In the silence of a park at dawn, the tip of the Jian describes a line connecting body, intent, and air. Which weapon would you choose to feel that union? This article explores the most relevant Chinese weapons for Tai Chi and Kung Fu, their history, uses, and how to integrate them into practice, with images and classic references naturally distributed.

Chinese weapons did not emerge overnight: they evolved alongside dynasties, agriculture, and philosophy. Below is a synthesized chronology of their historical development and use, designed to understand how they came to the internal and martial arts we practice today.

| Type | Approximate Period | Origin/Context | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Straight sword (Jian) | Yin–Han Dynasties (millennia B.C. – 1st century B.C.) | Aristocracy and Taoism; symbol of status and spirituality | Institutionalized in internal arts like Tai Chi and in Kung Fu forms |

| Saber (Dao) and variants | Imperial periods; consolidation in the Middle Ages | Agricultural and military influence; variants for cavalry and militias | Forms the cutting repertoire of Kung Fu, popular and military weapons |

| Spear (Qiang) and halberd (Guandao) | From antiquity to the medieval era | Long field and formation weapons | Basis of reach techniques; widely used in Shaolin training |

| Staff (Gun) and club | Continuous throughout history | Rural tool adapted as a weapon | Pedagogical weapon: easy progression from empty hand |

- Straight sword (Jian)

-

- Period: Ancient Dynasties (Yin–Han).

- Origin: Noble and ritual weapons, associated with power and spirituality.

- Use: Thrusting and subtle techniques; essential in Tai Chi.

- Saber (Dao)

-

- Period: Extended use in imperial eras.

- Origin: Derived from agricultural tools and cavalry tactics.

- Use: Cutting and force, very present in Kung Fu.

Evolution of Chinese Weapons: From Jian to Dao

| Period/Date | Event or Main Weapon |

|---|---|

| Ancient Periods and the Bronze Age (c. 13th Century B.C. – 476 B.C.) | |

| c. 13th Century B.C. | Initial appearance of the **Jian** (straight double-edged sword). |

| Zhōu Dynasty (Western Zhou, 1046-781 B.C.) | The **Jian** is used as a short, secondary military weapon (28-46 cm blade). |

| Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 B.C.) | The Jian reaches up to 56 cm of blade. Legendary swords like the **Longyuan** (later Longquan) are forged. |

| Warring States Period (~300 B.C.) | The technology of bronze swords (Jian) reaches its peak. |

| Qin and Han Dynasties (221 B.C. – 220 A.D.) | |

| 221 B.C. (Qin Dynasty) | Swords are forged to symbolize imperial power (**dingqin**). |

| Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 220 A.D.) | The **Dao** (single-edged saber) appears in the military sphere. |

| Mid-Han Dynasty | The **Dao** replaces the **Jian** as the main military weapon due to its greater robustness and less need for training. |

| End of the Three Kingdoms Period | The abandonment of the use of the **Jian** in the military field in favor of the **Dao** is consolidated. |

| Post-Jin (Since the Jin Dynasty) | |

| Jin Dynasty (265-420 A.D.) | The **Jian** ceases to be used on the battlefield. |

| Post-Jin | The **Jian** begins to be used as a symbolic or ritual weapon. |

| Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.) | The **Jian** is categorized as one of the “three great arts” (art, elegance), while the hegemony of the **Dao** in the military continues. |

| Song Dynasty (960-1279) | The **Dao** establishes a great diversity of forging styles, including the **Zhanmadao** (for cutting horses) and the **Yanmaodao** (transitional curved saber). |

| Yuan Dynasty (Mongol) (1271–1368) | Mongol influence on the development of the Chinese saber, adapting it for cavalry. |

| Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368 – 1912 A.D.) | |

| Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) | The **Jian** declines militarily, but revives as a refined weapon, associated with scholars and self-defense. Guides on the **Dao** saber (**Liuyedao**, **Changdao**) are published. |

| Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) | The **Dao** maintains its military and civil functionality. The **Jian** continues to be used in designs until the 17th century. |

| Modern Era (1911 – Present) | |

| Republican Era (1911-1949) | Revival of the use of the straight sword for self-defense; abundant material on martial arts (**Qingping Jian**) is published. |

| 1965 (December) | Discovery of the sword of **Goujian**, a bronze artifact more than 2500 years old. |

| Present | Both the **Jian** and the **Dao** continue to be used in Chinese martial arts training, such as Taijiquan. |

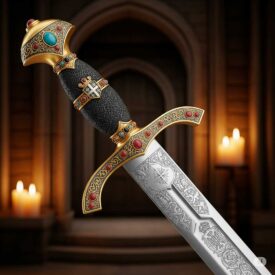

Essential Arsenal: Jian, Dao, Dadao and more

Knowing the purpose of each weapon helps you choose the most suitable for your practice. Here I gather practical, technical and cultural descriptions of the most representative weapons.

Jian — the straight sword

The Jian is the straight-bladed white weapon par excellence of the Chinese people. It is a long, double-edged sword with practically no guard. It is one of the four great weapons of Chinese Martial Arts, known in this group as the “Gentleman of all weapons”. The Jian is used in numerous martial arts, such as Kung-fu or Wu-Shu, which stand out for their fame and for the skill in handling the straight sword or Jian. This weapon is also used in Tai-Chi Chuan.

Dao and Dadao — the edge of popular and martial practice

The Dao is a curved, single-edged Chinese saber and is one of the four great weapons of Chinese Martial Arts. It is a cutting weapon, which comes, among others, from the Japanese katana. Its shape and dimension have varied throughout the centuries, giving rise to different types of Dao; Liu Ye Dao, Yao Dao, Zhan Ma Dao and Yan Ling Dao. The martial art in which the Dao is most used is Vovinam Viet Vo Dao.

The Dadao is one of the variants of the Dao or Chinese saber. This weapon, which is based on agricultural knives, was used by civil or revolutionary militias and common people. It is a saber with a large blade that can measure between 60 cm and 90 cm. The length of the hilt could be for one and a half or two hands. Although it was not a very sophisticated weapon, its blade had great cutting power and was lethal for adversaries without much military preparation.

Long weapons and reach tools

In Kung Fu and some forms of Tai Chi, long weapons such as the spear (qiang), the staff (gun), and the halberd (guandao) allow practitioners to work on reach, timing, and body coordination. Their study improves distance perception and control of the center of gravity.

Fan and soft weapons

The fan is distinctive in some Tai Chi forms; it aids fluidity and expressiveness. Originally, some fans incorporated cutting elements, although in modern practice, light materials and technical aesthetics prevail.

Double weapons and Kung Fu specialties

Styles like Shaolin incorporate double weapons (shuangdao, shuangchui) that elevate coordination and technical complexity. Working with two weapons simultaneously improves spatial vision and rhythm.

Training: how and when to introduce weapons

Learning is progressive: first master empty-hand forms, then the saber for its simplicity, and later, the sword or spear according to your style. The practical rule is to integrate weapons when postural control and an understanding of the rhythm of Tai Chi or Kung Fu already exist.

- Initial level: Staff or light saber, emphasis on coordination.

- Intermediate: Jian (sword) and spear, work on precision and reach.

- Advanced: Double weapons, fast forms, and martial application.

Chinese Replicas You’d Want in Your Collection

If you’re looking to try different weapons in your training, replicas and accessories help you get familiar with the weight and length without sacrificing safety. Below are relevant products from the related category.

Dadao Swords

Dao Swords

Jian Swords

KungFu Swords

Quick Comparison: Choose According to Objective

This table helps you decide based on your objective: health, technical aesthetics, or martial application.

| Weapon | Length (approx.) | Blade type | Main improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jian | 70–110 cm | Double-edged | Precision, energetic control |

| Dao / Dadao | 60–90 cm | Single-edged (curved) | Cutting power, dynamic coordination |

| Qiang (spear) | 200–300 cm | Point | Reach, thrust, and footwork |

| Gun (staff) | 150–200 cm | Non-cutting | Technical base, versatility |

- Jian

-

- Length: 70–110 cm

- Use: Health, forms, fine technique

- Dao / Dadao

-

- Length: 60–90 cm

- Use: Martial training and cutting

Practical Connection: Exercises and Quick Tips

- Exercise 1: Shadow with Jian, 5 minutes focusing on the tip and breathing.

- Exercise 2: Controlled cut with Dao, 3 sets of 10 repetitions to work on waist rotation.

- Tip: Keep the sword light in hand; in Tai Chi, relaxation overcomes force.

Historical References and Notes on Materials

Traditional weapons were constructed according to function: tempered blades for sharpness, reinforced handles for long weapons, and lightweight materials for exhibition weapons. In modern replicas, a balance between aesthetics, safety, and handling is sought.

Context and Nuances: The Case of the Kyoketsu Shoge

The old article mentions the Kyoketsu Shoge, a blade linked to the Japanese ninja tradition with a chain and rings. Although it is not part of the traditional Chinese arsenal, its mention here serves to compare weapon philosophies: adaptability and the use of flexible elements appear in different martial cultures.

Clarifying Doubts About Sword Handling in Tai Chi and Kung Fu

What are the main differences between sword handling in Tai Chi and Kung Fu?

Main Differences in Sword Handling Between Tai Chi and Kung Fu

Approach and Purpose of Handling

- Tai Chi with sword (Jian): Focuses on smooth, fluid, and sustained movements, with emphasis on precision, intent, and internal balance. The handling is elegant, with asymmetrical movements that seek harmony between body and sword, avoiding muscle tension and prioritizing concentration on the tip of the weapon. The practitioner seeks relaxation, mind-body connection, and subtlety in movements, reflecting the philosophical principles of balance and calm of Tai Chi.

- Kung Fu with sword: Presents a more martial and external approach, characterized by speed, strength, and aggressiveness in attacks and defenses. Movements are usually faster, more vigorous, and direct, seeking efficiency in the application of cutting and thrusting techniques. Handling requires greater use of the body, especially the waist and torso, to generate power and speed in actions.

Techniques and Physical Characteristics of the Weapon

- Tai Chi: Uses a straight sword (Jian), light, flexible, and double-edged. The grip is relaxed, and movements are primarily executed with the wrist, allowing for a large number of elegant variations and rhythm changes. The sword should not touch the body, and attention is focused on the tip.

- Kung Fu: Employs both the straight sword and the wide saber (Dao), depending on the style. In general, the saber is heavier, single-edged, and curved, designed for powerful cutting. Movements are usually broader and more energetic, executed with the entire arm, and focused on the effectiveness of the attack.

Spirit and Application

- Tai Chi: Prioritizes sensitivity, body awareness, and harmony, transforming the practice into a meditative experience and internal growth, beyond martial application.

- Kung Fu: Emphasizes physical dexterity, combat capability, and adaptability to different confrontation situations, with training that seeks efficiency and preparation for real combat.

In summary, Tai Chi with a sword stands out for its elegance, fluidity, and internal focus, while Kung Fu with a sword is distinguished by its power, speed, and direct martial application. Both disciplines share roots but differ notably in technique, spirit, and purpose.

What weapons are most common in Tai Chi Chuan practice?

In Tai Chi Chuan practice, the most common weapons are:

In Tai Chi Chuan practice, the most common weapons are:

- Sword (Jian): A straight, double-edged sword used for strategic thrusting and cutting techniques. It is considered a noble and spiritual weapon, associated with fire and lightning.

- Saber (Dao): A curved weapon used for cutting and striking techniques. In ancient China, it was associated with warfare.

- Spear: Although not as commonly associated with Tai Chi Chuan as the sword and saber, it is used in some traditional forms.

Additionally, the fan is also used in some variants of Tai Chi Chuan, especially in more modern styles or competitions.

How are weapons integrated into the daily Tai Chi practice routine?

Weapons in the daily Tai Chi routine are integrated after mastering basic empty-hand forms, generally after the 24 or 32 movement sequence itself. Working with weapons—such as the saber, sword, spear, staff, fan, or “whip stick”—is not merely a series of external techniques, but a natural extension of the body, where the weapon becomes a prolongation of the hand and Qi.

In daily practice, the routine is articulated in smooth and continuous circles, integrating body movements with those of the weapon to achieve harmony and energetic fluidity. Weapon training aims to deepen coordination, balance, sensitivity, and internal connection, and requires the practitioner to already have basic body control and some experience in empty-hand forms.

In summary, the integration of weapons into daily Tai Chi practice implies:

- Preparation Level: Only after mastering basic forms does weapon work begin, to ensure that the body and Qi flow correctly towards the instrument.

- Progression: It usually starts with the saber, due to its simplicity, and then progresses to the sword or spear, depending on the style and tradition.

- Internal Focus: Weapon handling is not just physical, but energetic; the practice seeks for the weapon to be an extension of the hand and Qi, not just an external adornment.

- Types of Weapons: Each weapon (saber, sword, spear, staff, etc.) has its own sequence and purpose, although all maintain the philosophy of Tai Chi: fluidity, softness, and mind-body connection.

Thus, the weapon routine becomes a logical and enriched evolution of daily practice, deepening the principles of Tai Chi and offering new dimensions of training.

What specific benefits do weapons provide in Kung Fu practice?

Weapons in Kung Fu practice provide specific benefits such as developing reach, timing, and precision, skills that transfer even to unarmed combat. Furthermore, training with weapons improves motor coordination, dexterity, body control, and biomechanical understanding of movements in combat. This training also strengthens discipline and self-control, promoting personal and ethical development, moving away from violence to channel energies positively. Finally, the study of weapons helps to understand specific physical and tactical characteristics, enriching the practitioner’s physical and mental conditioning.

Are there Tai Chi styles that do not use weapons?

Yes, there are Tai Chi styles that do not use weapons. Traditional practice includes both empty-hand forms (without weapons) and forms with weapons (saber, sword, staff, etc.), but the best known and most widespread basis worldwide is empty-hand practice, through sequences of movements called “empty-hand forms”. These forms are the main focus for most practitioners, regardless of the style (Chen, Yang, Wu, Sun, or Hao), and constitute the core of Tai Chi learning and transmission in most schools.

Weapon forms are complementary and are not necessary for the fundamental development of the art. In many academies and groups, teaching is limited to empty-hand forms, especially in contexts oriented towards health and well-being. Therefore, it is possible to practice Tai Chi without ever using weapons.

In closing, remember that each weapon tells a story: the Jian speaks of precision and spirit, the Dao of cutting and power, the spear of reach, and the staff of teaching. Choose according to your objective and progress with patience; true mastery is born from constancy and understanding the body as an instrument.

VIEW MORE CHINESE SWORDS | VIEW DADAO SWORDS | VIEW DAO SWORDS | VIEW JIAN SWORDS | VIEW KUNGFU SWORDS