The sword, an ancient weapon and a timeless symbol, has accompanied humankind through battles, duels, and rituals, reflecting culture, status, and art across centuries. Yet few swords encapsulate an era as perfectly as the rapier, the iconic blade that became the hallmark of the Spanish Golden Age and European fashion. Its presence in the civil attire of knights and nobles was not merely a mark of distinction but also a vital tool for personal defense in an age where honor was often decided by steel.

What is a Rapier? Its Origin and Evolution

The term “rapier” is of Spanish origin, appearing as early as the “Coplas de la panadera” by Juan de Mena (1445-1450) and the “Inventory of the Duke D. Álvaro de Zúñiga” (1468). It was so called because it was carried as a fashionable accessory, an essential part of civil dress for men of the era. Its influence was so great that the term quickly spread throughout Europe, being adopted in France as “la rapière” and in England as “rapier,” reflecting Spain’s prominence in the development and diffusion of this weapon type.

The rapier emerged in Spain in the 15th century, evolving from one-handed medieval swords such as the Italian spada da lato. Initially, these swords were suitable for both thrusting and cutting, with broader and sturdier blades ideal for a combat style mixing slashes and thrusts. However, as fencing increasingly favored the thrust (point attack) over the cut, the rapier became specialized. It transformed into a straight-bladed weapon, exceptionally long and narrow, sometimes exceeding a meter in length and weighing around a kilogram. This evolution responded not only to changes in combat technique but also to the need for a more agile and discreet weapon for daily civilian use.

Its period of greatest splendor stretched from the mid-16th century through to well into the 17th century, marking an age of profound change in combat and attire. During this time, the rapier became an omnipresent feature in the streets of European cities, from Madrid to London. Despite its civilian prominence and association with duels of honor, the rapier was primarily a personal defense weapon for individual encounters, not as suitable for military combat in closed formations, where shorter, sturdier swords remained favored.

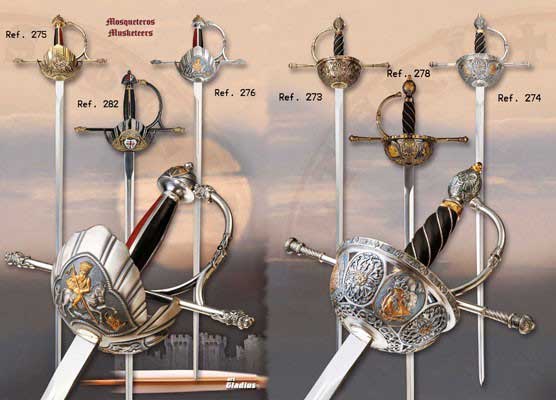

Types of Hilts: Protecting the Hand, Defining the Style

The rapier stands out not only for its blade but also for its elaborate and complex hilt—the part that protects the grip and, crucially, the fencer’s hand. Over its history, these hilts evolved to offer ever greater and more sophisticated protection, giving rise to the most characteristic and visually striking types: swept, shell, and cup hilts. Each design was both defensive and an artistic expression reflecting the status of its owner.

Swept-Hilt Rapier: Intertwined Elegance

This is the oldest and one of the most iconic hilts, appearing at the end of the 15th century. It is characterized by narrow, elongated crossguards that intertwine, forming arcs and several rings, creating an intricate and visually impressive handguard. This design, known in English as swept hilt for its elegant, curved lines, offered partial protection for the hand, as an opponent’s tip could still slip through the spaces. They were common in southern Europe and were the type most used in the conquest of the Americas, accompanying conquerors on their expeditions.

Swept hilts offered superior protection compared to the simple crosses of medieval swords, but their open design meant the hand remained vulnerable to precise thrusts. Modern experts sometimes classify swept hilts by coverage level, from “quarter hilt” (with a lower side ring for minimal protection) to “full hilt” (the most elaborate, with multiple rings and a complete knuckle guard). The complexity of the sweeps was both functional and aesthetic, letting craftsmen show off their skill and creativity.

A magnificent example of the beauty and functionality of this type of hilt is the Swept-Hilt Rapier with Bone Grip, a piece that evokes the elegance of the period.

Here is another beautiful swept-hilt rapier, highly representative and historically symbolic—such as the Colada Sword of El Cid Campeador, a replica that honors the legend of one of Spain’s greatest heroes. While the original was not a true rapier, its swept-hilt design in this recreation pays tribute to the era’s aesthetics.

Shell Guard Rapier: Practical Protection

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, as fencing became more tip-focused and thrusts grew quicker and more precise, the need for greater hand protection became evident. Thus, small metal plates (shells) were added between the rings of the swept hilt. Over time, these shells became one solid piece, often shaped like a scallop or crescent, joined to the sword’s cross by arms. This simple but effective design offered solid defense against hand-directed thrusts.

This hilt is typically Spanish, known for its practicality, sturdiness, and great protective efficacy. It was hugely popular, with specimens found from 1640 to 1790, demonstrating its durability and the preference for its functional style. In the Anglo-Saxon sphere, it is sometimes called “Bilbo,” a term connected to the export of swords from Bilbao, a major Spanish arms production center. The shell guard represented a crucial transitional step toward complete hand protection, without the visual complexity of the cup hilt.

Cup-Hilt Rapier: Maximum Defense and Detailed Art

Contemporary with the shell guard, the cup hilt arose in the first third of the 17th century and remained popular into the early 18th. Its goal was maximum hand protection, using a semicircular iron or steel piece in the form of a “cup” that completely covered the back of the hand. This cup was joined to the crossguards and handguard, creating an impenetrable barrier against an opponent’s thrusts. Spanish cup-hilted rapiers are often distinguished by their exceptionally long crossguards, providing extra hand protection and a unique balance to the weapon.

A distinctive feature of Spanish cups is the “rompepuntas,” an outward-curved edge designed to catch or even break the opponent’s tip—an ingenious defensive innovation. The cup could be plain, intricately chiseled, or pierced, often with lace-like designs that were true works of art, acid etchings, or with silver and gold finishes that enhanced its beauty and prestige. While Milan and Naples were major production centers, cup-hilted swords made in Toledo, Spain, were especially renowned for their unparalleled blade quality and mastery of hilts, becoming a reference for excellence.

Spanish cups tended to be less deep and smaller in diameter than Italian ones, suiting a particular fencing style. They often included an internal “guardapolvo,” a piece of cloth or leather protecting the hand from dirt and moisture. This hilt type represents the apex of rapier evolution in terms of protection and ornamentation, brilliantly combining function and art.

A fantastic model of a cup-hilt rapier, exemplifying the mastery of swordsmiths, is the classic Spanish Cup-Hilt Sword—a piece both functional and an authentic work of art.

Besides these three main types, other variants existed, highlighting the diversity and experimentation in rapier design. Among them are the Pappenheimer, with swept guards and two pierced shells offering robust protection and a distinct style, and lantern swords with symmetrical cups and rings connected by intertwined quillons, creating a complex, highly defensive structure. These variants reveal the constant pursuit of perfection in rapier design and utility.

Rapier Fencing: Art, Geometry, and Dueling

Wielding the rapier transcended brute strength, becoming an art requiring skill, precision, and, in Spain’s case, a deep understanding of geometry and mathematics. In the 16th and 17th centuries, two main fencing schools dominated Europe, each with its own philosophy and distinctive techniques: the Italian school, famed for its elegance, and the Spanish school, known as the Verdadera Destreza, for its scientific rigor.

Spanish Verdadera Destreza: Philosophy and Geometry in Combat

The Verdadera Destreza was a revolutionary fencing system developed by Spanish knight and philosopher Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza in the mid-16th century. His seminal treatise, De la Filosofía de las Armas y de su Destreza y la Aggression y Defensa Cristiana (1569), laid the foundation for a universal combat method based on geometric and mathematical principles. It was not only about physical movements or brute force, but a deep study of angles, distances, and movement around the adversary to gain an inescapable advantage. This intellectual approach elevated fencing to the status of a science, distinguishing it from more empirical styles.

Among Carranza’s disciples and followers, notable figures include Luis Pacheco de Narváez (Master of Fencing to Philip IV and author of many treatises expanding on his mentor’s work), Francisco Lorenz de Rada y Arenaza, and other masters like Luis Díaz de Viedma and Simón de Frías. Such was the reach of Verdadera Destreza that even Portuguese and Dutch authors, like Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo and Gérard Thibault d’Anvers, incorporated its principles in their own treatises, adapting and spreading them across Europe.

Key features of Verdadera Destreza include:

- Right Angle Stance: The weapon arm is extended in a straight line toward the opponent, forming a 90-degree angle with the ground. This position sought maximum blade reach and control.

- Use of Geometry: Movements are based on circles and imaginary lines traced in space, letting the fencer position and attack efficiently, minimizing risks and maximizing opportunity. The “circle of Destreza” was fundamental to understanding attack and defense distances and angles.

- Thrusts and Slashes: Although the system used both the blade’s tip and edge, the thrust was paramount and seen as the most efficient, decisive attack, given the rapier’s specialization.

- Blade Graduation: The blade was divided into ten or twelve “degrees of strength” from tip to hilt, indicating each part’s effectiveness in pressing against the opponent’s sword. This allowed precise blade control in close combat.

The Italian School of Fencing: Elegance and Precision

The Italian school, contemporary and highly influential throughout Europe, stood out for its refined and elegant style, often in contrast to the geometric rigidity of the Spanish Destreza. Masters such as Ridolfo Capo Ferro (author of Gran Simulacro dell’Arte e dell’Uso della Scherma, 1610) and Salvatore Fabris (author of Lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme, 1606) were prominent figures whose teachings spread widely. Their treatises taught the use of the rapier alone or with a dagger or cloak, offering a repertoire of versatile techniques adaptable to various situations.

Key differences with Spanish Verdadera Destreza include:

- Low Guards: Italian fencers often adopted positions with bent knees and slightly inclined body, allowing a lower center of gravity and more agile movements.

- Direct Line: Actions were performed along an imaginary straight line connecting the fencer with the opponent, prioritizing direct penetration and speed.

- Thrust Focus: While cuts existed, thrusts were predominant and most valued for their effectiveness in duels.

- Longer, Thinner Blades: Italian rapiers tended to have longer, thinner blades than the Spanish, favoring long-distance thrusts and speed.

- Blade Graduation: The blade was divided into two, four, or five parts (for instance, forte and debole for Capo Ferro; prima, seconda, terza, and quarta for Fabris), indicating the sections best for offense or defense.

Combinations and the Practice of Historical Fencing (HEMA)

The rapier was often paired with a left-hand dagger designed to complement its movements. This dagger, usually matched to the rapier, was crucial for defense (to parry thrusts) and for binding techniques to immobilize the opponent, creating openings for the final thrust. Spaniards, famous for their dexterity with rapier and dagger, even employed geometry to level the field between right- and left-handed fighters, demonstrating the system’s sophistication.

Today, Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) allows enthusiasts worldwide to recreate and practice these skills based on ancient treatises. “Blunt weapons”—steel replicas without an edge and with a protected tip—and modern protective gear (masks, gloves, padded jackets) are used for safe sparring. HEMA practice goes far beyond mere technique: it encourages respect for opponents, deep weapon control, and prioritizes avoiding harm while ensuring defense. “Meets” between fencing clubs are a vibrant facet of this community, where interpretations, techniques, and a love for the sword’s art and history are shared, keeping an age-old tradition alive.

The Social Role and Craftsmanship of the Rapier

The rapier was not just a weapon; it was a statement of intent, a tangible symbol of status and honor in a society where appearance and reputation were paramount. To own and wear it on the belt—together with cloak and hat—was a clear marker of social status, courage, and honor. Initially restricted to nobility and knights, its use gradually extended to intellectuals, the bourgeoisie, and soldiers, partially democratizing this mark of distinction, though always retaining its aura of prestige.

However, the rise of the rapier and attendant duels led authorities to regulate its use, worried about violence and social disorder. The Council of Trent in 1563 already condemned reliance on the sword to defend honor, aiming to temper dueling culture. 16th and 17th century Spanish laws focused on limiting the excessive length of blades, setting a “five-fourths of a vara” (about 112 cm, including the hilt) maximum for swords, executioners, and rapiers, to avoid disproportionately long, dangerous weapons on the street. Overly sharp and deadly points, such as “alesna” or “aguja espartera” types, were also banned as “malicious” and fit only for killing. Breaching these rules could result in severe penalties, including fines, prison, and confiscation or destruction of the sword, reflecting how seriously authorities took control of such weapons.

The Mastery of Spanish Swordsmiths: A Legacy of Quality

Despite the fame often attributed exclusively to Toledo, rapier production in Spain was vast and varied, with numerous high-quality centers across the peninsula. Spanish swordsmith mastery was recognized throughout Europe, and their blades were highly valued for their resilience and flexibility.

- Toledo: Undeniably the most famous and prestigious center, producing all kinds of blades, including cup-hilted rapiers and others beyond the narrowest types. Toledo’s sword-forging tradition dates back to Roman times, and its tempering secrets were jealously guarded.

- Valencia: An important production center since the 14th century, with swordsmiths and hilt-makers marking their blades with inscriptions like “IN VALENCIA ME FECIT” to indicate origin and quality. Valencian work was known for refinement and ornate hilts.

- Vizcaya (Biscay): Including Bilbao, Tolosa, and Mondragón, this area was a natural arms center thanks to abundant iron, coal, and wood. Tolosa was especially renowned for tempering quality, and Bilbao itself exported great numbers of swords, giving its name to “Bilbo” hilts in the English-speaking world. Durango also stood out for exporting hilts, highlighting regional specialization.

- Zaragoza and Barcelona: Both cities boasted active guilds of swordsmiths, hilt-makers, and gilders, producing high-quality blades and especially elaborate hilts reflecting the artistic taste of the era. Their workshops were innovation and design hubs.

- Seville: Showed great specialization, with craftsmen devoted to specific parts such as sword pommels, ensuring more efficient, higher-quality production for each component.

Making a rapier was a complex and laborious process, requiring great skill and expertise. The blades were forged from two metals: a “mild iron” (low-carbon steel) core, surrounded by high-carbon steel, joined through meticulous hammering and folding. Tempering—the art of which was closely held and often passed down generations—gave the blade a flexible core to prevent breakage and an extremely hard, wear-resistant exterior. The handles, often wood, were wrapped with metal threads (iron, copper), or, on high-end models, with silver, gold, or even silk, and could be carved or decorated using techniques like damascening (inlaying precious metals), bluing (for darkening metal), and chiseling—making each rapier a unique piece of craftsmanship.

The Legacy of the Rapier

The rapier, especially the Spanish one, was a dynamic element that adapted to the tastes, fashions, and needs of its time. Its beauty and functionality made it a reference weapon, and despite its decline in military use with the rise of firearms, it maintained its status as the indispensable companion of the gentleman—a symbol of his identity and honor. Its evolution from a weapon of war to a fashion and self-defense accessory testifies to its versatility and adaptability.

Although few ancient rapiers are well preserved—due to reuse, historical conflicts, and the passage of time—their study allows us to understand an essential part of the Spanish Golden Age and the richness of European fencing. The rapier is more than a museum piece; it is a testament to the ingenuity, art, and culture of a fascinating era—an echo of duels of honor, court intrigues, and daily life in a society that valued skill and elegance.

If you are fascinated by the history and elegance of these legendary weapons and want to own a piece that captures the spirit of the Golden Age, at Medieval Shop we offer a wide variety of the highest quality and design rapiers, crafted by the world’s best swordsmiths. You will find models with the iconic cup hilt and the intricate swept hilt, perfect for collectors, historical fencing enthusiasts, or simply those who appreciate art and history. Discover the beauty and craftsmanship of these magnificent swords and bring a piece of history into your home.