Legend has it that, in the silence of the workshop, metal whispers tales of battles, rituals, and offerings. Japanese swords are not merely weapons; they are forged testaments to the soul of a culture. In every curve of the blade lives a decision made in the heat of combat, in every polish, ancestral patience is revealed. What makes them unique and why has their aura traveled so far through time and into the collective imagination? Here you will discover the answer: from their straight origins to the katana, through the tamahagane technique, the great legends, and the current role of replicas and martial practices.

Chronology of the Evolution of Japanese Swords

To understand the katana and its relatives, it is essential to look at the timeline: each historical period introduced changes in design, use, and meaning.

| Period | Events |

|---|---|

| Kofun (250-538 AD) |

|

| Asuka (538-710 AD) |

|

| Nara (710-794 AD) |

|

| Heian (794-1185 AD) |

|

| Kamakura (1185-1333 AD) |

|

| Muromachi (1336-1573 AD) |

|

| Sengoku (1467-1573 AD) |

|

| Azuchi-Momoyama (1573-1603 AD) |

|

| Edo (1603-1867 AD) |

|

| Meiji (1868-1912 AD) |

|

| Taishō (1912-1926 AD) |

|

| Shōwa (1926-1989 AD) |

|

| Heisei (1989-2019 AD) |

|

| Reiwa (Since 2019) |

|

Events without specific dates within sword history

|

|

Why Does the Katana Embody Legend?

The katana is the image evoked by the samurai and his code. It has a geometry designed for cutting and for quick unsheathing. But its greatness lies not only in its effectiveness: each katana is the sum of techniques, rituals, and an aesthetic vision. When a blacksmith signs a piece, he leaves more than his name: he leaves a prayer of steel.

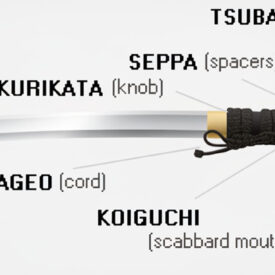

Quick Anatomy and Terms to Know

- Ha: the cutting edge.

- Mune: the back of the blade, unsharpened.

- Hamon: the temper line that appears when tempering the blade and is, at the same time, a technical mark and ornamentation.

- Tsuba: the guard, which can be simple or a work of art in itself.

- Tsuka: the wrapped handle, which ensures a two-handed grip.

Classic Types: The Warrior’s Catalog

Japanese swords respond to needs and combat styles. Each form corresponds to a story. Below, a tour through the most emblematic ones, integrating historical images and replicas that show their physiognomy.

Katana

The Katana is the sword that, when unsheathed, demands respect. Curved blade, long handle, swift unsheathing: it is the tool for close combat and the symbol of the daishō at its finest.

Naginata

The Naginata is a polearm with a curved blade at its end. It was the choice of onna-bugeisha and infantry who sought to maintain distance and sweep formations.

Nodachi / Ōdachi

The Nodachi is the field sword: a huge blade that extends the warrior’s reach and demands singular strength and technique for its handling.

Sai

The Sai retains the flavor of a tool converted into a weapon: an unsharpened dagger with two side prongs for trapping and deflecting. Its silhouette is striking due to its symmetry.

Shirasaya

The Shirasaya is the simple wooden mounting that protects the blade at rest. It is not meant for combat: it is the sheath that preserves the beauty of the blade between battles.

Tachi

Predecessor of the katana, the Tachi was the horsemen’s sword: more curved and longer, designed for cuts from horseback.

Tantō

The Tantō is the hidden dagger: short, lethal in confined spaces, and with a strong ceremonial significance in certain contexts.

Wakizashi

The Wakizashi accompanies the katana in the daishō. Shorter, perfect for defense in confined spaces and for rituals where the presence of a blade must be kept close.

Iaito

The Iaito is the unsharpened sword for iaidō practice: it seeks precision of movement and the practitioner’s responsibility rather than cutting.

Bokken

The Bokken is the wooden sword of the dojo: it replaces the real blade for training and learning distance, rhythm, and respect for technique.

Nagamaki

The Nagamaki is the exotic suggestion: similar to a naginata or a tachi with an extra long handle, it was popular between the 12th and 14th centuries and is now reserved for collectors and schools that preserve forgotten techniques.

The Art of Forging: Tamahagane, Double Steel, and the Hamon

The forging of a traditional Japanese sword is not an industrial technique: it is a metallurgical ritual. Tamahagane, a steel obtained from iron sand and charcoal, is the base. The blacksmith separates, classifies, folds, and combines pieces of different carbon to achieve harmony between a hard edge and a flexible core.

Essential Steps in Creating a Blade

- Obtaining tamahagane: melting in the tatara. Hours of control to obtain the correct steel.

- Classification and folding: the steel is heated and repeatedly folded to eliminate impurities and homogenize the carbon.

- Compound forging: outer layers of hard steel and a more ductile core to prevent brittleness.

- Clay and tempering: applying clay to the spine and edge creates the hamon when tempering the blade in water, producing the temper line that distinguishes each school and each master.

- Curvature and polishing: immersion and thermal change create the curve; polishing, performed with specific stones, reveals the soul of the blade and can take weeks.

The Hamon: Technique and Beauty

The hamon is not just an ornament: it is the imprint of differential tempering. Its design (notare, suguha, choji, etc.) speaks of the forger’s school and the character of the blade. From a distance, a katana is recognized by its silhouette; up close, by the story its hamon tells.

Technique and Combat: Why Curves Matter

The curvature of the Japanese sword is not an aesthetic accident: it responds to the dynamic of use. In mounted combat and quick foot engagements, a curved blade facilitates cutting and unsheathing. Additionally, the presence of the mune allows for receiving and deflecting blows without sacrificing the edge.

The Five Swords Under Heaven and Other Legends

In Japan, swords become myths. The Tenka Goken bring together pieces that were considered unsurpassed in beauty and power: Dojikiri Yasutsuna, Onimaru Kunitsuna, Mikazuki Munechika, Odenta Mitsuyo, and Juzumaru Tsunetsugu. Each one brings with it tales of gods, monks, and warriors.

Myths that are part of the imaginary

- Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi: the legendary weapon of Susanoo, part of the Three Sacred Treasures of Japan.

- Honjo Masamune: the katana of master Masamune which, lost in time, acquired the status of an almost untouchable symbol.

Mountings, Fittings, and Blade Care

A nihontō does not end with polishing: the tsuba, habaki, saya, and tsuka share the visual narrative of the blade. A simple mounting, like the shirasaya, preserves the blade; a luxurious mounting turns it into a ritual object. Care requires cleaning with oil and special cloths to prevent corrosion.

Replicas, Practice, and Collecting

Today, traditional swords, functional replicas, and practice models coexist. Each serves a different purpose: cultural preservation, martial training, or exhibition. Understanding their purpose prevents errors in conservation and use.

How to differentiate replicas and traditional blades

- Blades forged in tamahagane and worked by certified blacksmiths maintain ancestral techniques and usually have a signed nakago.

- Replicas can be made of modern steel; some are functional, others decorative; the finish and mounting help identify them.

- The iaito is made without an edge for safe iaidō practice; the bokken is made of wood for training.

The Sword in Contemporary Culture

From cinema to comics and anime, the katana and its sisters have traveled the world. It is no coincidence: their aesthetics and symbolic weight connect with universal archetypes: honor, sacrifice, and mastery. The revival of traditional martial arts has also boosted interest in learning techniques like iaidō and preserving nihontō craftsmanship.

Comparative Tables: Sizes and Uses

| Type | Approximate blade length | Historical use | Distinctive feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chokutō | 30–90 cm | Ceremonial and early combat | Straight blade, single edge |

| Tachi | 70–80 cm | Cavalry | More curved, worn with edge down |

| Katana | 60–70 cm | Close combat, samurai symbol | Moderate curve, quick unsheathing |

| Wakizashi | 30–60 cm | Secondary weapon, defense in confined spaces | Companion to the katana (daishō) |

| Nodachi/Ōdachi | 90–120+ cm | Battlefield, reach | Large size, two-handed use |

Questions every sword lover should ask themselves

Before approaching a katana or a replica, ask yourself: are you looking for history, practice, or aesthetics? Each answer changes the appropriate piece and its maintenance. The collector’s responsibility is as great as the practitioner’s: respect for the work and its context.

Remember that a Japanese sword is a dialogue between metal, fire, and knowing hands. Behind each piece is a workshop, a school, and a story that deserves to be read carefully. Maintain curiosity; let the word hamon take you to the moment when water met steel and the curve you now recognize as a katana was born.

E

E