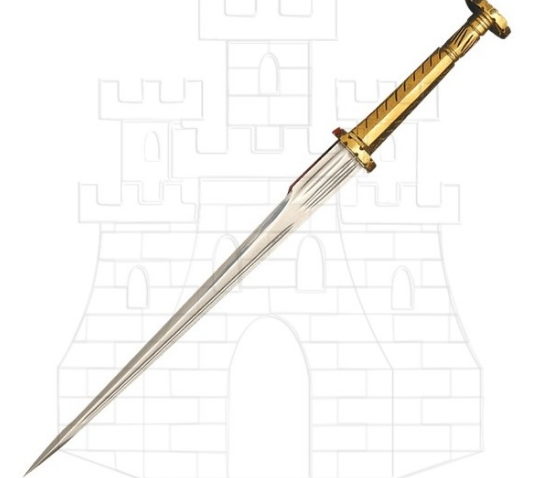

How a Rondel is Made: Elements and Materials

The design of the rondel is conceived with a very specific purpose: to concentrate the energy of the thrust into an extremely rigid point. Each component exists to ensure that point reaches where it should.

Blade and Cross-Section

The blade is short compared to a sword, but remarkably rigid. It often has a triangular or lenticular cross-section, heavily reinforced towards the tip. This geometry prevents bending when impacting hard surfaces like armor steel.

Guard and Pommel (the ‘rondels’)

The round disks or rondels on the guard and pommel serve two practical purposes: to protect the wielder’s hand and to allow a stable grip when applying thrust and torsion. They can also act as a stop to block short weapons during grappling.

Handle and Scabbard

Handles were made of wood covered with leather, and sometimes with inlays or decorative threads. The scabbard, normally made of leather with metal reinforcements, had to allow quick access in close combat.

Tactics and Technique: Why it Worked in Armored Combat

In hand-to-hand combat with full armor, the fight was not elegant: it was shoves, levers, and thrusts into specific gaps. The rondel excelled in this fight because it was designed for localized thrusts.

- Objective: strike seams, armpits, groin, and joints between plates.

- Maneuver: force an opening with the dagger using leverage or taking advantage of the opponent being off balance.

- Concentrated Force: the rigid cross-section of the blade transmits force to the tip, allowing it to pierce materials that a wide sword could not.

Techniques described in treatises

15th-century manualists explain various dagger techniques: inverse grips, use in combination with the free hand to create openings, and how to convert a thrust into enemy body control. The rondel, due to its design, favors short wrist movements and pushes, not long sweeps.

Comparison: Rondel Dagger vs. Stiletto

At first glance, both seem designed for piercing, but their history and anatomy differ. The following table synthesizes these differences to understand why they coexisted and for what purpose each was preferred.

| Characteristic | Rondel Dagger | Stiletto |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Origin | From late 12th century, widespread in 14th–15th centuries | Defined in mid-15th century, popular in 16th century |

| Blade Design | Rigid blade, triangular or lenticular cross-section, robust tip | Very thin and elongated blade, sharp and often more flexible tip |

| Main Function | Pierce joints and weak points of armor in close combat | Precise piercing, also for concealment and rapid use |

| Typical Users | Knights, soldiers, and emerging middle class | Guards, officers, people who needed a hidden or light weapon |

| Combat Context | Hand-to-hand combat with armor | Both contexts: urban, military, and self-defense |

Materials, Forging, and Conservation

The original rondel was the result of blacksmiths seeking a balance between hardness and toughness. A tip that was too brittle would break; a blade that was too soft would bend when trying to pierce reinforced leather or armor.

- Carbon steel: common in historical blades due to its temper and maintenance.

- Treatments: local tempering at the tip to increase penetration.

- Finishes: wooden handles, leather, and metal adornments to refine grip and aesthetics.

Civilian and Symbolic Uses

Far from being exclusive to battlefields, the rondel appeared at the waists of merchants, artisans, and travelers. In urban contexts, it served both as a personal defense tool and a symbol of status in certain latitudes and historical moments.

The Rondel in the Hands of the Populace

For many people, the rondel was an everyday item: small, accessible, and effective. Its presence denotes that medieval material culture anticipated the need for personal defense in both rural and urban environments.

Replicas, Historical Reenactment, and Related Products

Contemporary interest in living history and Historical European Martial Arts has driven the manufacture of replicas. These retain the original aesthetic but adapt safety for use in reenactment.

When evaluating replicas, you should pay attention to: tang construction, blade rigidity, steel type, and scabbard quality. Versions for HEMA or events use rounded tips and unsharpened blades, while display replicas may have more refined finishes and sharpened tips oriented towards collecting or decoration.

Basic Maintenance

Cleaning the blade with oil, checking the integrity of the tang, and keeping the scabbard away from moisture are basic care steps. For replicas with adornments, clean with appropriate products according to the material to preserve the appearance without damaging the metal or coatings.

Practical Cases and Historical Examples

The rondel appears in sources describing fights in enclosed spaces or at the end of pitched battles when the distance between opponents is reduced. Illustrations of battles and 15th-century fencing treatises offer examples of how thrusting, leverage, and control techniques were applied alongside the dagger.

What the Manuals Say

Treatises of the era describe alternative grips, wrist strikes, and techniques to leverage greater body weight than the adversary. The goal was not to wound with cuts, but to incapacitate or inflict injuries that would compel a request for ransom or surrender on the battlefield.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Was the rondel deadly? Yes. Its ability to pierce joints and deep tissues made it a very dangerous weapon in expert hands.

- Was its use taught? Yes, manuals and weapons masters detailed specific techniques, especially in the 15th century.

- Why wasn’t the blade sharpened? The way it was used prioritized rigidity and penetration; excessive sharpness did not improve its thrusting function against armor.

Through these answers, the logic guiding its manufacture and use becomes clear: the rondel was a precise solution to a specific problem.

Your Perspective After Reading

The rondel dagger is not just an object; it is evidence of how weapon engineering adapts to the protection it encounters. From the rigid blade to the rondels on the guard and pommel, every feature responds to the same directive: concentrate energy, control the enemy’s body, and win the combat in the most intimate space.

If you are interested in military history, the conversion of historical pieces into replicas, or historical fighting techniques, the rondel offers a fascinating field of study: practical, technical, and deeply human, because ultimately it speaks of survival and skill in extreme situations.