In the heat of the Battle of Roncesvalles, while the echo of the olifant resonated among the Pyrenean mountains, a Christian paladin wielded a sword that guarded in its pommel the most sacred relics of Christianity. That weapon, indestructible and divine, was Durandal, Roland’s legendary sword that defied the rock itself and whose final destiny remains shrouded in mystery and medieval tradition.

Durandal, also known as Durandarte or Durindana, is more than a simple medieval sword: it is a symbol of faith, loyalty, and bravery that has transcended centuries to become one of the most celebrated weapons in European epic literature.

Durandal and Roland: milestones and appearances of the legend throughout time

The legend of Roland and his sword Durandal has roots in the 8th century but consolidates and transforms through medieval texts, pilgrim traditions, and cultural manifestations up to the present day. Below is an ordered chronology of the most relevant milestones:

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| 8th Century: historical context and death of the hero | |

| 8th Century | Reign of Charlemagne. |

| 8th Century | Life of Roland. Roland is a legendary hero situated in the 8th century. |

| Before his death (8th Century) | Appointment and delivery of Durandal. Roland received the sword from Charlemagne when he was knighted at 17 years old. |

| August 778 | Battle of Roncesvalles. Charlemagne was returning from the siege of Zaragoza; in this campaign, the combat in which Roland would be defeated took place. |

| August 15, 778 | Death of Roland (historical/legendary version). Date traditionally marked as the death of Roland in Roncesvalles. |

| Middle Ages: composition and diffusion of the legend | |

| 11th Century | Composition of the known version. Roland’s figure is shaped in the context of the Reconquista. |

| 12th Century | Diffusion with the «Chanson de Roland» (Song of Roland). The epic poem widely popularized the figure of Roland in medieval Europe. |

| 13th Century | Rocamadour as a pilgrimage center. Rocamadour appears as a place of worship and is associated with the place where Durandal fell or was stuck. |

| 14th Century | Galician translation of Pseudo-Turpin. The book «La Conquista de Hespaña por Calomagno» was translated into Galician, contributing to the peninsular diffusion of the legend. |

| Modern and Contemporary Eras | |

| 2011 | Exhibition of the Rocamadour sword. The sword associated with Durandal was extracted and lent to the Cluny Museum in Paris. |

| June 21-22, 2024 | Theft of the Durandal replica. The theft of Durandal from the Rocamadour sanctuary occurred. |

- 8th Century: historical context and death of the hero

-

- Reign of Charlemagne and life of Roland

- Appointment: Roland received the sword from Charlemagne when he was knighted at 17 years old

- August 778: Battle of Roncesvalles

- August 15, 778: Death of Roland in Roncesvalles

- Middle Ages: composition and diffusion

-

- 11th Century: Composition of the known version

- 12th Century: Diffusion with the «Chanson de Roland»

- 13th Century: Rocamadour as a pilgrimage center

- 14th Century: Galician translation of Pseudo-Turpin

- Contemporary Era

-

- 2011: Exhibition of the Rocamadour sword at the Cluny Museum

- June 2024: Theft of the Durandal replica from the Rocamadour sanctuary

The origin of Durandal: a divine gift forged in mystery

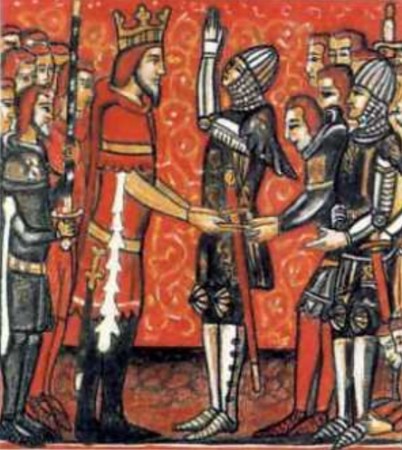

Roland, paladin of Charlemagne and central figure of the Matter of France, received the sword Durandal when he was knighted at 17 years old. According to literary tradition, it was Emperor Charlemagne himself who presented this legendary weapon to his nephew (a purely literary kinship, as Roland was considered the son of Gisela of France, Charlemagne’s sister).

However, other versions of the legend claim that Durandal was given to Roland by an angel, or that it was forged by the mythical Welsh smith who also created Charlemagne’s sword Joyeuse, thus adding a supernatural and divine nuance to its origin.

What all versions agree on is the extraordinary character of this weapon, endowed with qualities that transcended the merely physical.

Durandarte: the meaning of “the lasting one”

In Spain, Roland’s sword is known as Durandarte, a name that means “the lasting one” or “indestructible.” This name is no coincidence: it directly refers to the sword’s most outstanding quality, its inability to be broken or damaged.

This characteristic would be dramatically demonstrated at the most crucial moment of Roland’s life, when he tried to destroy it to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. Durandal’s legendary resistance became etched in the European collective memory as a symbol of the unwavering strength of the Christian faith.

The sacred relics: Durandal’s divine power

What truly distinguishes Durandal from other legendary swords is its condition as a sacred reliquary. In the golden pommel of the sword, Christian relics of incalculable spiritual value were kept:

- A tooth of Saint Peter, the founding apostle of the Church

- Blood of Saint Basil, one of the great fathers of the Eastern Church

- Hairs of Saint Denis (some versions mention Saint Basil), martyr and patron saint of France

- A fragment of the mantle of the Virgin Mary, the mother of Christ

These relics transformed Durandal into more than a weapon of war: it was an object of devotion, a tangible symbol of the Christian faith and the struggle against the “infidels” in medieval Europe. The presence of these sacred objects endowed the sword with almost magical power and conferred divine protection upon its wielder.

The glittering golden pommel was not just a decorative element, but the receptacle for these influential relics that turned every blow of Durandal into an act of faith.

Roland: Charlemagne’s paladin

Roland, also known as Rolando in Italian and Orlando in Southern European traditions, was a historical commander of the Franks serving Charlemagne. He held the title of Count of the March of Brittany, a position of great military relevance in the Carolingian administrative structure.

However, history has embroidered his figure into the epic tale of the Christian noble killed by Saracen forces, which forms a central part of the Matter of France, one of the three great epic cycles of European medieval literature along with the Matter of Britain (Arthurian cycle) and the Matter of Rome.

This character has been surrounded for centuries by a mythological aura that has left its mark throughout the Pyrenean geography and northern Spain.

The Battle of Roncesvalles: a hero’s last day

On August 15, 778 (some sources mention 788), in the Roncesvalles pass, in the Navarrese Pyrenees, the battle that would seal Roland’s destiny and turn Durandal into an eternal legend took place.

Charlemagne was returning from the siege of Zaragoza when the rearguard of his army, commanded by Roland and the Twelve Peers of France, was ambushed by Basque forces. In this epic battle, Roland demonstrated his valor until his last breath.

The sound of the olifant

According to La Chanson de Roland (The Song of Roland), the 11th-century epic poem that immortalized these events, Roland blew his war horn, the olifant, to call for help when the situation became desperate. The sound was so powerful that it was heard miles away, but it was too late.

Charlemagne, upon finally reaching Roncesvalles, found the corpse of his nephew with the sword Durandal by his side, a silent testimony to the paladin’s last stand.

The attempt of destruction: when the rock broke

One of the most dramatic moments in the legend of Durandal occurs in the last moments of Roland’s life. Aware of his imminent end and fearing that his precious sword would fall into the hands of the Basque enemies (whom Christian chronicles called “infidels”), Roland attempted to break Durandal by striking it against a rock in the Pyrenees.

The result was astonishing: the sword proved its indestructible nature. Not only did it not break, but it was the rock itself that split upon impact. This proof of the weapon’s legendary quality was recorded in the Song of Roland and in The Song of Roncesvalles.

At this critical moment, Roland mentions the sacred relics that the sword guarded, acknowledging that Durandal was too valuable—both materially and spiritually—to allow it to be defiled.

Roland’s Breach: the stony miracle of the Pyrenees

In the Ordesa and Monte Perdido National Park, at an altitude of 2,804 meters, there is a natural opening in the mountain that measures over 60 meters high and 25 meters thick. This geological formation connects the French Gavarnie Park with the Spanish Ordesa Park, and is known as Roland’s Breach (Bréche de Roland).

The legendary versions of the Breach

There are several versions of how this spectacular opening was formed:

Version of the desperate blow: Roland, desperate to prevent Durandal from falling into other hands, swung the sword with such fury that the steel opened a breach in the natural mountain wall. Through this opening, Roland was able to gaze at the sky one last time. However, the superhuman effort caused the veins in his neck to burst, ending the hero’s life.

Version of the divine lightning: Another tradition asserts that when he brandished the sword vertically, it attracted an electric spark from the sky that carbonized the character while the enormous slash broke the stony wall, but without time for Roland to pass through it.

Version of the military pass: According to some legends, Roland opened the Breach with a blow from Durandal to allow his army to pass into Gaulish territory on their return to France.

Roland’s footprints in Spanish geography

The character of Roland has left his legendary mark in multiple places on the Iberian Peninsula and southern France, a testament to the cultural impact of his legend:

- Roland’s Steps: Between Roncesvalles and Mezkiritz (Navarra)

- Roland’s Rocks: On the coast in front of Hendaye, supposedly thrown by him from the Peñas de Aya

- Roland’s Breach: In the Ordesa and Monte Perdido National Park

- El Pierrondán: Supposed footprint of Roland’s foot in Fuencalderas (Cinco Villas region, Aragón)

- Roland’s Jump: In the Sierra y Cañones de Guara Natural Park (Huesca), two peaks that, according to legend, Roland had to jump to escape his pursuers. His horse died from the effort and Roland had to continue on foot until he reached Ordesa

- Roland’s Crag: In Reboira (Vilares, Guitiriz), where tradition says that Roland left three longitudinal and parallel cuts with his sword

These places form a mythical geography that perpetuates the memory of the paladin and his sword throughout the centuries.

The mysterious final destiny of Durandal

After Roland’s death in Roncesvalles, the fate of the sword Durandal branches into several legendary traditions, each with its own narrative logic and symbolic meaning.

| Tradition | Location | Description of destiny |

|---|---|---|

| Rocamadour (France) | Sanctuary of Our Lady of Rocamadour | Roland threw the sword before dying, and it miraculously flew hundreds of kilometers to embed itself in the rock of the sanctuary, guided by divine intervention. |

| Lake of Carucedo (Spain) | El Bierzo, León | Roland threw Durandal into the lake to prevent it from falling into enemy hands, where it remains hidden. |

| Bernardo del Carpio | Peña Longa | The Leonese knight Bernardo del Carpio defeated Roland, kept Durandal, and was buried with it. Subsequently, Charlemagne recovered the sword from the tomb. |

- Rocamadour (France)

-

- Location: Sanctuary of Our Lady of Rocamadour

- Legend: Roland threw the sword before dying, and it miraculously flew hundreds of kilometers to embed itself in the rock of the sanctuary, guided by divine intervention

- Lake of Carucedo (Spain)

-

- Location: El Bierzo, León

- Legend: Roland threw Durandal into the lake to prevent it from falling into enemy hands, where it remains hidden

- Bernardo del Carpio

-

- Location: Peña Longa

- Legend: The Leonese knight Bernardo del Carpio defeated Roland, kept Durandal, and was buried with it. Subsequently, Charlemagne recovered the sword from the tomb

Rocamadour: the sanctuary of the embedded sword

The best-known tradition places Durandal in the monastery of Our Lady of Rocamadour, in southwestern France. According to the monks of the sanctuary, the sword embedded in the rock wall next to the church of Saint Michael is the authentic Durandal.

Legend has it that Roland, feeling death approach in Roncesvalles, cast his sword with his last strength. Miraculously, Durandal flew hundreds of kilometers guided by divine intervention to embed itself in the sanctuary’s rock, almost ten meters high, where it would remain safe from the enemies of faith.

The sword was chained to the cliff, near the Notre-Dame chapel. Since the 13th century, Rocamadour became an important pilgrimage center, and the sword was one of its main attractions.

The theft of Durandal in 2024

In 2011, the Rocamadour sword was extracted from the rock to be loaned to the Cluny Museum in Paris, as part of a temporary exhibition.

However, on the night of June 21-22, 2024, Durandal was stolen from the Rocamadour sanctuary. According to the sanctuary’s director, the stolen object was actually a replica described as “just a sheet metal piece” with no substantial monetary value, although of immense symbolic and cultural value to the local community and pilgrims.

This theft was not the first: the sword had been stolen and relocated multiple times throughout its history due to its fame, which eventually led to installing a copy instead of the presumed original.

Durandal in literature and popular culture

Roland’s sword has transcended its medieval origin to become a cultural icon of the first order.

The Chanson de Roland and the Matter of France

The Song of Roland (La Chanson de Roland), probably composed in the 11th century, is the most important literary source of the legend. This epic poem widely popularized the figure of Roland throughout medieval Europe and established the central elements of his story.

Other important texts include:

- El Cantar de Roncesvalles, a Spanish version of the tale

- The History of Charlemagne and Roland by Pseudo-Turpin (12th century)

- The Conquest of Hespaña by Calomagno, a 14th-century Galician translation of Pseudo-Turpin

Durandarte in the Romancero Viejo

In a Castilian version of the Romancero Viejo, “Durandarte” refers to a character who personifies Roland’s sword itself. This literary interpretation turns the weapon into a heroic figure in its own right, a unique case in medieval epic.

Festive and cultural traditions

The figure of Roland has inspired multiple cultural manifestations:

- In the mid-last century, during carnival in Nerga (Morrazo Peninsula, Pontevedra), some villagers dressed as Roland, brandishing a wooden sword in emulation of the legendary character

- The Chapter of Santiago de Compostela Cathedral celebrated masses for Charlemagne and hung the famous “horn or olifant of Roland” before the high altar in the 16th century

- In Betanzos, the palace of Don Manuel Roldán preserves the olifant on its heraldic shield

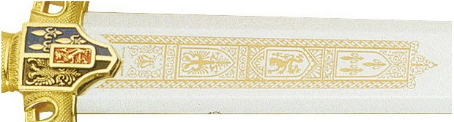

Modern replicas of the Durandal sword

Roland’s sword is part of the exclusive “Historical, Fantasy, and Legendary Swords” Collection manufactured by renowned master armorers. These replicas seek to capture the essence of the legendary Durandal with precise specifications:

- Total length: 117 cm

- Blade length: 94 cm

- Width: 21 cm

- Weight: 2.4 kg

These reproductions allow enthusiasts of medieval history and historical reenactment to connect with the legend of one of Christianity’s most celebrated paladins.

Clearing doubts about Durandal and legendary swords

What is the story behind the relics of the Durandal sword?

The Durandal sword, legendary weapon of the paladin Roland, is enveloped in a story both epic and religious. According to literary and legendary tradition, Durandal was given to Roland by Emperor Charlemagne as a symbol of his knighthood. What makes it especially unique is that it was said to house several sacred Christian relics in its hilt or structure: a tooth of Saint Peter, blood and hairs of Saint Basil (other versions mention hairs of Saint Denis), and a fragment of the mantle of the Virgin Mary.

The Durandal sword, legendary weapon of the paladin Roland, is enveloped in a story both epic and religious. According to literary and legendary tradition, Durandal was given to Roland by Emperor Charlemagne as a symbol of his knighthood. What makes it especially unique is that it was said to house several sacred Christian relics in its hilt or structure: a tooth of Saint Peter, blood and hairs of Saint Basil (other versions mention hairs of Saint Denis), and a fragment of the mantle of the Virgin Mary.

These relics endowed the sword with an almost divine character and made it practically indestructible, according to legends. It is said that faced with the possibility of falling into enemy hands, Roland tried to break the sword against a rock, but Durandal proved more resistant than the stone itself, thus highlighting its miraculous nature.

The presence of relics in the sword was not just a symbolic detail, but transformed Durandal into an object of devotion, a symbol of Christian faith and the struggle against “infidels” in medieval Europe. Thus, the story of Durandal is both that of a magical weapon and that of a religious relic, merging chivalric epic with the Christian fervor of the era.

What other legendary characters carried swords with proper names?

Legendary characters who carried swords with proper names include:

- King Arthur, with the legendary sword Excalibur or Caliburn.

- Charlemagne, who had the sword Joyeuse and another called Flambergé.

- El Cid Campeador, carried the swords Tizona and Colada.

- Roland, Charlemagne’s nephew, with the sword Durandal (or Durindana).

- Lancelot du Lac, from the Arthurian cycle, associated with a sword called Aeron-diht.

- Julius Caesar, to whom the sword Crocea Mors is attributed.

- Mark Antony, with a sword known as Phillipa (according to Shakespeare’s work).

- Siegfried (from Norse mythology), bearer of the sword Gram or Balmung.

- Characters from various cultures and legends with swords named such as Zulfiqar (sword of Prophet Muhammad according to Islamic tradition) and others mentioned in diverse mythologies.

These swords were not just weapons, but symbols of power, authority, and mythical characteristics attributed to their bearers.

How does the Durandal sword relate to other famous swords like Excalibur?

The Durandal sword, protagonist of the French legend of Roland, relates to other famous swords like Excalibur, from the Arthurian legend, in several aspects, especially in its symbolic character and its function within the European epic tradition:

- Symbol of the hero and the nation: Both Durandal and Excalibur embody the power and legitimacy of their respective heroes—Roland, Charlemagne’s paladin, and King Arthur, leader of the Knights of the Round Table. Both swords represent the connection between earthly power and the divine.

- Supernatural powers: Durandal is described as indestructible and bearing sacred Christian relics, endowing its bearer with an almost magical quality and divine protection. Excalibur, for its part, is a magical sword that shines like the sun, cuts through any material, and whose scabbard protects Arthur from being wounded.

- Connection with the stone: While Excalibur is famous for being drawn from a stone (at least in one of its versions), Durandal is also linked to a rock, as according to legend, after Roland’s death the sword was thrown and became embedded in the rock of Rocamadour, where it remained for centuries until its recent disappearance.

- Cultural legacy: Both swords transcend their martial function to become cultural and national symbols, inspiring literature, art, and collective legacy; Excalibur as the archetype of legitimate government and Durandal as an emblem of heroic resistance and Christian faith in the face of adversity.

In summary, the relationship between Durandal and Excalibur is one of legendary parallelism: both are emblematic swords, endowed with supernatural qualities and deeply rooted in the cultural identity and heroic mythology of their respective countries. While Excalibur symbolizes royal destiny and the unity of a kingdom, Durandal represents the bravery, loyalty, and unwavering faith of a Christian knight.

What is the importance of the Battle of Roncesvalles in the legend of Durandal?

The Battle of Roncesvalles is fundamental to the legend of Durandal because it is the setting where Roland, the knight who carries it, dies after being ambushed along with the Twelve Peers of France. According to tradition, during this battle, Roland blows his olifant to call for help and, facing his death, throws the sword Durandal into the water to prevent it from falling into enemy hands, symbolizing his valor and the sacred and indestructible nature of the weapon.

This battle not only marks Roland’s heroism and tragedy but also gives rise to multiple epic tales (such as the Song of Roland), which glorify both his figure and the legend of the Durandal sword, considered a divine treasure imbued with sacred relics and a key symbol of Carolingian Christian power.

Are there other versions or variants of the Durandal story in different cultures?

There is some variation in the story of Durandal across different cultures or literatures, although there are no dramatically different versions in other cultures distinct from the European one. However, there are some variants in how the story is told and its symbolism interpreted:

- The Song of Roland: This 11th-century French epic is the main source of the Durandal story. In it, Roland tries to destroy the sword to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

- Varied Legends: In some legends, after trying to break it, Roland throws it into the air, and it embeds itself in a rock in Rocamadour, France. Another variant tells that he threw it into Lake Carucedo, where it remains hidden.

- Romancero Viejo: In a Castilian version, “Durandarte” refers to a character who personifies Roland’s sword, although this interpretation is more literary than historical.

In summary, the variations mostly stem from differences in the narration of the legend within European culture itself, rather than from distinct versions in other cultures.

The eternal legacy of the indestructible sword

Durandal represents much more than a medieval weapon: it is a symbol of unwavering faith, loyalty until death, and divine power manifested in the earthly world. From the heights of Roland’s Breach to the waters of Lake Carucedo, passing through the cliffs of Rocamadour, Roland’s sword has left its indelible mark on European geography, literature, and collective imagination.

The legend of Durandal reminds us that true legendary weapons are not just instruments of war, but carriers of values, stories, and meanings that transcend centuries. Although the final destiny of the sword remains shrouded in mystery, its indestructible spirit continues to live in every tale, in every reenactment, and in every heart that stirs upon hearing the echo of the olifant resonating in the Roncesvalles ravines.

The story of Roland and Durandal is, ultimately, a testament to the power of legend to shape our understanding of heroism, sacrifice, and transcendence.