What hides the brief blade that accompanied the samurai in the dimness of corridors and in the ritual of honor? The Japanese wakizashi is not just a short sword; it is a symbol of status, a defense tool in enclosed spaces, and a piece of art forged between tradition and necessity.

A hook for history: the wakizashi in one sentence

Imagine a samurai’s waist at the dawn of the Edo period: next to the katana, a shorter blade shines, holding stories of combat, etiquette, and sacrifice. That blade is the wakizashi, the inseparable companion that defines part of the warrior’s identity.

Why is this sword of interest today? What will you learn here?

In this article, you will discover the origin and evolution of the Japanese wakizashi, its forging technique, its practical and symbolic function within the daishō, its variants and types, how to identify authentic pieces or well-made replicas, and what distinguishes a wakizashi from other Japanese short swords. You will also find comparative tables, historical images, and a clear chronological overview that will place you in each key era.

Wakizashi: history and evolution through time

The wakizashi, a traditional Japanese short sword, spans centuries of technical transformation and cultural significance: from its origins as a functional weapon to its consolidation as a symbol of samurai status and the art of forging.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| Early Origins | |

| 4th–5th Centuries A.D. | The oldest swords found in Japan, the chokutō, were straight and single-edged; they are considered forerunners of later short swords, including the wakizashi. |

| Heian Period | |

| 794–1185 | Beginnings of wakizashi history. Advances in Japanese metallurgy perfecting Chinese techniques; tachi (≈92 cm) were slender, curved, and forged with a hard surface and soft core. |

| Kamakura Period | |

| 1185–1333 | Considered the “golden age” of Japanese swords. The wakizashi consolidates in the samurai’s equipment; smiths perfect techniques such as inserting a low-carbon core. Blades from this period are especially valuable. |

| Nanbokuchō Period | |

| 1333–1392 | Due to invasions and military changes, tachi became larger and shorter swords like the tantō emerged for foot combat. The five great forging schools were established: Sōshū, Yamato, Bizen, Yamashiro, and Mino. |

| Muromachi Period | |

| 1336–1573 | The wakizashi’s form becomes standardized and acquires distinctive features. High demand leads to mass production which sometimes reduces quality. The uchigatana (~61 cm) manageable with one hand emerges; wakizashi blades from this era are highly valued. |

| Late Muromachi / Early Momoyama | |

| 1568–1603 | The uchigatana evolves into the daishō pair: katana (61–76 cm) and wakizashi (~46 cm). This set, worn at the waist, becomes a distinctive mark of samurai status. |

| Edo Period | |

| 1603–1868 | Peak of the wakizashi and daishō: the Tokugawa shogunate laws reserve their wearing to the samurai class, consolidating the wakizashi as a social emblem. A complex etiquette develops, manufacturing reaches an artistic zenith, and the weapon maintains tactical importance in confined spaces; during this era, Bushidō is codified. |

| 17th–19th Centuries (tsuba) | |

| 17th Century | Tsuba (guards) achieve great artistic value; they are characterized by more abstract trends. |

| 18th Century | Tsuba become more elaborate and begin to include artist signatures; from this century on they are also produced as collector’s items. |

| 19th Century | Tsuba are further refined and are mostly signed, consolidating their status as artistic and collectible objects. |

| Transition to the Modern Period | |

| Mid-19th Century | The wakizashi remains an essential part of the samurai’s equipment, despite social and military changes heralding modernization. |

| 20th Century | |

| After World War II | The manufacture of new swords in Japan was prohibited. |

| 1953 | The production of Japanese swords is re-legalized, though with strict government control and limits on the quantity registered forgers can produce monthly. |

| Present Day | |

| 21st Century | The traditional art of forging wakizashi continues alive and is protected as intangible cultural heritage; recognized masters transmit the craft. The wakizashi retains relevance in martial arts (e.g., Iaido), in collecting and museums, and in popular culture (contemporary art, manga, anime, and literature). |

- Key Periods

-

- Kamakura: technical consolidation and prestige.

- Muromachi–Edo: standardization, daishō, and artistic heyday.

- 19th–20th Centuries: transition and modern regulation.

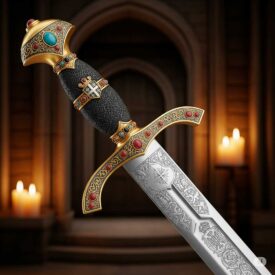

Anatomy of the wakizashi: each part with purpose

A wakizashi is made up of elements that are both functional and symbolic. Understanding its anatomy helps to recognize quality and authenticity: the blade (tō), the hilt (tsuka), the guard (tsuba), the collar (fuchi), the pommel (kashira), and the scabbard (saya). Each piece may bear ornamentation indicating lineage, forging school, or status.

The blade: between technique and beauty

The wakizashi blade was traditionally forged from tamahagane, a steel that, through repeated folding and differential hardening, offered a balance between sharpness and resilience. The hamon (temper line) was not only functional but also an aesthetic signature of the master smith.

The tsuba and the finish: identity of the bearer

The guards (tsuba) can be sober or exuberant. Sometimes they were true works of art with inlays and motifs that told stories of the clan or the individual. A signed tsuba increased the value of the piece.

Traditional forging technique: basic steps and their meaning

The traditional process is a ritual in itself: selection of tamahagane, forging in charcoal, folding to homogenize carbon, joining layers, forming the curvature (sori) by water quenching, and finishing with sanding and polishing that reveals the hamon. Each stage influences the handling and durability of the blade.

What differentiates a good wakizashi?

- Proportion between edge and core that allows flexibility without fragility.

- Clear and uniform hamon, indicative of controlled quenching.

- Sanding finish (togi) that respects the original geometry of the blade.

- Worked fittings and traditional materials in the tsuka and saya.

Wakizashi in practice: tactical, ceremonial, and daily uses

The wakizashi had diverse roles: secondary weapon in combat, defense indoors where the katana was impractical, tool for the seppuku ritual, and object for daily etiquette. Its length allowed for quick drawing and maneuvers in enclosed spaces that would be unfeasible with the katana.

On the battlefield and at home

In formations and open combat, the katana dominated; in hallways, rooms, or very close encounters, the wakizashi offered an advantage due to its maneuverability. In addition, the custom of leaving the katana at the entrance of buildings meant the wakizashi remained close at hand even when the katana was not.

Variants, lengths, and typologies

Although the general definition places its length between 30 and 60 centimeters, there are nuances: the ko-wakizashi (longer, closer to the katana), the o-wakizashi (closer to the tanto), and intermediate pieces that respond to specific schools or uses. The curvature, thickness, and cross-section vary according to the era and forging school.

| Type | Blade length (approx.) | Primary use | Distinctive feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ko-wakizashi | ~50–60 cm | Complement to the katana, greater reach than the standard wakizashi. | More curvature and greater length. |

| Standard Wakizashi | ~30–46 cm | Defense in enclosed spaces and secondary weapon. | Balance between handling and cutting power. |

| O-wakizashi / Tanto | <30 cm | Cutting and stabbing at very short distances, rituals. | Less curvature, sometimes similar to a dagger. |

- Types in motion

-

- Ko-wakizashi: closer to the katana in length.

- Standard Wakizashi: the most versatile and recognized.

- Tanto / O-wakizashi: short blade for precise cuts and rituals.

How to read a wakizashi: marks, signature, and materials

Inscriptions on the nakago (tang) reveal the forger and, sometimes, the date and school. The nakago-ji and the signature (mei) help authenticate pieces. The presence of tamahagane and the folding technique are signs of traditional forging, although excellent modern replicas with convincing finishes exist today.

Signs of authenticity

- Mei consistent with the indicated school and era.

- Natural patina on the nakago commensurate with age.

- Hamon and hada (steel texture) consistent with traditional techniques.

- Fittings signed or with craftsmanship in accordance with the period.

Practical comparison: wakizashi vs katana vs tanto

Understanding the practical differences allows one to appreciate why each sword has its place in samurai culture and modern martial practice.

| Aspect | Wakizashi | Katana | Tanto |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 30–60 cm | ≥ 60 cm | < 30 cm |

| Primary Use | Enclosed spaces, secondary | Open and offensive combat | Ritual and fine stabbing |

| Handling | Fast and maneuverable | Greater momentum and reach | Precision and thrust |

| Symbolism | Status and daily duty | Honor and military power | Sacredness and ceremony |

- Mobile Comparison

-

- Wakizashi: versatile indoors.

- Katana: dominant in the open field.

- Tanto: designed for short cuts and rituals.

Replicas, practice, and collecting

Contemporary interest in the wakizashi is manifested in decorative replicas and blades for practice (iaido, battōjutsu). Collector valuation rests on the forging technique, the origin of the tamahagane, and the documentation accompanying the piece.

Related services and products

If you are interested in experiencing the feel of an authentic wakizashi or a well-made replica, there are options for martial practices and decorative pieces. Remember that regulations and ethics surrounding Japanese swords vary by country, and that the preservation of traditional technique is a cultural practice that deserves respect.

Care, conservation, and safety

A wakizashi requires maintenance: regular cleaning, rust prevention, proper storage in the saya, and inspection of the fittings. Learn to draw and handle with respect; safety is the responsibility of the bearer and a reflection of the code that historically accompanied these blades.

Clearing doubts about the wakizashi and its role in samurai culture

The main difference between the wakizashi and the katana is the length of their blades: the katana has a long blade (generally more than 60 cm), designed for longer-range and more powerful attacks, while the wakizashi has a shorter blade (between 30 and 60 cm), ideal for close combat and fast, precise movements. This difference influences their tactical use: the katana is the primary weapon for open combat, and the wakizashi functions as a secondary weapon for confined spaces and personal defense situations. Additionally, the katana has a more pronounced curvature and a thinner blade, while the wakizashi is more compact and robust.

In the Edo period, the wakizashi was manufactured using highly refined traditional Japanese techniques that included the use of tamahagane, a pure steel obtained from iron sand, and a process of repeated forging and folding to achieve high quality and strength in the blade. The blade structure featured a slight curvature (sori) and differential tempering that hardened the edge (hamon) to offer a sharp cutting edge and an elastic back. The blade generally had a rhomboidal section with a groove (hi). The handle (tsuka) was covered with ray skin (samegawa) and wrapped in silk (ito) to improve grip. The guard (tsuba) was smaller than on the katana and often artistically decorated, while the scabbard (saya) was made of magnolia wood and lacquered with various techniques, from simple to elaborate with gold powder motifs (maki-e). The mounting (koshirae) involved the collaboration of various artisans specialized in their respective parts, making the wakizashi both a functional tool and a work of art, as well as a regulation sword for the samurai class under the strict rules of the Tokugawa shogunate.

The wakizashi had fundamental ceremonial significance in samurai culture, being a materialized symbol of the samurai’s soul, moral integrity, and inner strength within the strict feudal Japanese social order. Its handling in ceremonies followed a precise protocol that expressed respect and pacifism, and it played a central role in the seppuku (ritual suicide) ritual, where it was used to restore the samurai’s honor. Furthermore, along with the katana, it formed the daisho, which represented the bearer’s social status and ethical values according to the Bushidō code. Therefore, the wakizashi was not only a practical weapon but an object charged with spiritual and social meaning.

The forging techniques used to create a traditional wakizashi include the preparation and selection of tamahagane steel, which is heated to approximately 1,300 °C and subjected to multiple foldings (up to 15 times) to homogenize the carbon and eliminate impurities, generating more than 30,000 layers. Then, the smith models the blade with controlled hammer blows at various temperatures, specifically defining the kissaki (tip) and the edge, through repeated cycles of heating and working until the desired shape and characteristics are achieved.

Additionally, a distinction is made between hard outer layers (kawagane) and a softer core (shingane) to balance strength and flexibility. Specific traditions, such as the Yamato school, apply particular folding and tempering techniques that generate unique patterns in the steel (masame-hada) and a characteristic curve in the blade (torii-zori). The tempering and forging are refined to produce a clear and controlled hamon, which highlights the quality and function of the blade.

In summary, the process includes: selection and refining of tamahagane, repeated heating and folding, shaping with a hammer, specialized tempering, and finishing to achieve the characteristic shape, edge, and mechanical properties of the wakizashi. This method combines traditional craftsmanship and metallurgical knowledge aimed at a balance between hardness and flexibility essential for the sword’s functionality.

The wakizashi was used in the seppuku ritual as the weapon to perform the act of ceremonial disembowelment. The samurai used this short sword to make a cut in his abdomen, generally from left to right, in a movement that had to be deep to cause rapid death by blood loss. In the ritual, the wakizashi was placed on a stand, and after preparations such as a cold bath, white attire, and writing a farewell poem, the samurai performed the cut with this sword. Subsequently, an attendant (kaishakunin) completed the act by decapitating the samurai to prevent prolonged suffering. Although the tanto or katana were sometimes used, the wakizashi was common due to its suitable size for this ritualistic purpose.

How to interpret historical and sentimental value

Not all value is measured in antiquity or raw material. Many wakizashi tell personal stories: family donations, ceremonies, local battles, or changes in social status. Learning to read the patina, marks, and documentation will allow you to better understand the piece in front of you.

The wakizashi in contemporary culture

From cinema to manga, the wakizashi appears as a symbol of tradition and character. In modern martial arts, its presence recalls the technical continuity between past and present, and its aesthetics inspire contemporary ceramists, jewelers, and designers.

References for further study and advancement

If your curiosity pushes you beyond this article, seek out studies on Japanese forging, catalogs of smithing schools, and the bibliography of the Kamakura–Edo periods. Studying the social context and technical evolution will allow you to understand why the wakizashi is much more than a short blade.

The Japanese wakizashi is presented as the blade that embodies samurai duality: utilitarian and ceremonial, warlike and symbolic. By exploring its anatomy, technique, and history, we understand why a short sword can carry centuries of meaning and human mastery.

VIEW DECORATIVE WAKIZASHIS | VIEW FUNCTIONAL WAKIZASHIS | VIEW OTHER JAPANESE SWORDS