Have you ever wondered what secrets and battles the legendary swords of the Arab world hold? These were not mere weapons; they were extensions of the warrior, symbols of power, and works of art forged with a purpose. From the desert sands to the rich courts of Al-Andalus, four names resonate with an unbreakable force: the scimitar, the alfanje, the kabila, and the jineta. Each one, a vital chapter in the chronicle of war and cavalry. Get ready to discover the history, design, and legacy of these blacksmithing marvels that defined an era.

The Scimitar: The curved saber that dominated the East

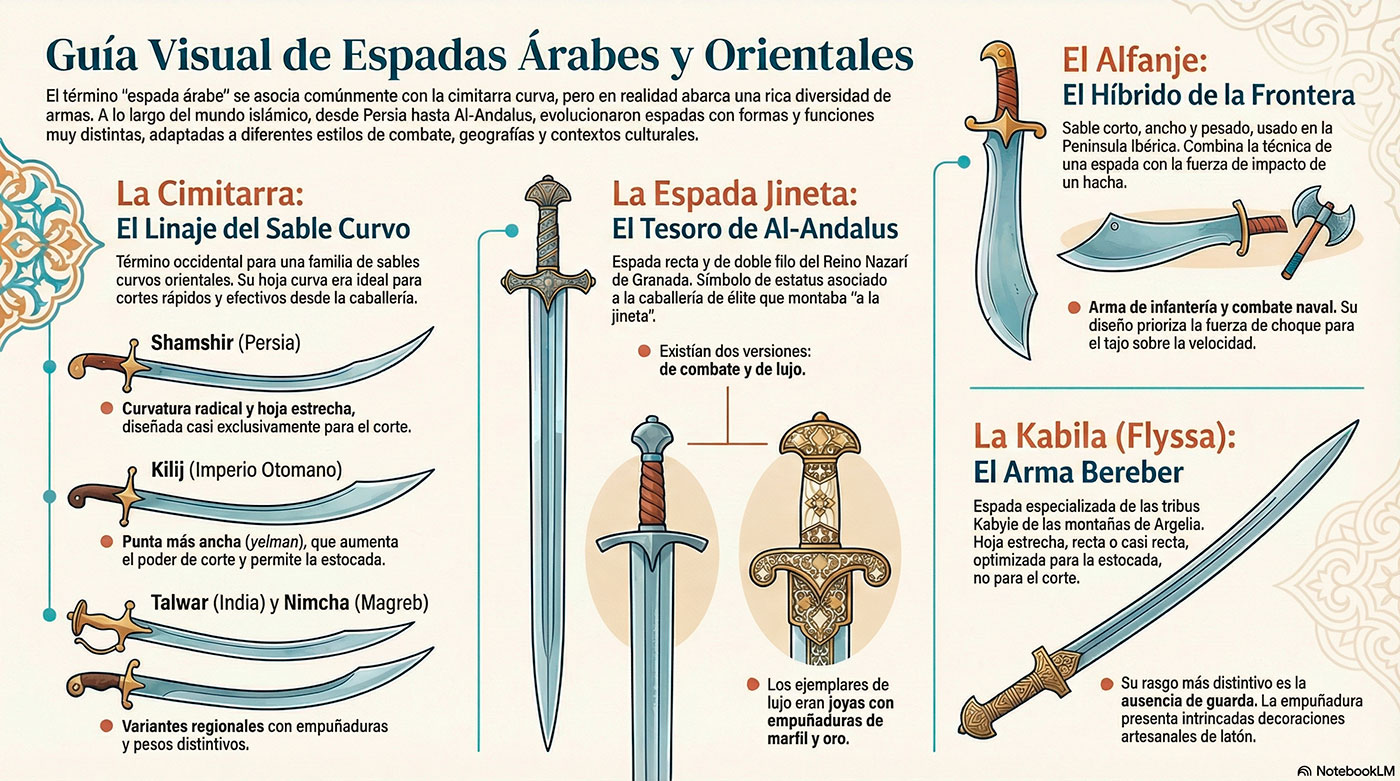

The scimitar, that evocative name adopted by the West to describe a set of curved Islamic sabers, is much more than a simple sword. It is an emblem, a legendary weapon that embodies agility and effectiveness in combat. With its long, thin, light, and markedly curved blade, designed for fluid cuts without getting stuck, the scimitar became the terror of its enemies, especially in the hands of cavalry. Its origin is traced to ancient Persia, around the 9th century, but its influence extended throughout the Middle East, adapting and evolving into various variants such as the Persian shamshir, the Ottoman kilij, or the Indian talwar.

The scimitar, that evocative name adopted by the West to describe a set of curved Islamic sabers, is much more than a simple sword. It is an emblem, a legendary weapon that embodies agility and effectiveness in combat. With its long, thin, light, and markedly curved blade, designed for fluid cuts without getting stuck, the scimitar became the terror of its enemies, especially in the hands of cavalry. Its origin is traced to ancient Persia, around the 9th century, but its influence extended throughout the Middle East, adapting and evolving into various variants such as the Persian shamshir, the Ottoman kilij, or the Indian talwar.

The Alfanje: The cutting force in the Iberian Peninsula

The alfanje, whose name derives from the Arabic “al-janyar” (dagger), is a hybrid sword forged in the cultural melting pot of the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean. Wider and heavier than the scimitar, it is distinguished by its pronounced curvature in the last third of the blade, optimized for delivering devastating cuts. This single-handed weapon, often fluted, became a formidable tool both in hand-to-hand combat and in more confined environments. Its legacy not only lies in its effectiveness but in how it represented the fusion of Arab and European warring styles, a true jewel of medieval and Renaissance blacksmithing.

The Kabila: A hybrid of design and functionality

Less known but equally fascinating is the kabila, or flyssa as the French knew it. This sword is a testament to the tribal Berber ingenuity of the Maghreb. Its secret? A hybrid design that takes the curved and long blade of the scimitar, but joins it to the characteristic hilt of the Nasrid jineta, which is narrower and flatter and often without a guard. With a narrow blade and a sharp point, the kabila was designed for thrusting, making it a lethal weapon in skirmishes in mountainous terrain. Its hilt, carved with intricate brass inlays, was not only functional but also a cultural hallmark of Kabyle craftsmanship.

The Jineta: Nasrid power and elegance

The jineta, the Nasrid sword par excellence, is the richest and most direct heritage of the Hispano-Arab panoply. Unlike its curved cousins, the jineta is characterized by a straight, double-edged blade, often with a central fuller up to the middle. But its true distinction lies in its magnificent hilt: bone-shaped, short, and designed for a single hand, with elegantly curved quillions that fall towards the blade. Beyond its effectiveness in the light cavalry that practiced the “monta a la jineta”, this sword was a symbol of extremely high status, richly decorated with filigrees, damascening, and niello in gold and silver, like the famous jineta of Boabdil, a war trophy that is preserved to this day.

Historical evolution of Arab and related swords

The history of bladed weapons in the Islamic world and the Iberian Peninsula follows two main lines: the development of the curved saber in the Middle East (scimitar and variants such as the shamshir) and the straight/slightly curved typology linked to Al-Andalus and the Nasrid Kingdom (the jineta and the alfanje). The following table chronologically orders the main milestones provided in the data, from the earliest testimonies to the colonial documentation of tribal weapons.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| Antiquity and origins | |

| 4th millennium BC | Documentation of straight swords in the Iranian Plateau (Persia), double-edged typology characteristic of pre-Persian cultures. |

| Early Middle Ages (7th–9th centuries) | |

| 631 AD | Arab conquest of Iran and introduction of Islam; previous Persian dynasties used straight, double-edged swords. |

| 7th century | Muslim culture gains cultural autonomy; slightly curved swords appear in northeastern Iran. |

| 8th–13th centuries | During the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate, curved swords begin to spread throughout the Middle East and North Africa. |

| 9th century | First documented examples of curved swords (scimitar) in the Abbasid era, especially in Khorasan; the scimitar already appears registered in the Middle East. |

| High Middle Ages (11th–14th centuries) | |

| 11th century | Slightly curved swords are integrated into official weaponry in Iran. |

| 12th century | Curved swords become the main weapon of the Iranian army; the Persian form called shamshir appears. |

| Second half of the 12th century | Saladin (Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn) is culturally associated with the scimitar as a representative weapon of the Muslim world in the Near East. |

| 10th century (Hispano-Arab context) | Documented presence of the “monta a la jineta” in Al-Andalus (testimonies such as the pyxis of al-Mughira) evidencing proper equestrian techniques. |

| 13th century | In the Peninsula, the jineta sword begins to be regularly used by Muslims; the alfanje has been used since the Middle Ages and persists until the Renaissance. |

| 1275 | May 14: landing of Emir Abu-Zayán with troops from the Banu-Merin (Zenete) in Tarifa, introducing the Zenete technique in peninsular warfare. |

| Late Middle Ages (14th–15th centuries) | |

| Early 14th century | The “monta a la jineta” is adopted by Christian frontier knights (e.g., Joan Ponçe de Còrdova, incursion of 1319). |

| 1330s | The Castilian royal court, including squires and young nobles, begins to adopt the jineta style and dress of Moorish influence. |

| 1340 | Documentation of jineta swords by Álvaro Soler del Campo; mural paintings of the Casita del Partal (Yūsuf I era) depict Nasrid weaponry. |

| 1348 | The Cortes of Alcalá de Henares record that “on the border with the kingdom of Murcia, everyone rides a la gineta”. |

| Mid/second half of 14th century | The jineta style consolidates in the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada; the ceremonial jineta attributed to Boabdil is dated to the time of Muḥammad V’s second emirate (1362–1391). |

| 1379 | Sumptuary legislation in the Cortes of Burgos exempts those “of the jineta of Andalusia”, allowing them to use swords and gilded elements. |

| 1390 | The Cortes of Guadalajara order the vassals of Andalusia and Murcia to ride “a la gineta”. |

| Late Medieval – Renaissance Transition (15th–16th centuries) | |

| 15th century | Christians adopt and manufacture the jineta sword. The origin of the Turkish sword kılıç is also related to this century. |

| 1431 | After the Battle of Sierra Elvira/La Higueruela, the African Zenete technique, accepted by Hispano-Muslims, is assimilated by Christian knights. |

| 1483 (April 20) | Capture of Boabdil in the Battle of Lucena; his ceremonial jineta sword was taken as a trophy. |

| 1487 | Additional record related to the capture of Boabdil’s sword in the Battle of Lucena (appears in sources as an event associated with the Nasrid fall). |

| 1492 | Conquest of Granada: end of the Nasrid sultanate and conclusion of the Hispano-Arab episode in the peninsula. |

| 1501 | Decree from the Catholic Monarchs allowing gilding of threads on jineta harnesses (regulation of sumptuary elements related to the jineta). |

| 1514 | The term “scimitar” appears in chivalric texts in Spain, linked to the Muslim imaginary; its massive use in the Peninsula is not corroborated until the 16th century. |

| Modern Age (16th–19th centuries) | |

| 15th–16th centuries (approx.) | Iranian swords gradually increase their curvature; they achieve great curvature and popularity in the 16th–17th centuries. The Persian shamshir became popular at the beginning of the 16th century. |

| 16th–19th centuries | Highly curved Persian swords (shamshir) continue to be the preferred type on the battlefields of Persian armies. |

| 16th–18th centuries | Possible influence of the Turkish yatagan saber on the weaponry of Kabylia (northern Algeria), initiating transformations in local blades. |

| 18th century | Probable emergence of the flyssa or kabila, the distinctive blade of the Kabyle (Kabylia), which will become a regional identity trait. |

| Contemporary Era and Colonial Documentation (19th–20th centuries) | |

| 1830–1962 | French colonial period in Algeria: the flyssa gains recognition and is documented by European collectors and ethnographers. |

- Antiquity and origins

-

- 4th millennium BC: Documentation of straight swords in the Iranian Plateau (Persia), double-edged typology characteristic of pre-Persian cultures.

- Early Middle Ages (7th–9th centuries)

-

- 631 AD: Arab conquest of Iran and introduction of Islam; previous Persian dynasties used straight, double-edged swords.

- 7th century: Muslim culture gains cultural autonomy; slightly curved swords appear in northeastern Iran.

- 8th–13th centuries: During the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate, curved swords begin to spread throughout the Middle East and North Africa.

- 9th century: First documented examples of curved swords (scimitar) in the Abbasid era, especially in Khorasan; the scimitar already appears registered in the Middle East.

- High Middle Ages (11th–14th centuries)

-

- 11th century: Slightly curved swords are integrated into official weaponry in Iran.

- 12th century: Curved swords become the main weapon of the Iranian army; the Persian form called shamshir appears.

- Second half of the 12th century: Saladin (Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn) is culturally associated with the scimitar as a representative weapon of the Muslim world in the Near East.

- 10th century (Hispano-Arab context): Documented presence of the “monta a la jineta” in Al-Andalus (testimonies such as the pyxis of al-Mughira) evidencing proper equestrian techniques.

- 13th century: In the Peninsula, the jineta sword begins to be regularly used by Muslims; the alfanje has been used since the Middle Ages and persists until the Renaissance.

- 1275: May 14: landing of Emir Abu-Zayán with troops from the Banu-Merin (Zenete) in Tarifa, introducing the Zenete technique in peninsular warfare.

- Late Middle Ages (14th–15th centuries)

-

- Early 14th century: The “monta a la jineta” is adopted by Christian frontier knights (e.g., Joan Ponçe de Còrdova, incursion of 1319).

- 1330s: The Castilian royal court, including squires and young nobles, begins to adopt the jineta style and dress of Moorish influence.

- 1340: Documentation of jineta swords by Álvaro Soler del Campo; mural paintings of the Casita del Partal (Yūsuf I era) depict Nasrid weaponry.

- 1348: The Cortes of Alcalá de Henares record that “on the border with the kingdom of Murcia, everyone rides a la gineta”.

- Mid/second half of 14th century: The jineta style consolidates in the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada; the ceremonial jineta attributed to Boabdil is dated to the time of Muḥammad V’s second emirate (1362–1391).

- 1379: Sumptuary legislation in the Cortes of Burgos exempts those “of the jineta of Andalusia”, allowing them to use swords and gilded elements.

- 1390: The Cortes of Guadalajara order the vassals of Andalusia and Murcia to ride “a la gineta”.

- Late Medieval – Renaissance Transition (15th–16th centuries)

-

- 15th century: Christians adopt and manufacture the jineta sword. The origin of the Turkish sword kılıç is also related to this century.

- 1431: After the Battle of Sierra Elvira/La Higueruela, the African Zenete technique, accepted by Hispano-Muslims, is assimilated by Christian knights.

- 1483 (April 20): Capture of Boabdil in the Battle of Lucena; his ceremonial jineta sword was taken as a trophy.

- 1487: Additional record related to the capture of Boabdil’s sword in the Battle of Lucena (appears in sources as an event associated with the Nasrid fall).

- 1492: Conquest of Granada: end of the Nasrid sultanate and conclusion of the Hispano-Arab episode in the peninsula.

- 1501: Decree from the Catholic Monarchs allowing gilding of threads on jineta harnesses (regulation of sumptuary elements related to the jineta).

- 1514: The term “scimitar” appears in chivalric texts in Spain, linked to the Muslim imaginary; its massive use in the Peninsula is not corroborated until the 16th century.

- Modern Age (16th–19th centuries)

-

- 15th–16th centuries (approx.): Iranian swords gradually increase their curvature; they achieve great curvature and popularity in the 16th–17th centuries. The Persian shamshir became popular at the beginning of the 16th century.

- 16th–19th centuries: Highly curved Persian swords (shamshir) continue to be the preferred type on the battlefields of Persian armies.

- 16th–18th centuries: Possible influence of the Turkish yatagan saber on the weaponry of Kabylia (northern Algeria), initiating transformations in local blades.

- 18th century: Probable emergence of the flyssa or kabila, the distinctive blade of the Kabyle (Kabylia), which will become a regional identity trait.

- Contemporary Era and Colonial Documentation (19th–20th centuries)

-

- 1830–1962: French colonial period in Algeria: the flyssa gains recognition and is documented by European collectors and ethnographers.

Clearing up unknowns about classic Arab and Nasrid swords

What is the main difference between the scimitar and the kabila?

The main difference between the scimitar and the kabila is that the scimitar is an Arab sword with a long, curved, light, and single-edged blade designed for cuts and thrusts, while the kabila is a hybrid that combines the curved and long blade of the scimitar with the characteristic hilt (handle) of the Nasrid jineta, which is narrower and flatter. In summary, the kabila has the scimitar blade but the design of the jineta’s handle.

The main difference between the scimitar and the kabila is that the scimitar is an Arab sword with a long, curved, light, and single-edged blade designed for cuts and thrusts, while the kabila is a hybrid that combines the curved and long blade of the scimitar with the characteristic hilt (handle) of the Nasrid jineta, which is narrower and flatter. In summary, the kabila has the scimitar blade but the design of the jineta’s handle.

What materials were used to make the hilts of the jinetas?

The hilts of jineta swords were made with high-quality and highly decorative materials, such as gilded bronze, silver, gold (in the form of filigree), ivory, and enamels.

How did Nasrid culture influence the design of the jineta?

Nasrid culture influenced the design of the jineta by developing a genuinely Nasrid type of sword, characterized by a straight, double-edged blade with a semicircular quillon towards the blade, a richly decorated hilt with Arabic inscriptions and damascening and niello techniques in gold and silver, reflecting a style of luxury and symbolism typical of this Muslim dynasty of the Kingdom of Granada. This sword was created for the light cavalry that used the technique of riding “a la jineta”, favoring agile and effective combat typical of Nasrid and Andalusian warfare.

The design of the jineta was an original product of Nasrid culture that combined functionality for light cavalry with exquisite artistic decoration inspired by Islamic aesthetics, evidencing Maghrebi and Eastern influences in addition to the Nasrid cultural identity.

What characteristics make the alfanje sword unique?

The characteristics that make the alfanje sword unique are its wide and curved blade, typically with an edge on one side and in some cases a false edge on the last third, which optimizes it for effective cuts. It is shorter and heavier than Eastern sabers, with a widening in the strong part of the blade near the tip, where the blow impacts. In addition, it usually has “S”-shaped quillons near the guard, and its design reflects a cultural mix between Muslim and Christian civilizations, especially in the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. This combination of form, functionality, and cultural heritage distinguishes it from other curved swords such as the falchion or the bracamarte.

In what historical contexts were Arab swords used?

Arab swords were primarily used in warlike and ceremonial historical contexts within Islamic and Arab societies from pre-Islamic times to the Middle Ages. They were common weapons among Arab warriors during the Islamic conquests and the Abbasid Caliphate (8th to 13th centuries), especially employed in horseback combat due to their design, whether with a straight or curved blade, such as the scimitar or the shamshir. In addition, they had great symbolic value as emblems of power, honor, and social status, and were used in ceremonies and ritual acts linked to Islamic culture. They were also part of the military tradition in regions that encompassed the Middle East, the Maghreb, Al-Andalus, and extended to Asia and Africa. Their use marked the style of combat and military culture of empires such as the Ottoman, Persian, and Mughal, and were preserved as symbols of lineage and family prestige.

From the desert to the Peninsula, from agility in riding to the sumptuousness of the court, Arab swords forged indelible legacies. Each of these four essential swords – the scimitar, the alfanje, the kabila, and the jineta – tells us a story of ingenuity, adaptation, and a martial art deeply rooted in their culture. They are the reflection of a time when metal and spirit united to write epics. Exploring their replicas is to touch a fragment of that greatness, connecting the present with the echo of ancient battles and ceremonies.

VIEW ALFANJES | VIEW ALL SCIMITARS | VIEW JINETAS SWORDS | VIEW KABILA SWORDS | VIEW MORE ARAB SWORDS