Legend has it that, before iron spoke in the heat of battle, artisans were already seeking the perfect form for a blade to cut and a handle to obey the warrior’s arm. Understanding the parts of the sword is to trace that history and to know why each piece exists: for balance, for protection, or for design.

In this article, you will discover, with clear language and an evocative gaze, the complete anatomy of a sword: from the sharpest point to the pommel that counterbalances fate. You will learn how the pieces are named, what their function is in combat, how they have evolved over time, and what details distinguish a faithful replica from a decorative blade.

Ready to hold the sword in imagination and unravel its secrets?

The evolution of sword parts through the centuries

- Bronze Age (c. 3000–1200 BCE): The first blades are short and piercing; the concept of a separate hilt and scabbard emerges with the need to protect the blade and the wearer.

- Iron Age and Classical Antiquity (c. 1200 BCE–500 CE): Forging is perfected; swords with a better length/weight ratio and simple early guards appear.

- Early Middle Ages (500–1000): One-handed swords with simple quillons; the tang and pommel begin to integrate into a sturdy whole.

- High Middle Ages (1000–1400): Shift towards longer and heavier blades; the guard evolves to better protect the hand.

- Renaissance and Advent of the Rapier (15th–17th centuries): Complex handguards, rings, and baskets protect the hand; the sword specializes in thrusting and cutting according to technique.

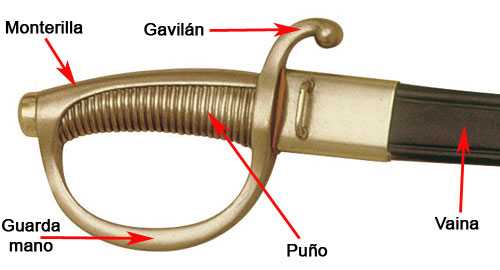

- Modern Era (18th–19th centuries): Sabers and military swords with light pommels and simplified guards; ergonomics seek speed and ease of use.

- 20th Century to today: Historical replicas, fantasy replicas, and collector’s items combine aesthetics and historical research of materials and form.

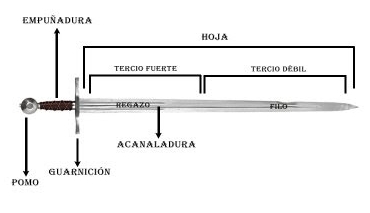

The blade: the cutting and thrusting soul

The blade is the most visible part and the sword’s raison d’être: it cuts, slashes, and thrusts. But within that extension are sections and details, each with a name and purpose.

Internal parts of the blade

- Flat: The visible body of the blade, its length and profile determine how it cuts and how it behaves in the air.

- Edge: The sharp border; it can be single or double. A distinction is made between the forte (near the hilt) and the foible (towards the tip), each with tactical advantages.

- Point: Designed for penetration; its shape (sharp, pointed, blunt) marks the specialization between cutting and thrusting.

- Ricasso or unsharpened tang: Unsharpened section near the guard that allows the sword to be gripped further forward on long blades for greater control.

- Fuller (groove): Longitudinal groove that reduces weight without sacrificing rigidity. It is not a “blood groove,” but engineering to improve handling and reduce inertia.

- Spine or rib: Longitudinal elevation that increases rigidity and defines the cross-section of the blade.

How the blade influences combat

The profile and length of the blade determine the strategy: wide, short blades for slashing, long, sharp blades for reach and powerful cuts, sharp blades for thrusting. Weight and distribution (center of gravity) influence speed and fatigue.

The hilt: control, feel, and balance

The Hilt is the connection between the wielder’s will and the blade. A good design here defines comfort, control, and security.

Tang

The tang is the extension of the blade that extends into the handle. Its form (full, partial, screwed) determines the structural strength. A full tang provides robustness for strong blows; a partial tang reduces weight but requires attention to assembly.

Pommel

The pommel closes the handle and acts as a counterweight that regulates balance. It can be solid and heavy to compensate for long blades or light for agile sabers. Beyond its technical function, the pommel is also an object of ornamentation and symbolism.

Grip

The grip or handle is the surface you hold. Traditionally wood covered with leather, wire, or fibers; today it can include composite materials. Its shape favors ergonomics: round, oval, or with an anatomical section according to tradition.

Monterilla

Characteristic of sabers and some swords, the monterilla is a disc or ring under the pommel that provides balance and prevents the hand from slipping.

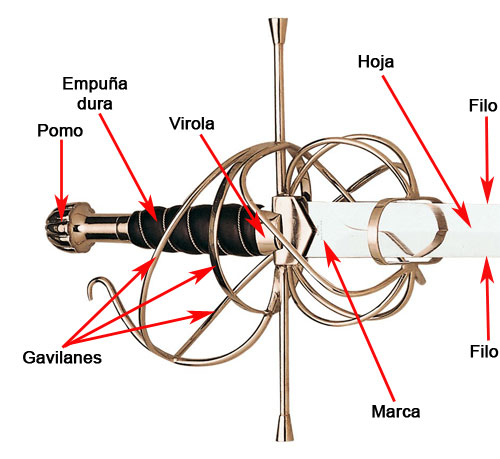

Ferrule

The ferrule is a ring between the guard and the hilt that reinforces the blade-handle union and can be decorative. Sometimes it acts as a stop for the grip’s covering.

Guard and protections: defending the hand

The guard —also called quillon, cross, or arriaz— separates the hand from the blade and prevents injuries. Its evolution is a story of how hand protection was perfected against new combat techniques.

Types of guards

- Simple crossguard: Straight bar typical of early medieval swords.

- Handguard with rings: Designed to protect without sacrificing mobility; typical of rapiers and smallswords.

- Basket hilt or basket guard: Provides total hand protection for heavy fencing.

- Quillons: Curved projections that protect and, sometimes, allow offensive actions with the guard itself.

Quillons: detail and use

The quillons are curved parts of the handguard that wrap around the hand and help redirect blows. In expert hands, they can be used to trap or deflect the rival’s weapon.

Minor but decisive parts

- Shoulder: Area connecting the blade to the base of the guard; its robustness prevents stress fractures.

- Chape (of the scabbard): Metal piece that protects the tip of the scabbard and prevents wear.

- Scabbard mouth: Reinforcement at the upper opening that facilitates drawing and protects the edge.

The scabbard or sheath: protection and presentation

The scabbard protects the blade from the environment and transport. It can be made of wood lined with leather, metal, or modern materials. Its parts —chape, mouth, and straps— are both functional and aesthetic, and historically have served to display status.

Materials and forging: how they influence each part

The choice of metal and the forging technique condition each section of the sword. Carbon steels offer easy tempering; stainless steels resist corrosion; laminated or Damascus steels balance hardness and flexibility.

An excellent edge requires properly treated steel and a tang dimensioned to withstand loads. The guard and pommel are usually made of steel, brass, or bronze, depending on the period and aesthetics.

Balance, geometry, and ergonomics

When you hold a sword, you feel its balance: the point of equilibrium (or center of gravity) defines maneuverability and the sensation in combat. A sword with its center of gravity near the guard responds better in thrusts; another more forward offers powerful cuts.

How the parts are used in combat

- Blocking and parries: The guard and the proximal part of the blade (the forte) are used to absorb and redirect the blow.

- Cutting: The middle and distal section of the blade uses mass and edge to cut soft materials.

- Thrusting: The point and blade geometry penetrate armor or fabric.

- Hilt maneuvers: Grip adjustments on the tang or ricasso allow fine control in prolonged combat.

Assembly and maintenance (basic principles)

Maintaining the integrity of each part ensures the longevity of the sword. Cleaning, moisture protection, and periodic checking of the tang and pommel adjustment are essential tasks. A well-sharpened edge and a scabbard that does not dull the steel preserve both effectiveness and aesthetics.

Types of swords and the presence of their parts

Not all sword parts appear on all weapons. History shows variations based on function:

- Short swords and gladius: Simple pommel and guard, robust blade for short cuts.

- Long swords and bastard swords: Ricasso and longer grip for two-handed grip.

- Sabers: Usually have light pommels and angled guards for cavalry.

- Rapiers and smallswords: Complex handguards and fine point for thrusting.

Historical replicas and collector’s items

Replicas attempt to capture not only the form but also the logic of the original sword parts. A faithful replica reproduces blade dimensions, balance, and guard details; aesthetic variations seek fidelity to the era.

When contemplating a replica, note how the tang is assembled, what materials the artisan has chosen for the hilt, and whether the scabbard respects historical functionality. These details convey the character of the piece.

Essential terminology for enthusiasts and collectors

- Full tang: A tang that runs the entire length of the hilt and reaches the pommel.

- Ricasso: Unsharpened area behind the guard.

- Fuller: Groove to reduce weight.

- Pommel: Counterweight and end of the handle.

- Guard or crossguard: Protection between hand and blade.

What to remember about sword parts

Each piece—blade, guard, hilt, pommel, and scabbard—serves a function that goes beyond aesthetics. Their combination determines the weapon’s behavior, its history, and its use. Knowing these parts allows you to read a sword as you would a map: understanding its intent, its balance, and its legacy.