What does it feel like when a blade cuts through the air in a perfect arc, when a spin becomes poetry, and the weight of the sword seems to become an extension of your own body? Kung Fu swords are not just combat tools: they are instruments of discipline, aesthetics, and cultural memory. In this article, you will discover the history, technique, proper selection according to your goal (practice, competition, or collection), essential blade care, and how to integrate sword training into your martial journey.

From Jian to Wushu: Historical Journey of Chinese Swords and Kung Fu

The history of Chinese swords and Kung Fu spans millennia. Understanding this journey gives you context to choose the right sword and respect the tradition of its use. The following chronology synthesizes the most relevant stages and will help you place the Jian and Dao in their own time.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| Antiquity (over 2500 years) — Spring and Autumn Period | |

| Jian Design | The design of the Jian sword dates back over 2500 years; the first bronze versions appeared and were used during the Spring and Autumn Period. |

| Cultural and Martial Role | For many centuries, Chinese swords have captivated warriors, collectors, and martial artists; Chinese martial arts possess a rich and long history. |

| Civilizational Symbol | In early times, when tools and weapons were less differentiated, the appearance of the sword marked the beginnings of armed civilization and military techniques. |

| Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) | |

| Use in Battle | The sword was not a primary weapon in Han Dynasty battles; the saber (dao) and spear were the predominant weapons. |

| Song Dynasty | |

| Origin of Weapons | The origin of hook swords is attributed to this dynasty, according to various traditional sources. |

| Ming Dynasty | |

| Dao Popularity | The dao (saber) became especially popular among soldiers during the Ming Dynasty. |

| New Forms and Techniques | The origin of weapons such as the Cicada Wing Blade and the Wind and Fire Wheel is mentioned during this era. |

| Criticism of the Sword | In Wu Shu’s text “Arm Record” (手臂錄), late in the Ming Dynasty (1611–1695 AD), sword practitioners were already harshly criticized, stating that the technique had “extinguished.” |

| Qing Dynasty (18th–19th centuries) | |

| Persistence of the Dao | The dao remained a popular weapon among soldiers; however, many weapons associated with Kung Fu began or spread in the 18th–19th centuries. |

| Real Origin of Many Weapons | Some sources suggest that many weapons attributed to the Ming Dynasty actually originated in the 18th–19th centuries, in an era marked by an increase in banditry and non-military weapons. |

| Short Swords | Short swords of the Qing Dynasty were used as status symbols or for personal defense; no fighting systems with them have survived. |

| Mid-20th Century | |

| Modernization of Martial Art | Wushu is established as a modern sport in China, with the purpose of standardizing traditional practices for competition and exhibition. |

| 21st Century (Present) | |

| Contemporary Practice | Chinese swords remain essential in contemporary martial arts; the Jian and Dao are used in styles such as Wushu and Tai Chi. |

| Cultural Presence | Sword culture remains alive in dance, theater, commercial design, painting, sculpture, collectibles, souvenirs, and video games. |

| Modern Need | There is a demand for a contemporary sword that combines martial functionality, modern aesthetics, and affordability for 21st-century practitioners. |

| Kung Fu Concept | The term “Kung Fu” transcends martial arts: it denotes any skill acquired through hard work and dedication. |

| Teaching and Evolution | The Shaolin Temple teaches both traditional Kung Fu and modern Wushu; Wushu is interpreted as a modern evolution focused on flexibility, power, and fluidity, with Olympic potential. |

Why the Sword Matters in Your Martial Practice

Training with a sword develops qualities that empty-hand work does not fully offer: synchronicity between shoulder, wrist, and hip; sensitivity at the tip; control of rhythm and space; and an aesthetic that reinforces internal discipline. Sword forms also preserve ancient technical principles and transmit martial philosophy: economy of movement, respect, and precision.

Essential Types: Jian and Dao

In practical terms, when talking about Kung Fu swords, you will almost always find two sides of the same coin: the Jian (double-edged, straight) and the Dao (single-edged, curved or slightly curved). Each demands a distinct technique, rhythm, and sensibility.

| Type | Profile | Predominant Technique | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jian | Straight, double-edged sword, light and balanced | Precision, thrust, redirection, and fine timing | Wudang, Tai Chi, technical demonstrations, and fine training |

| Dao | Single-edged saber, curved or slightly curved | Broad cuts, circular strikes, and power generators | Wushu, Southern styles, impact techniques, and competition |

- Jian

-

- Use: Elegant forms, control, and thrusts.

- Meaning: Traditionally associated with nobility and art.

- Recommended for: Practitioners seeking precision and technical work.

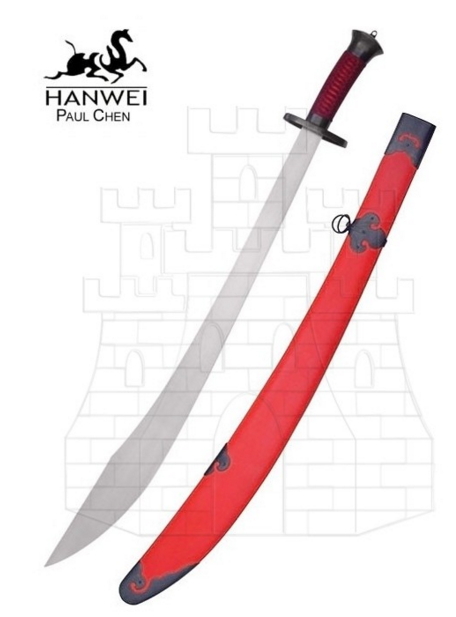

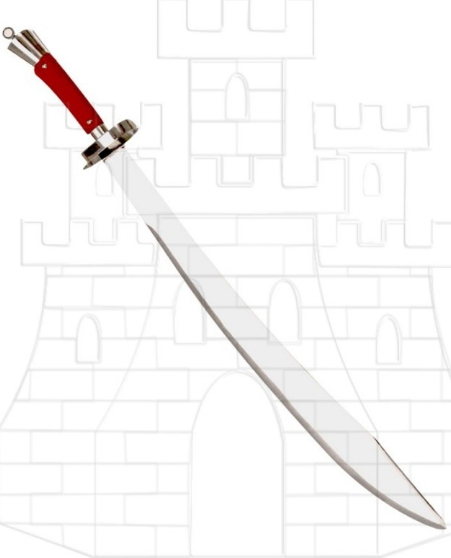

- Dao

-

- Use: Rotary cuts and expansive energy.

- Meaning: Soldier’s weapon, powerful and effective.

- Recommended for: Those who prefer dynamic work, impact, and shows.

Quick Anatomy of a Kung Fu Sword

- Blade: Profile and thickness define flexibility (Wushu) or rigidity (traditional).

- Guard (tsuba/garda): Protects the hand and aids balance.

- Handle: Must allow for a secure grip and fluid wrist movements.

- Scabbard: To protect the blade and facilitate transitions in forms.

Swords for Practice: Models and Recommendations

Depending on your objective (learning, competition, or collection), the material and configuration of the sword change. The following brief guide will help you decide before trying a blade in hand.

Materials and Their Advantages

- High-carbon steel: Excellent for functional replicas; sharpenable and impact-resistant when properly treated.

- Stainless steel: Visually attractive and low maintenance, but less recommended for intensive use.

- Spring steel: Widely used in Wushu for its flexibility and characteristic sound in fast turns.

- Wood / Polypropylene: Ideal for beginners and safe contact practice.

How to Choose According to Your Purpose

If you are going to train: prioritize balance, weight, and a comfortable grip point. For competing in Wushu, look for flexibility and lightness; for traditional forms, a blade with more body and a defined center of gravity. For collecting, value craftsmanship, materials, and historical fidelity.

Quick Guide for Beginners

- Start with a practice sword (wood or polypropylene) to learn trajectories without risk.

- Test the length: when held vertically, the tip should reach approximately the middle of the ear for Tai Chi Jians.

- Check the balance: hold the grip and observe if the blade responds to small movements.

Technique, Tradition, and Etiquette

Practice with a sword is not just technique: it is ceremonial. Salutation, posture, and respect are part of the lesson. Below, I will explain patterns of conduct and exercises that will help you progress safely.

The Salute and Its Meaning

The salute in Kung Fu is an expression of respect and is part of the rules of courtesy in the school. The most common gesture consists of the open left hand over the right fist. If you are carrying a weapon, the hand holding the weapon (dominant) holds it firmly while the palm of the other hand covers the fist. You should salute standing, with your feet together, an upright posture, and looking towards whom you salute; the arms extend to chest height forming a circle.

Initial Exercises to Develop Sensitivity

- Basic Paths: Practice slow, controlled movements with the tip describing a semicircle in front of you.

- Wrist Turns: Without moving the shoulder, work gentle turns to understand the blade’s inertia.

- Posture Transitions: Combine steps (translations) with changes in grip and blade direction.

Wushu vs. Tradition: Practical Differences

Modern Wushu and traditional practice share roots but diverge in objectives. Wushu prioritizes spectacle: thin, flexible blades and broad movements. Tradition seeks martial effectiveness and often uses more rigid and heavier swords. Knowing the difference will allow you to choose a blade according to your goals.

Safety and Maintenance: Protocols that Preserve the Blade and the Practitioner

A well-cared for sword lasts decades; a poorly maintained one rusts or loses shape. Furthermore, correct safety prevents accidents in the dojo.

Daily Maintenance and Storage

- Cleaning: After each use, wipe the blade with a dry cloth to remove sweat and particles.

- Oiling: Apply a light layer of specialized oil (or an appropriate anti-corrosion product) to prevent oxidation.

- Storage: Store the sword in its scabbard and in a horizontal or hung position, avoiding leaving it standing where the scabbard or blade could deform.

Prevention and Safety in Training

- Use protection and unsharpened swords for partner drills.

- Maintain distance and blade control: practice of tip control is as important as strike technique.

- Regularly check bindings, guard, and rivets to prevent unexpected breakages.

Practical Comparison: Choosing a Sword Based on Objective

| Objective | Suggested Material | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Training | Wood or polypropylene | Safety, impact resistance, dull edge |

| Wushu / Competition | Spring steel / flexible steel | Lightness, flexibility, and sound in turns |

| Advanced Practice | High-carbon steel | Balance, resistance, and sharpenable |

| Collection / Exhibition | Forged steel / historical decoration | Artistic finishes, historical fidelity, and details |

The Sword as a Bridge Between Technique and Philosophy

Training with a sword means learning to move with intention. The discipline required to control a blade translates into self-control, patience, and a way of relating to violence based on ethics: defending, not aggressing. Shaolin monks, for example, integrated weapons into their practice without losing the principles of non-violence, understanding that martial art can be a tool for protection and personal balance.

Practical Example of a Short Routine for Integration

- Warm-up (8 minutes): joint mobility and wrist work with a practice sword.

- Fundamentals (10 minutes): basic cuts, thrusts, and tip control in slow movements.

- Transition (7 minutes): steps and posture changes combined with 5 repetitions of each technique.

- Short Form (5–7 minutes): chain 8–10 symbolic movements at a controlled pace.

Final Choice and Recommendations for Progress

Choose the sword that meets your purpose and don’t just be swayed by aesthetics. Test it in hand, evaluate balance, weight, and length. Respect tradition, but adapt the practice to your current needs: safety, maintenance, and adaptation to your training style.

When you hold a Kung Fu sword, you hold centuries of technique and culture. That blade can teach you precision, patience, and a sense of space. It is a learning companion that demands respect and returns discipline.