What turned a simple steel blade into the emblem of an era? Imagine cobbled streets where fashion blends with the roar of battles, workshops where fire and hammer forge swords that speak of power and art. Renaissance swords are not just weapons: they are objects of prestige, dueling tools, and testimonies to a technology in full advance.

In this article, you will discover how swords evolved between the 15th and 17th centuries, what typologies dominated battlefields and cities, how metallurgy and aesthetics influenced them, and why today they continue to fascinating historians, fencers, and collectors. You will also find a clear chronology and comparative tables that will help you understand at a glance the technical and functional differences between the main families of swords.

A rebirth of the blade: context and transformation

The Renaissance was much more than an artistic movement: it was a technological revolution that permeated the forging of weapons. Improvements in steel production, knowledge about tempering, and the demand for protection in combat led to designs that sought a balance between cutting power, thrusting capability, and hand protection.

Thus, a typological diversity was born that includes the mandoble (great sword), the rapier, the estoc/stiletto, and regional variants such as the colichemarde. Each model responded to a need: to break formations, to duel, to defend the city, or to make one’s way through battlefields plagued by pikes and muskets.

Chronology of Renaissance Swords

The history of Renaissance swords has clear nodes in time that allow us to understand their technical and social evolution.

| Period / Date | Event / Description |

|---|---|

| 14th Century | Beginning of the development of the mandoble (Zweihänder/Bidenhänder/Bihänder) as an evolution of longswords. |

| c. 1445–1450 | First recorded appearance of the term “espada ropera” in Juan de Mena’s Coplas de la panadera. |

| 1474 | Citations in French documents of the term “rapière”. |

| 15th–16th Centuries | The mandoble gains importance and reaches its peak of popularity during the Renaissance. |

| 1525–1675 | Approximate period of maximum splendor of the rapier. |

| 16th Century | Widespread use of the mandoble in European armies (Holy Roman Empire, Italian city-states, Swiss Confederacy), highlighting the lansquenets; the rapier consolidates as a dueling sword and civilian accessory; appearance of the terciado in Spain; examples of flamberge blades in the Iberian Peninsula. |

| c. 1550–1620 | Spread of the hilted rapiers (complex guard of interwoven metal arches). |

| 1564 | Legislative documentation of the verdugo/verduguillo (narrow and ridged thrusting sword). |

| Mid-16th Century | The estoc is already considered a narrow-bladed and not excessively long sword. |

| Late 16th – Early 17th Century | Decline of the mandoble on the battlefield due to the effectiveness of firearms and tactical changes; hilted rapiers begin to be replaced by shell variants that protect the hand more. |

| Early 17th Century | Appearance of the colichemarde (or frantolpino) in the Iberian Peninsula; general tendency to narrow blades from the early 16th century to the early 17th century. |

| Not before 1620 / Mid-17th Century | Transition of shell-hilted rapiers to cup-hilted rapiers; some authors place the appearance of the cup not before 1620; its use spread throughout Spain and Italy and lasted until the 18th century. |

| Early 18th Century / 1715 | The rapier is progressively replaced by the lighter smallsword; by 1715 the smallsword had largely replaced the rapier in most of Europe, although the rapier continued to be used. |

| Modern Era | The mandoble experiences a revival in historical exhibition fencing and in the reconstruction of ancient combat techniques. |

| General Observation | Evolution from cutting-oriented weapons to thinner, thrust-focused blades, and transition from a predominantly military use to a growing role in dueling and as a fashion accessory. |

From Workshop to Field: Materials and Forging Techniques

The excellence of a Renaissance sword rests on three pillars: steel, tempering, and design. Master swordsmiths combined empirical knowledge and new techniques to achieve blades with the right balance between hardness (to maintain the edge) and toughness (to prevent breakage).

Fullers emerged as a solution to lighten the blade without compromising its strength. Hilts were wrapped in leather or wire, and pommels were carefully counterbalanced. Guards increased their complexity to protect the hand without sacrificing mobility.

Key Processes

- Steel selection and preparation: forged sheets and, occasionally, folding techniques.

- Blade forging: shaping by hammering and annealing.

- Tempering and drawing: critical steps to balance hardness and flexibility.

- Guard and hilt assembly: aesthetics and function merge into a single piece.

Mandoble vs. Rapier vs. Estoc: How to Choose According to Function?

To understand the logic of the Renaissance, it is convenient to compare the three great families: the mandoble (or zweihänder), the rapier (civilian/dueling sword), and the estoc/stiletto (specialized in piercing armor). Below is a table that synthesizes their attributes.

| Type | Main Use | Typical Length | Approximate Weight | Hand Protection | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandoble (Greatsword) | Battlefield, breaking formations | 1.2–1.8 m | 2–3.5 kg | Long guards, parrying hooks | Reach and cutting power |

| Rapier | Dueling and civilian use | 0.9–1.2 m | 0.9–1.4 kg | Loop guard, shell or cup | Versatility: cutting and thrusting |

| Estoc / Stiletto | Dueling and defense against armor | 0.8–1.1 m | 0.7–1.2 kg | Simpler or specific guards | Penetration and precision at the tip |

Usage Techniques and Fencing Schools

While the mandoble demanded strength, coordination, and two-handed handling techniques, the rapier required the development of sophisticated fencing schools such as the Verdadera Destreza in Spain. These schools designed geometrical methods for the control of space, time, and distance in dueling.

The estoc encouraged thrusting and precision practices, favoring more technical and rapid movements that sought seams in armor or exploited openings in the opponent’s defense.

The proliferation of fencing treatises in the 16th and 17th centuries allows us today to reconstruct historical techniques with rigor, benefiting both researchers and practitioners of historical fencing.

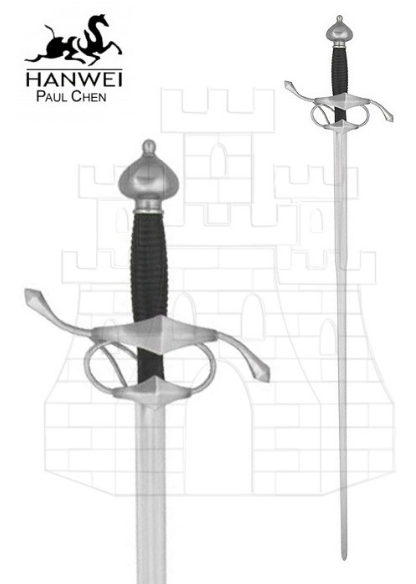

Guards: From Loop to Cup, the Hand on the Front Line

Hand protection was one of the visible revolutions in Renaissance swords. From the interwoven arches of the loop guard to the protective plates of the shell and the semi-sphere of the cup, the evolution was towards greater security without losing dexterity in fencing.

- Loop guard: complex and light, common in the first half of the 16th century.

- Shell guard: plates that partially enclose the hand, very popular in the late 16th century.

- Cup/bowl guard: semi-sphere that fully protects the hand, consolidated in the 17th century.

Symbolism and Aesthetics: A Sword is Also a Statement

In the Renaissance, the sword was a social accessory. It was decorated with damascening, gold and silver inlays, engravings, and ornate guards. Spanish blades from Toledo enjoyed fame for their quality, but manufacturing involved numerous specialized centers and guilds: blade masters, guard makers, gilders, and cutlers.

Scabbards and baldrics were carefully crafted. They produced pieces that, in addition to protecting the blade, projected the status of their bearer. Aesthetics and functionality coexisted in every sword, from the blade to the chape of the scabbard.

Variants and Technical Curiosities

Some variants deserve specific mention for their uniqueness:

- Flamberge: wavy blade that sought tactical and visual effects when cutting.

- Colichemarde: blade with a wide base and a sharpened tip, ideal for thrusting.

- Terciado: short and wide sword documented in Spain in the 16th century.

Practical Comparison: Which Sword Suits Each Scenario?

If you want to understand when each type was used, think about the context:

- Open field battle: mandoble to break formations.

- Duel in the city or court: rapier for its speed and style.

- Combat against armor: estoc or stiletto for their sharp point.

Each choice implied a combination of technique, aesthetics, and cost. It is no coincidence that the sword remained a symbol of status long after it lost its military primacy.

The Legacy: Historical Fencing, Replicas, and Preservation

Today, Renaissance swords live a second life in historical fencing and practical reconstructions. Functional and decorative replicas allow us to study handling, balance, and techniques that would otherwise remain confined to treatises and museums.

The conservation of original pieces requires knowledge: controlling humidity, preventing oxidation, and, in the case of functional replicas, maintaining the temper and sharpness safely.

Renaissance Swords in Catalog

If you are interested in seeing contemporary examples of replicas and pieces inspired by the Renaissance, below is a random selection of catalog items related to this category.

Summary Table: Technical Evolution by Centuries

| Century | Technical Trend | Dominant Typology |

|---|---|---|

| 14th Century | Transition from longswords to more specialized blades; beginnings of the mandoble. | Longsword / Mandoble in formation |

| 15th Century | Greater experimentation in guards and lengthening of hilts. | Mandoble and early rapiers |

| 16th Century | Stabilization of forms: rapier, estoc, flamberge variants; increase in professional production. | Rapier and mandoble |

| 17th Century | Narrowing of blades and appearance of the cup/bowl; military decline of great swords. | Evolved rapier, colichemarde |

Renaissance swords condense the tension between tradition and modernity: on the one hand, they preserve techniques inherited from the Middle Ages; on the other hand, they incorporate innovations that foreshadow the modern era. Their study reveals technological routes, social and aesthetic priorities, and a conception of combat in which personal technique and public symbology intertwine.

Therefore, when you hold a well-balanced replica or contemplate an old blade in a display case, you are holding a fragment of the Renaissance: a piece forged by human ingenuity, the desire for protection, and the will to leave a mark in history.

VIEW MORE RENAISSANCE SWORDS | VIEW LOOP HILT RAPIER SWORDS | VIEW CUP HILT SWORDS | VIEW FOILS