Charlemagne (Charles I) was much more than a conqueror and legislator: his figure merged with medieval epic, and with it, so did the weapons that accompanied him in the collective memory. In this article we will explore in depth the most famous Charlemagne swords —Joyosa and Durandarte—, their role in literature, their presence in museums and how history and legend intertwine around these objects.

Charlemagne ruled from the late 8th century and throughout the 9th century, and his reign was decisive in shaping medieval Europe. However, when we talk about his swords, we enter a hybrid terrain: a mixture of documented facts, hagiographic accounts, and chansons de geste that transmitted values, symbols, and legitimacy. A named sword was, in the Middle Ages, a symbol of authority, military identity, and religious beliefs.

Why Swords Became Legendary

During the High Middle Ages, a sword was not a mere military tool: it was the extension of the warrior’s honor. From the 8th century onwards, the Christianization of weapons and relics added a sacred layer to many objects. Naming a sword and attributing properties to it —protection against poisons, changeable brilliance, embedded relics— served to connect a ruler with the divine and to give symbolic cohesion to his power.

This practice is well reflected in the traditions surrounding Charlemagne and his paladins. In The Song of Roland, swords appear with functions beyond metal: Joyosa dazzles, Durandarte contains relics, and both embody the legitimacy of the Carolingian order. Through the songs, these weapons were transformed into narrative vectors that transmitted chivalric and religious values to later generations.

Joyosa: The Imperial Radiance

Joyosa (or Joyeuse, which can be translated as “the joyful” or “the jubilant”) is the sword that tradition directly associates with Charlemagne. In the epic poem The Song of Roland, it is described as a blade that shines like the sun, capable of changing color up to thirty times a day and protecting its bearer from poisons. These properties, though fantastic, serve to emphasize the idea that the emperor and his sphere were under exceptional divine care.

Legend also attributes to Joyosa a connection with Christian relics: the hilt is said to contain the tip of Longinus’ spear, which pierced Christ’s side. According to popular tradition, the sword was forged by the blacksmith Galas and took three years to complete around 802 AD, linking it to the heyday of the Carolingian reign.

Is the Joyosa at the Louvre the authentic sword?

The Joyosa preserved today in the Louvre and, formerly, in the Abbey of Saint-Denis, was used —real or symbolically— in coronation ceremonies of French kings for centuries. However, its historical authenticity is a matter of debate. The current Joyosa is a composite piece made up of elements from different eras and reconstructions:

- The pommel dates from the 10th-11th centuries and includes motifs reminiscent of Scandinavian art.

- The hilt’s cross, with two winged dragons, corresponds to the second half of the 12th century.

- The grip is dated between the 13th-14th centuries.

- The blade is of Oakeshott XII style, typical of the Middle Ages, but its final assembly and later renovations complicate a single dating.

This chronological collage does not invalidate its symbolic value: for centuries, the possession of Joyosa served to legitimize dynasties. Although it is probably not Charlemagne’s original sword, its function as an emblem of sovereignty makes it one of the most reproduced and revered pieces in the European imagination.

Durandarte: The Paladin Roland’s Sword

Durandarte (Durandal) is the companion of the hero Roland in The Song of Roland. The epic presents Roland as the emperor’s nephew and one of the twelve paladins who embodied the youth and vigor of Frankish cavalry. Durandarte appears as an indestructible sword, containing sacred relics in its hilt —a tooth of Saint Peter, blood of Saint Basil, hairs of Saint Denis, and a fragment of the Virgin’s mantle—. These inclusions emphasize the weapon’s sacredness and the aura of the Carolingian paladins.

Roland’s Breach and the Myth in the Landscape

Tradition holds that, after the defeat at the Battle of Roncesvalles (778), Roland tried to destroy Durandarte so that it would not fall into enemy hands. When he struck the sword against a rock, he did not break it but caused a crack that is now known as Roland’s Breach in the Pyrenees. According to legend, the sword was thrown and became embedded in a cliff near Rocamadour. A sword linked to this tradition is exhibited in the Cluny Museum, although —as is the case with Joyosa— absolute authenticity is difficult to prove.

Roncesvalles: Real History and Epic

The Battle of Roncesvalles in 778 is a historical event that, due to its drama and repercussions, became literary material. In reality, the Carolingian troops suffered an ambush by the Basques who attacked the logistical rearguard of the army. In the epic, the event transforms into a heroic battle where Roland and his paladins fall in combat against a gigantic Saracen army. This poetic re-elaboration served to build heroic models and reinforce the legitimacy of the Carolingian dynasty.

Joyosa and Durandarte in the Symbolic Construction of Power

Both swords show how materiality (an object, a forged blade) can become a political symbol. For medieval monarchs, claiming Charlemagne’s heritage meant more than a genealogy: it was appropriating a symbolic legacy that legitimized sovereignty. Joyosa functioned exactly in that direction: although its facture is composite, its use in coronations connected new kings with the Carolingian imperial aura.

Durandarte, for its part, embodies the ideal of the sacrificed knight and links the figure of the exemplary vassal to the protection of Christianity. The weapon ceases to be a weapon to become a witness and relic: in its hilt are kept fragments that serve as physical proof of a connection with the sacred.

Other Legendary Swords: European Context

Legendary swords are not exclusive to the Carolingian tradition. Throughout Europe, objects with similar stories appear: Excalibur from the Arthurian cycle, the swords of El Cid (Tizona and Colada), the Curtana of the British crown, or the Lobera of Ferdinand III. These weapons share traits: names that individualize them, accounts of miraculous or hagiographic origin, and a role in legitimation rituals.

- Joan of Arc sought a sword “from heaven” that was found in Saint Catherine of Fierbois.

- The inlaid sword of San Galgano in Tuscany recalls the theme of conversion and dedication.

- Excalibur and its link with sovereignty illustrate the relationship between symbol and dynastic power.

Where to See, Study, and Buy Replicas

If you want to see a piece that has historically been associated with Joyosa, the Louvre has the sword that was used for centuries in royal ceremonies. The Cluny Museum in Paris also preserves pieces related to the tradition of Durandarte. These museums allow a closer look at the materiality and restorations that have modified the pieces over time.

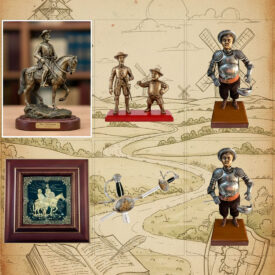

For those who desire a replica or a collector’s item, the current offer is wide: reproductions of Joyosa and Durandarte, swords inspired by the Carolingian style, and handcrafted pieces made with historical criteria. If you are interested in acquiring a quality replica, you can find options in our online store, where we select reproductions that respect proportions, decorations, and styles based on medieval sources.

Tips for choosing a historical replica

- Define purpose: decoration, historical reenactment, or use in recreational fencing.

- Materials: look for good quality carbon or stainless steel and check the temper.

- Proportions: Carolingian swords usually have relatively short and robust blades compared to later models.

- Finishes and details: hilts with motifs inspired by the High Middle Ages, crossguards with animal or geometric motifs.

If you are unsure about which replica suits your needs, our online store offers advice to select the appropriate piece according to use and budget.

Modern Research and Dating Techniques

The analysis of historical swords combines object history, archaeometry, and conservation. Techniques such as thermoluminescence dating (in associated ceramic elements), metallographic analysis, observation of forges, and decorative styles allow pieces to be placed in approximate periods. In the case of Joyosa and Durandarte, the mixture of elements from different eras requires a critical reading: many pieces we see today in display cases are the result of restorations and recompositions carried out between the Middle Ages and the Modern Age.

Studying these historical firearms (and swords) requires an interdisciplinary approach: art historians, archaeologists, conservators, and metallurgy specialists work together to trace plausible material biographies.

The Cultural Value of Charlemagne Swords

Beyond their craftsmanship, Charlemagne swords are vectors of cultural identity. They represent a bridge between historical fact —a man who ruled a vast territory— and the symbolic representation of that power. In historical festivals, museums, and private collections, Joyosa and Durandarte continue to fuel narratives about legitimacy, heroism, and faith.

Contemporary reproductions allow historians, artisans, and enthusiasts to experience the shape and weight of a Carolingian sword, which in turn enriches the understanding of medieval combat, ergonomics, and traditional forging techniques.

What do these legends teach us today?

By analyzing Joyosa, Durandarte, and other legendary weapons, we understand how societies construct symbols to sustain political and religious narratives. A sword that shines or contains relics not only affirms the exceptionality of its bearer but also acts as a pedagogical device: it teaches what is valued at the time —valor, piety, loyalty, and connection with the divine.

Furthermore, the persistence of these stories demonstrates the power of oral tradition and literature to transform specific events (an ambush in Roncesvalles) into a foundational myth that legitimizes cultural and political orders.

For those approaching from collecting or reenactment, these pieces offer a sensory and educational experience: handling a well-made replica allows one to imagine the maneuvers and sensations of medieval combat.

Final Reflection

Charlemagne’s swords —Joyosa and Durandarte— are much more than weapons: they are symbols that condense faith, power, memory, and narration. Even when critical history shows that the preserved pieces are often composites and restorations, their influence as icons endures. Visiting museums, studying the pieces, and, for those interested, acquiring replicas in our online store, are ways to connect with that material and symbolic heritage that still illuminates part of European identity.