Have you ever wondered how the head of a noble or a peasant in the Middle Ages revealed their entire world? Beyond simple protection from the sun or cold, medieval hats were a canvas of social status, profession, and the intricate fashions of the era. For the historical reenactor, understanding this diversity is key to fully transporting oneself to a vibrant past. In this article, we will unveil the mysteries of medieval headwear, exploring its origins, evolution, and the symbolism that turned them into authentic declarations of identity.

Caps, hats, and headwear: evolution in the Middle Ages

Head covering was a constant social and functional requirement in the Middle Ages for both sexes. The following chronology summarizes, by periods, the appearance and transformation of caps, hats, and their predecessors (tocas, bonnets, hoods, etc.) according to available sources.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| High Middle Ages (5th–11th Centuries) | |

| Merovingian Period (481–752) | There is no record of specific male headwear. Married women gathered their hair in a bun and single women wore it loose; they possibly used hairpins. |

| Carolingian Period (752–987) | Men: the tunic eventually incorporated a hood. Women: headwear with pearl threads or precious stones appeared; the veil solidified as an essential element of decorum. |

| High and Late Middle Ages (12th–15th Centuries) | |

| Male Headwear | |

| 13th Century | – The coif (fine cloth to gather hair) was adopted as a civil and ornamental garment; it was worn alone or under other headwear. – The bonnet/capiello (rigid or semi-rigid headwear) was used by privileged classes; its term encompassed several types. It was inspired by cylindrical helmets from the early 13th century. – The capiello of the beret type (fitted or loose) appeared and was worn by clerics, doctors, and military orders. – Also appeared the cale (fitted coif), the casque (hemispherical cap), and the birretes (flexible caps). – Hats (with a brim) were unusual among the high nobility. |

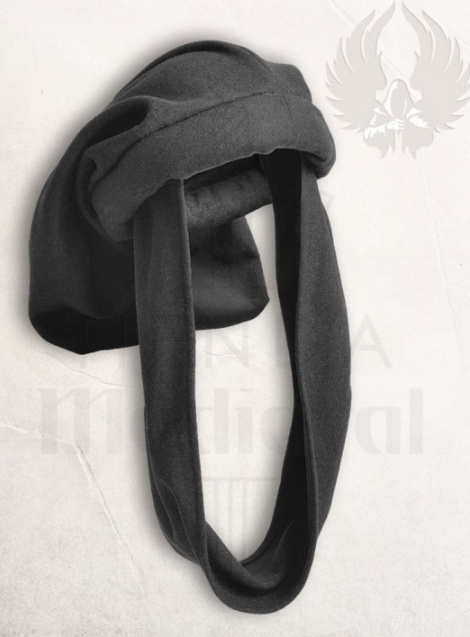

| Late 12th Century – 14th Century | – The hood became a characteristic accessory to cover the head. – In the late 12th century, the hood separated from the garment and was worn as an independent accessory with a short pelerine. – In the 14th century, a long band called cornette or coquille that hung was added to the tip. – Towards the end of the 14th century, the gaban emerged, which could incorporate a hood. |

| 15th Century | – Evolution of the caperuza: sometimes rolled over the opening of the visagière; the cornette was rolled forming a turban. – The formed caperuza became a true hat (with a brim). – The bourrelet (roll) appeared and, around 1460, the cramignolles (headwear with cut edges). – Throughout the 15th century, felt and beaver hats became popular with multiple shapes (peaks, round or bulging crowns, inverted cones) and various types of brims. |

| Female Headwear | |

| 12th–13th Centuries (Hispanic Kingdoms) | – Social imperative to wear the head covered (capite velata). – Tocas (simple veils) were common; the word «toca» spread throughout Europe. – The almízar (a kind of turban with a chin strap), possibly due to Andalusian influence, was used by the nobility. – Women’s hats did not appear until the second half of the 13th century and were reserved for travel or outdoor activities. – The crespina (hairnet) was used from the Middle Ages and at the beginning of the Renaissance. |

| Second half of the 14th Century – early 16th Century | – The corniform headpiece (horn-shaped) emerged in the peninsular north; the oldest representations are dated to the northern plateau (Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos, ca. 1384–1388). – It spread in the 15th and early 16th centuries over a wide area between Galicia and Aragon. – Burgundian hennins and extreme variants (pointed bell-tower type headwear) appeared around 1440, which could reach up to 1.2 m in some cases. – In the 15th century, female headwear became complex technical structures: tall, conical, with veils and nets. |

| Transition Middle Ages → Modern Age (Late 15th – early 16th Century) | |

| Late 15th Century | Existence of the guild of bonnet makers, clearly differentiated from hat makers and toca makers (manufacturers of tocas/veils). |

| Turn of the 15th–16th Century (c. 1500) | The cap is born: a soft, flexible, rounded and flattened headpiece, with a folded brim; it begins to be imposed in civil attire. |

| Early 16th Century (ca. 1500–1525) | The bonnet was still used in courtly circles, but began to be replaced by the cap and the hat in civil fashion. |

| First quarter of the 16th Century | Corniform headwear continued to be represented in areas such as Ezcaray and Mondoñedo. |

| After 1531 | The cap and the hat (the latter with a brim) were consolidated as the main male head accessory in the civil sphere, replacing the bonnet; the cap tended to reduce its size. |

| Second quarter of the 16th Century onwards | The bonnet remained reserved for specific areas (ecclesiastics, students, bachelors, doctors) and lost its generalized use. |

| Fundamental Distinction (summary note) | |

| Cap vs. Hat / Bonnet | – A cap is a soft garment, without a brim or visor. – A hat is defined by having a brim around the crown; in the 15th century, hoods already converted into hats appeared and felt and beaver hats with brims became popular. – The bonnet (capiello) is traditionally a rigid or semi-rigid cap of medieval heritage; over time it was limited to ecclesiastical and academic uses. |

- High Middle Ages (5th–11th Centuries)

-

- Merovingian Period (481–752): No record of specific male headwear. Married women gathered their hair in a bun and single women wore it loose, possibly using hairpins.

- Carolingian Period (752–987): Men: the tunic eventually incorporated a hood. Women: headwear with pearl threads or precious stones appeared; the veil solidified as an essential element of decorum.

- High and Late Middle Ages (12th–15th Centuries)

-

- Male Headwear (13th Century):

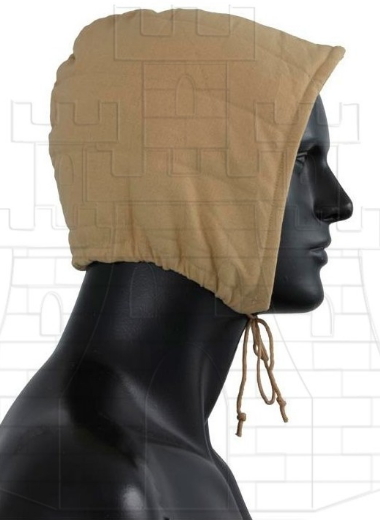

– The coif (fine cloth to gather hair) was adopted as a civil and ornamental garment; it was worn alone or under other headwear.

– The bonnet/capiello (rigid or semi-rigid headwear) was used by privileged classes; its term encompassed several types. It was inspired by cylindrical helmets from the early 13th century.

– The capiello of the beret type (fitted or loose) appeared and was worn by clerics, doctors, and military orders.

– Also appeared the cale (fitted coif), the casque (hemispherical cap), and the birretes (flexible caps).

– Hats (with a brim) were unusual among the high nobility. - Male Headwear (Late 12th Century – 14th Century):

– The hood became a characteristic accessory to cover the head.

– In the late 12th century, the hood separated from the garment and was worn as an independent accessory with a short pelerine.

– In the 14th century, a long band called cornette or coquille that hung was added to the tip.

– Towards the end of the 14th century, the gaban emerged, which could incorporate a hood. - Male Headwear (15th Century):

– Evolution of the caperuza: sometimes rolled over the opening of the visagière; the cornette was rolled forming a turban.

– The formed caperuza became a true hat (with a brim).

– The bourrelet (roll) appeared and, around 1460, the cramignolles (headwear with cut edges).

– Throughout the 15th century, felt and beaver hats became popular with multiple shapes (peaks, round or bulging crowns, inverted cones) and various types of brims. - Female Headwear (12th–13th Centuries, Hispanic Kingdoms):

– Social imperative to wear the head covered (capite velata).

– Tocas (simple veils) were common; the word «toca» spread throughout Europe.

– The almízar (a kind of turban with a chin strap), possibly due to Andalusian influence, was used by the nobility.

– Women’s hats did not appear until the second half of the 13th century and were reserved for travel or outdoor activities.

– The crespina (hairnet) was used from the Middle Ages and at the beginning of the Renaissance. - Female Headwear (Second half of the 14th Century – early 16th Century):

– The corniform headpiece (horn-shaped) emerged in the peninsular north; the oldest representations are dated to the northern plateau (Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos, ca. 1384–1388).

– It spread in the 15th and early 16th centuries over a wide area between Galicia and Aragon.

– Burgundian hennins and extreme variants (pointed bell-tower type headwear) appeared around 1440, which could reach up to 1.2 m in some cases.

– In the 15th century, female headwear became complex technical structures: tall, conical, with veils and nets.

- Male Headwear (13th Century):

- Transition Middle Ages → Modern Age (Late 15th – early 16th Century)

-

- Late 15th Century: Existence of the guild of bonnet makers, clearly differentiated from hat makers and toca makers (manufacturers of tocas/veils).

- Turn of the 15th–16th Century (c. 1500): The cap is born: a soft, flexible, rounded and flattened headpiece, with a folded brim; it begins to be imposed in civil attire.

- Early 16th Century (ca. 1500–1525): The bonnet was still used in courtly circles, but began to be replaced by the cap and the hat in civil fashion.

- First quarter of the 16th Century: Corniform headwear continued to be represented in areas such as Ezcaray and Mondoñedo.

- After 1531: The cap and the hat (the latter with a brim) were consolidated as the main male head accessory in the civil sphere, replacing the bonnet; the cap tended to reduce its size.

- Second quarter of the 16th Century onwards: The bonnet remained reserved for specific areas (ecclesiastics, students, bachelors, doctors) and lost its generalized use.

- Fundamental Distinction (summary note)

-

- Cap vs. Hat / Bonnet:

– A cap is a soft garment, without a brim or visor.

– A hat is defined by having a brim around the crown; in the 15th century, hoods already converted into hats appeared and felt and beaver hats with brims became popular.

– The bonnet (capiello) is traditionally a rigid or semi-rigid cap of medieval heritage; over time it was limited to ecclesiastical and academic uses.

- Cap vs. Hat / Bonnet:

The Uncovered Head, a Medieval Disrespect? The Meaning of Headwear

Headwear, or tocado, was an essential element of both male and female attire in the Middle Ages, regardless of social standing. Far from being mere ornaments, headwear functioned as clear indicators of social status, profession, and, in the case of women, even marital status. Its variety of forms and names, especially in the male world, was immense, and every detail told a story. From modest peasant tocas to elaborate noble hennins, each piece on the head dictated a place in the complex medieval hierarchy, turning historical reenactment into an art of precision.

Male Headwear: Between Functionality and Distinction

Medieval men had a wide repertoire of headwear which, in principle, were divided into categories such as bonnets, hats, rolls, and capirotes. Each had a specific purpose and symbolism.

Medieval men had a wide repertoire of headwear which, in principle, were divided into categories such as bonnets, hats, rolls, and capirotes. Each had a specific purpose and symbolism.

The Bonnet and the Capiello: From Military Helmets to the Symbol of Knowledge

The bonnet, known in the Middle Ages as capiello, is a name that dates back to the Roman pileus. Its inspiration comes from the military world, specifically from the cylindrical helmets of the 13th century. Although it was worn by privileged classes and royalty, its legacy endured, being adopted in the 16th century by scholars and “long-robed individuals,” who retained it when fashion had already advanced. Within this category we find:

- The carmeñola: a simple cap tightly fitted to the head, with a rounded crown.

- The galotas and coifs: similar to carmeñolas, but with two extensions that covered the ears, sometimes with ribbons to tie under the chin. They were used to gather hair, provide warmth, or even as sleeping caps.

- Conical or cylindrical shapes: with the point more or less pronounced depending on the period.

The Capirote and the Gugel: Hoods that Ascended and Transformed

The capirote, a medieval heritage headpiece, combined hood and collar in a single garment. Like the bonnet, it was retained by scholars in the 16th century and, surprisingly, was also worn by women for a brief period in the Late Middle Ages. The gugel, popular in Germany from the High Middle Ages, began as a simple hood that covered the shoulders. However, its evolution led it to nobility from the 14th century, with its point significantly lengthening. These models were usually made of wool.

The Male Hat: A Brimmed Piece that Gained Ground

Although brimmed hats were not common among the high nobility, the “beret-type capiello,” with its central tail or “bellows” effect, was worn by clerics, doctors, and military orders. Brimmed hats, made of vegetable materials or wool felt, with a square or hemispherical crown and brims of varying widths, were often held in place with a cord.

Female Headwear: Beauty, Status, and the Imposing Structures of the Late Middle Ages

For women, head covering was a social obligation, which led to an astonishing diversity of headwear, especially from the Late Middle Ages onwards.

The Tocas and Veils: Simple Elegance and the Andalusian Echo

The toca, a Hispanic word that spread throughout Europe, consisted of a rectangular or semi-circular cloth that covered the head and fell over the shoulders. It could be worn loose, fastened with a ribbon on the forehead, or pinned under the chin. Andalusian influence led to the acceptance of translucent and transparent fabrics. The almaizar, a kind of turban with a chin strap, was distinguished in its Christian version by this band that adjusted to the neck.

The Crespinas and Coifs: Gathering Hair with Style

The crespina, a hairnet or coif, was used by women to gather their hair, acting as an adornment. In the Middle Ages, the same name was given to a hairnet made of hair. Men also used them to protect themselves from the cold, and even warriors wore them under metal helmets to prevent chafing. The coif, for its part, was a toca fitted to the hair, often worn under other hats.

The crespina, a hairnet or coif, was used by women to gather their hair, acting as an adornment. In the Middle Ages, the same name was given to a hairnet made of hair. Men also used them to protect themselves from the cold, and even warriors wore them under metal helmets to prevent chafing. The coif, for its part, was a toca fitted to the hair, often worn under other hats.

Corniform and Hennin Headwear: Majesty that Defies the Sky

In the Late Middle Ages, especially in the peninsular north and southwestern France, the imposing corniform headpieces emerged. These structures were formed by several meters of linen or canvas bands rolled over wicker frames, or even parchment and leather, creating what looked like “horns”. A taller headpiece meant greater wealth and status, and it is speculated that its origin might be linked to the Flemish Henin, the “pointed bell-tower type” headpieces that could reach up to one meter and twenty centimeters in height, from which long veils and nets hung.

In the Late Middle Ages, especially in the peninsular north and southwestern France, the imposing corniform headpieces emerged. These structures were formed by several meters of linen or canvas bands rolled over wicker frames, or even parchment and leather, creating what looked like “horns”. A taller headpiece meant greater wealth and status, and it is speculated that its origin might be linked to the Flemish Henin, the “pointed bell-tower type” headpieces that could reach up to one meter and twenty centimeters in height, from which long veils and nets hung.

Materials that Gave Life to Medieval Headwear

The choice of material in a medieval hat was as crucial as its shape, as it directly communicated social status and occasion of use. The guilds of hatmakers, bonnet makers, and toca makers specialized in the art of transforming various elements into pieces that adorned and protected.

From Humble Straw to Sumptuous Silk: A Hierarchy of Fabrics and Felts

Hats and headwear were made from a wide range of materials:

- Wool and Felt: These were the most common materials, especially for working classes and for protection against the cold. Felt allowed for a great variety of shapes and was popular in hat making.

- Leather: Used in hats for knights and people of high status, it offered durability and resistance.

- Straw and Palm: Ideal for summer hats, light and accessible, mainly used by lower classes for sun protection.

- Velvet and Silk: Exclusive to nobility and upper classes, these materials, often combined with embroidery, gold, and silver threads, transformed a simple headpiece into an opulent declaration of wealth.

- Linen and Cotton: Used in veils and coifs, especially in simpler tocas.

The manufacture of felt hats became popular, with specialized guilds improving quality and production, although some processes, such as mercury felting, were dangerous.

Recreating History: Tips for Choosing Your Medieval Headwear

For the historical reenactor, authenticity is paramount. Choosing the right headwear is key to contextualizing your character and era. Here are some recommendations:

- For Nobles: Opt for elaborately decorated hats or headpieces, with materials such as velvet or silk. Bonnets with subtle adornments or coifs under wide-brimmed hats are excellent options for the male noble. For female nobility, corniform headpieces or hennins, though imposing, are faithful representations of Late Middle Ages fashion.

- For Peasant Women: Simple veils, often over coifs or similar caps, are the most authentic choice. These could vary in style depending on the region. The crespina is also an excellent option for modestly gathering hair.

- For Scholars or Clerics: Birretes and rigid bonnets are characteristic of these figures.

- For Warriors: Crespinas were worn under helmets for comfort and protection.

Remember that medieval authors sometimes prioritized symbolism over exact fidelity of clothing in their representations, but the constant is that headwear was a widespread complement throughout society.

Clearing up unknowns about hats in the Middle Ages

What were the most common materials used to make medieval hats?

The most common materials used to make medieval hats were wool, felt, leather, and straw.

The most common materials used to make medieval hats were wool, felt, leather, and straw.

Wool was one of the most popular materials, available in short-pile (smooth or peeled) and long-pile (brushed or frizzy) variants. It provided warmth and was breathable, making it especially useful for protection against the cold.

Felt was also very common, frequently covered with finer fabrics such as taffeta or velvet to give it a more elegant finish.

Leather was used especially in hats for knights and people of higher social status, offering durability and resistance.

Straw was primarily used in summer hats, particularly for the lower classes, being a lighter and more accessible material.

Other less frequent materials included linen, cotton, satin, and materials like palm and rush.

The choice of material largely depended on the social status of the wearer and the availability of resources, as well as the function and season for which the hat was intended.

How did medieval hats vary according to social class?

Medieval hats varied according to social class mainly in materials, quality, colors, and decoration. Nobility and clergy wore elaborate hats made of fine fabrics like silk or velvet, often adorned with gold and silver threads, showcasing splendor and status. The bourgeoisie wore hats of similar styles but with less luxury, imitating the nobility without being able to use exclusive materials. Peasants and lower classes wore simple, functional hats and caps made of common materials like wool, without ostentatious decorations. Furthermore, there were laws that regulated what type of hat and materials could be used according to social class to prevent people of lower status from appearing to have a superior social position.

What hat styles were popular among peasants?

Popular hat styles among peasants were typically braided straw hats or toquilla straw hats, also known as Panama hats or jipijapa, characterized by being lightweight, cool, and functional for outdoor work. These hats have a brim and a medium crown and are handmade from natural fibers such as toquilla straw, very common among peasants and cowboys in the warm regions of America.

In general, peasant hats tend to be made of natural materials and designed to protect from the sun, often with a wide brim for ample shade.

How did medieval fashion influence the creation of hats?

Medieval fashion influenced the creation of hats by turning them into symbols of social status and personal expression, in addition to fulfilling practical functions such as weather protection. The various types of hats and headwear reflected social position: nobles wore elaborate and adorned hats, such as berets, capirotes, or hennins, while peasants and artisans preferred simple, functional wool or felt caps. Over time, these hats diversified in shapes and materials, adapting to more extravagant fashions in the Late Middle Ages and evolving into wide-brimmed hats decorated with feathers for the nobility.

Medieval fashion influenced the creation of hats by turning them into symbols of social status and personal expression, in addition to fulfilling practical functions such as weather protection. The various types of hats and headwear reflected social position: nobles wore elaborate and adorned hats, such as berets, capirotes, or hennins, while peasants and artisans preferred simple, functional wool or felt caps. Over time, these hats diversified in shapes and materials, adapting to more extravagant fashions in the Late Middle Ages and evolving into wide-brimmed hats decorated with feathers for the nobility.

Furthermore, the social obligation, especially for women, to cover their heads prompted the variety and complexity of headwear and hats, from veils to pointed hats related to Gothic fashion. In summary, medieval fashion created a wide range of hats that combined function, class symbols, and fashion trends, laying the groundwork for many of the shapes and styles that persisted in later centuries.

What differences were there between knights’ hats and ladies’ hats?

Differences between knights’ hats and ladies’ hats primarily lay in design, function, and ornamentation. Men’s hats were usually more sober, with practical shapes such as the wide-brimmed hat or the tricorn, and symbols of social status were used, often with moderate decorations like feathers. In contrast, women’s hats were usually more elaborate and ostentatious, with adornments such as ribbons, flowers, feathers, and veils; additionally, they tended to have more varied and striking shapes, such as tall headpieces or wide-brimmed pamela hats, reflecting feminine fashion and social status.

Moreover, regarding etiquette, men had the social obligation to remove their hats in certain situations (churches, greeting, etc.), while women could keep theirs on without such strict rules, which also influenced their use and display.

Men’s hats were more functional and discreet, with symbolisms linked to status and profession, while women’s hats were more decorative, varied in shape, and oriented towards fashion and visual splendor.

In the Middle Ages, headwear was much more than a simple garment: it was a visual code that revealed the identity of each individual. From the humble wool cap to the majestic hennin, each headpiece told a story of status, occupation, and belonging. For you, reenactor or history enthusiast, delving into the world of medieval hats is mastering the art of authenticity, reliving a past where every detail on the head was a declaration of intent. Dare to explore these fascinating accessories and complete your journey to the Middle Ages with the perfect piece.

VIEW MEDIEVAL HATS | VIEW COIFS | VIEW HAIRNETS | VIEW DIADEMS AND TIARAS | VIEW CAPS | VIEW GUGELS | VIEW PARLOTAS | VIEW HEADWEAR | VIEW VEILS AND TURBANS