What does the Alfonso X The Wise sword represent today? More than a weapon, the sword attributed to Alfonso X is a visual symbol of a reign that combined military power, political ambition, and an intense passion for letters and sciences. In this article, we will explore the historical context of the monarch, the design and technical details of the sword associated with his figure, how modern replicas are made, and what a collector or enthusiast looking for a faithful and durable piece should value. You will learn to identify historical features, common materials in reproductions, and how to maintain a replica to preserve its presence and value over time.

The figure of the king and the sword as an emblem

Alfonso X, known as “The Wise,” was a complex figure: king, promoter of knowledge, legislator, and strategist. Born in Toledo in 1221, his reign (from 1252) was characterized by administrative advances, cultural promotion, and scientific projects such as the Alfonsine Tables. In parallel, his image as a monarch materialized in symbolic objects, among them the royal sword, which in the medieval mentality condensed attributes such as justice, moderation, and strength, collected in legal texts such as the Siete Partidas.

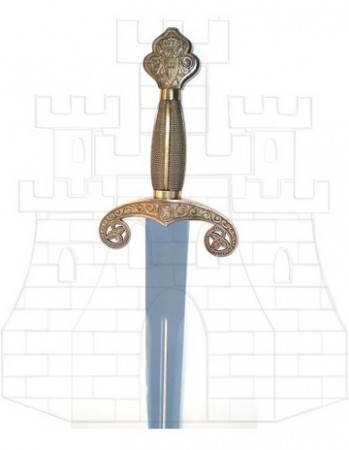

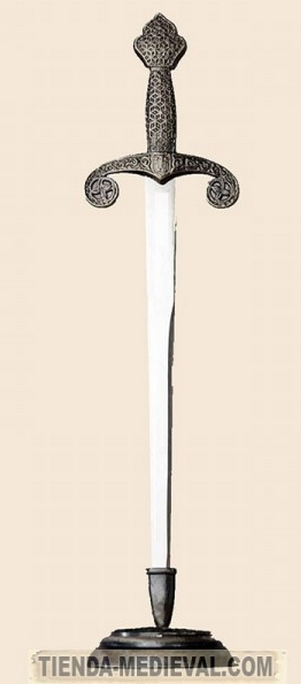

When we refer to the Alfonso X The Wise sword today, we normally mean historical replicas inspired by 13th-century forms and decorations: cross guard, decorated pommel, almond-shaped hilt, and long blades with a central fuller and engravings. These replicas function as study pieces, decoration, and historical reenactment, connecting the observer with the imaginary of the Alfonsine reign.

Essential Chronology of Alfonso X the Wise

Summary chronology of the main milestones of his life, government, and intellectual work.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1221 | Birth of Alfonso X, son of Ferdinand III and Beatrice of Swabia. |

| 1231 | At the age of ten, he participates in a raid against the Moors. |

| 1235 | His mother, Beatrice of Swabia, dies. |

| 1240 | Ferdinand III assigns him his own household. |

| 1242 | Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada describes the repopulation of Córdoba and the attractiveness of the conquered lands. |

| 1243 | As an infante, he presides over a Castilian embassy to the Murcian lands; the pact of Alcaraz is signed, incorporating the Taifa kingdom of Murcia into the Crown of Castile (controversy in Cartagena, Lorca, and Mula); the text of the Lapidary, which Alfonso commissioned to be translated into Castilian, is rescued; Judah ben Moses ha-Cohen is already linked to Alfonso as a collaborator. |

| 1245 | The localities of Cartagena, Lorca, and Mula definitively surrender to the Christians after Alfonso’s military intervention. |

| 1249 | He marries Violante of Aragon in Valladolid. |

| 1250 | The translation of the Lapidary into Castilian is completed. |

| 1252 (May 30) | Ferdinand III dies; Alfonso ascends to the throne of Castile and León; he commissions the creation of the Fuero Real to unify the laws; he possibly receives a dedication from Peter of Provence. |

| 1254 | Founding of several professorships at the University of Salamanca. |

| 1255 | The town of Villa Real in La Mancha is founded; Millán Pérez de Ayllón copies the original of the Fuero Real. |

| 1256 | An embassy from Pisa arrives proposing Alfonso as an imperial candidate; he is presented as King of the Romans and elected emperor; Richard of Cornwall is also elected, initiating a dispute; Alfonso makes a donation to Bernardo de Brihuega in Seville. |

| 1257 (April 1) | Alfonso X is elected emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, without managing to consolidate his position. |

| 1260 | He initiates an expedition to North Africa, temporarily conquering the city of Salé; he resides in Seville (until 1268). |

| 1262 | He takes the port city of Cádiz; he orders astronomical observations in Toledo and the construction of instruments (until 1272), considered the first observatory in the Christian West. |

| 1263–1272 | Ishaq ben Sid and Yehudé ben Mosé conduct astronomical observations in Toledo that will lead to the Alfonsine Astronomical Tables. |

| 1264 | Strong Mudejar uprising in Betica Andalusia and the Kingdom of Murcia; after suppressing it, the expulsion of Mudejars from Betica Andalusia is decreed (especially Jerez); James I of Aragon pacifies Murcia. |

| 1266–1267 | Notable land distribution in the city of Murcia, similar to that of Seville. |

| 1268 | Isaac ben Sid copies an Arabic manuscript on automatons. |

| c. 1270 | The writing of the great historiographical works begins: the Primera Crónica General de España and the Grande e General Estoria. |

| 1270–1271 | Application of a depreciation in the bullion policy (negative result); the obtaining of borrowed books from the monasteries of Nájera and Albelda for historical and legal purposes is documented. |

| 1271 | Meeting in Lerma preceding the noble revolt. |

| 1272 | Revolt of the high nobility (Lara, Haro, Castro, Saldaña lineages) due to the generalization of the Fuero Real and fiscal policy; Richard of Cornwall, Alfonso’s imperial rival, dies. |

| 1273 | Rudolf of Habsburg accedes to the Germanic imperial title, marking the definitive failure of Alfonso’s imperial aspiration; the Honrado Concejo de la Mesta is instituted to control livestock activity. |

| 1274 | Queen Violante intervenes and manages to appease the noble revolt. |

| 1275 | Pope Gregory IX forces Alfonso X to renounce his imperial aspirations; Ferdinand de la Cerda, firstborn and heir, dies, causing a succession conflict. |

| 1276 | A master Roldán composes the Ordenamiento de las tafurerías by order of the king. |

| 1278 | Juan Gil de Zamora composes the Historia naturalis and De preconiis Hispanie. |

| c. 1280–1290 | Álvaro de Oviedo works for the Archbishop of Toledo, Gonzalo Pérez Gudiel. |

| 1282 | Sancho (future Sancho IV) convenes Cortes in Valladolid claiming the throne against the rights of the Cerda heirs; a civil war begins that confines Alfonso to Seville; Alfonso resumes the Estoria de España in Seville from a primitive draft. |

| 1284 | Alfonso X dies in Seville; before that, he expresses his will to forgive Sancho and those who offended him; his remains are deposited in Santa María de Seville alongside those of his parents. |

Why it interests historians and collectors

The sword linked to Alfonso X attracts attention for several reasons:

- Historical context: it represents the transition to a centralized kingdom and the projection of Castile in the Peninsula.

- Legal and cultural symbolism: the sword embodies the idea of the monarch as a legislator and protector of order.

- Medieval aesthetics: the design, with its ornamented cross and pommel, connects with the goldsmithing and heraldry of its time.

- Faithful replicas: modern manufacturers offer reproductions with exhaustive details, useful for research, private display, or historical reenactment.

Brief guide to understanding a historical replica

When evaluating a replica of the Alfonso X The Wise sword, it is advisable to consider several technical and aesthetic aspects:

- Blade material: tempered steel (e.g., 1060) in high-quality replicas; stainless steel in decorative models.

- Length: reproductions come in various sizes: 56 cm and 76 cm for short or display versions, and 103 cm for the natural length of a hand-and-a-half or long sword from the 13th century.

- Guard: guard with arched arms, trefoil or Gothic motifs at the ends, often silver-plated or gilded.

- Finishes: engravings on the blade, carved pommels, almond-shaped hilts or with ornamental mesh that reproduce medieval aesthetics.

Design and characteristic elements of the sword attributed to Alfonso X

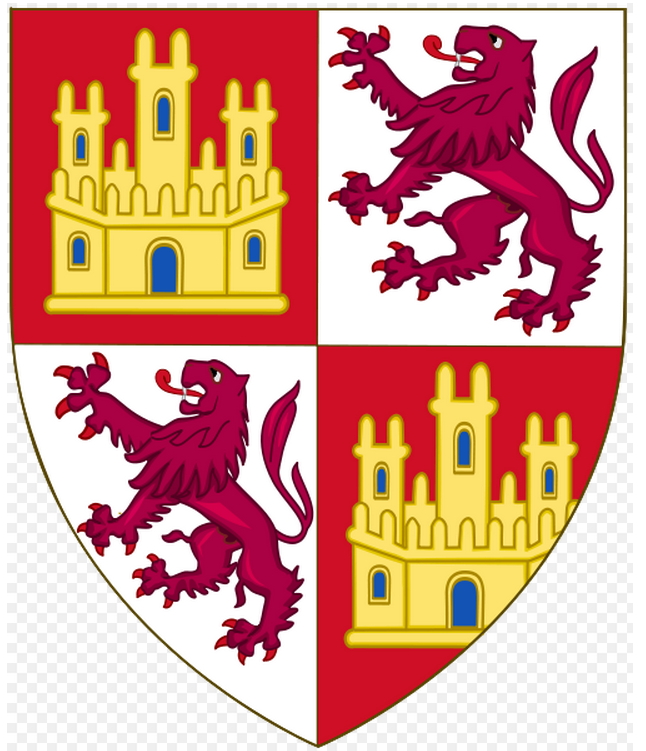

The preserved descriptions and modern replicas coincide in several features: double-edged blade, very marked central fuller (or canalillo) that attenuates in the final third, trimmed point, and cross with curved quillons. The ornamentation includes heraldic motifs (arms of Castile and León on the cross), and pommels with atauriques and floral motifs typical of Gothic goldsmithery transitioning to late Romanesque.

Symbolic interpretation in the Siete Partidas

In the legal work attributed to his court, the Siete Partidas gather ideas about royalty, justice, and the virtues that the monarch should embody. The sword as a symbol is a graphic element that reinforces the image of the wise king: moderation, strength, and prudence. That is why contemporary replicas incorporate details that highlight this balance between authority and wisdom.

Most common materials and dimensions in replicas

High-end replicas use quality steels and tempering techniques that provide resistance and flexibility. Among the common measurements:

- Blade: between 80 and 90 cm in long replicas, 70–76 cm in hand-and-a-half versions; some technical sheets indicate 103 cm for life-size copies of the collection model.

- Weight: replicas around 1,200–1,600 grams for balanced handling; heavier and less balanced decorative models can exceed 1.5 kilograms.

- Thickness: blades with 3–4 mm thickness in the middle zone to ensure integrity and usability in historical reenactment.

Aesthetic finishes: gilded, silver-plated, and patinas

Depending on the purpose (decoration, collecting, or use in reenactment), finishes vary. Gold plating and silver plating highlight the regal and commemorative status of the piece. Patinas and rustic finishes offer a more “historical” appearance, while chiseled details on the pommel or cross reproduce Gothic and Mudejar models typical of Alfonso X’s court.

Commemorative editions and collection pieces

On the occasion of historical anniversaries, limited editions have appeared that replicate the aesthetics of the royal sword. Descriptions of these series mention an over-gilded guard, hilts with Gothic-style mesh, and carved floral pommels. They often feature heraldic engravings and present the blade with engraved decoration in geometric and heraldic motifs.

How to evaluate the historical accuracy of a replica

To determine the fidelity of a replica, it is advisable to check:

- Technical documentation: a sheet with materials and manufacturing processes.

- Goldsmithing details: correct engravings on the blade, proportions of the cross, and pommel shape consistent with 13th-century archetypes.

- Balance: good weight distribution between blade and pommel; a well-reproduced historical sword allows for realistic handling.

- Finishes: verifiable artisanal work in plating and chiseling.

Care and conservation of a historical replica

Even replicas with stainless steel require visual and structural maintenance. Basic recommendations:

- Clean the blade with a soft cloth after handling and apply a light layer of protective oil if it is carbon steel.

- Avoid humid environments or prolonged contact with water that promotes corrosion.

- Store the sword in breathable sheaths or displays with separation from acidic materials.

- Check rivets and fixings of the guard and hilt to prevent looseness in recreational use.

Most common uses of replicas

Replicas of the Alfonso X sword serve various functions:

- Decoration and historical ambiance in interiors.

- Material for theatrical and cinematographic representation.

- Collection piece for enthusiasts of the Middle Ages and Spanish history.

- Educational tool that allows appreciation of proportions, techniques, and symbolisms of medieval weaponry.

How to choose the right replica according to its use

If the purpose is decorative, the finish and ornamentation should be prioritized. For use in historical reenactment or handling, the steel composition, tempering, and balance are paramount. Some recommendations:

- Decoration: evaluate plating, patinas, and the quality of ornamental work.

- Reenactment: choose tempered steel, solid rivets, and measurements that allow for proper handling technique.

- Collection: opt for limited editions or pieces with documentation certifying the artisanal process.

Verify authenticity and technical quality

Although it is a replica, authenticity in terms of historical fidelity and technical quality is ensured through manufacturer documentation, specialist reviews, and inspection of details: steel marking, workshop bending tests, chroming or precious metal plating, and the quality of the engraving on the blade.

The material and symbolic legacy of Alfonso X

Alfonso X left a mark that transcended the military: he promoted Castilian prose, fostered translations, and created legal and astronomical corpora that shaped Iberian administration and culture. The sword, as an emblem of that reign, recalls the monarch’s dual role: strategist and patron of knowledge. That is why the reproduction of his weapon brings us closer not only to a piece of metal but to a time of cultural exchange between Latins, Hebrews, and Muslims at the Toledo School of Translators.

SEE ALFONSO X THE WISE SWORDS | SEE OTHER HISTORICAL SPANISH SWORDS | SEE ALL TYPES OF SWORDS

The Alfonso X The Wise sword continues to be a gateway to understanding the complexity of the 13th century in the Peninsula: its mixture of power and knowledge, legal norms, and intellectual creativity. A well-made replica allows us to hold that bridge between history and contemporary sensibility and to remember that objects — like the sword — are vectors of cultural memory.