What lies behind the brilliance and legend of the sword that accompanied Francis I? In this piece, we explore the forging, the ceremonial, and the historical adventures of a parade sword associated with the king who embodied the French Renaissance. I will accompany you from the Toledan forge to the Battle of Pavia and the political vicissitudes that transformed this object into a trophy and a symbol.

You will learn to recognize its distinctive features, understand its symbolic meaning in the Renaissance court, and follow its documented trajectory through a detailed chronology. You will also find technical comparisons, anecdotes from the battle that marked its destiny, and answers to the most frequent questions.

Origin and Manufacture: Trades, Workshops, and the Artisan’s Hand

Swords destined for Renaissance aristocracy combined utility with splendor. The piece attributed to Francis I fits this tradition: a parade sword, conceived for courtly ostentation as much as for advancing the sovereign’s image in processions and ceremonies.

Its blade, according to documentary tradition, was forged and tempered in renowned workshops in Toledo; the hilt and guard reflect Mediterranean and Italianate decorative patterns that circulated through European courts between 1500 and 1515.

Francis I and the Trajectory of his Ceremonial Sword: Milestones and Movements

Below is a chronological sequence of the vital events of Francis I of France and the documented history of the ceremonial sword attributed to him, indicating relevant context and details.

| Date/Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Manufacture and Early Indications | |

| c. 1480 – 1515 | Manufacture of the ceremonial sword: a gala example of medieval style. The absence of the royal crown on the salamander indicates it was made before Francis I’s accession to the throne. |

| c. 1505 – 1510 (approx.) | Specific Dating: the blade of the gala sword is attributed to Piero Antonio Cataldo (or Chataldo), a swordsmith of Italian origin. |

| Life and Reign of Francis I | |

| 1494 (September 12) | Birth of Francis I in Cognac (France). Known as the Knight King and Father and Restorer of Letters. |

| 1515 (January 25) | Consecration of Francis I as King of France in Reims Cathedral, succeeding Louis XII. |

| 1515 | Victory in the Battle of Marignano, which allowed Francis I to recover the Milanese (Lombardy) and alter the balance in Italy. |

| Campaigns, Defeats, and Capture | |

| 1521 | Occupation of Navarre by French forces alongside troops of Henry II of Navarre, taking advantage of the War of the Communities in Castile. |

| June 1521 | Battle of Noáin: decisive victory for Charles V which allowed the recovery of Navarre; part of the lost French artillery may have later served to equip fortresses such as Pamplona or San Sebastián. |

| 1521 – 1526 | Four Years’ War: campaigns between Francis I and his allies (Henry II of Navarre, Republic of Venice) against Charles V and his allies (including Henry VIII and the Papal States). |

| 1525 (February 24) | Battle of Pavia: French defeat in Milan; much of the army killed or dispersed and capture of Francis I himself. |

| 1525 (post-Pavia) | Capture of the King and booty: Francis I is taken prisoner. According to tradition, the combat rapier and the right glove were surrendered as symbols of submission. The ceremonial sword (not the combat one) would have been taken from the king’s tent by Colonel Juan de Aldana. |

| 1525 (post-Pavia) | Delivery of the combat rapier: Diego de Ávila, a man-at-arms, would have received the rapier (saddle rapier) and the right glove as a symbol of the monarch’s surrender. |

| 1526 (January 14) | Treaty of Madrid: Francis I, prisoner in Madrid, signs conditions in which he renounces claims in Italy and other territories. |

| Death and Destiny of the Sword | |

| 1547 (March 31) | Death of Francis I in Rambouillet, France. |

| 1585 | Acquisition by the Spanish monarchy: Marco Antonio Aldana (son of Juan de Aldana) delivers the ceremonial sword to Philip II in exchange for an annual pension; the piece enters the Spanish royal collection. |

| 1585 – 1808 | Stay in Spain: the sword remains in the Royal Armory of Madrid for 283 years within the Spanish royal collection. |

| Transfer to France and Exhibitions | |

| March 1808 | Request from Napoleon/Murat: Marshal Joachim Murat (Duke of Berg) requests Ferdinand VII to hand over the sword as a gesture of goodwill. |

| March 30–31, 1808 | Delivery to France: Ferdinand VII orders the delivery of the ceremonial sword to Murat; the piece is sent with pomp to the Duke of Berg. |

| Post-1808 – 1815 | Transfer and Custody: the sword accompanies Napoleon I in his study cabinet in the Tuileries until 1815. |

| 1852 | Exhibition at the Louvre: the sword is part of the Musée des Souverains (Museum of Sovereigns) in the Louvre. |

| During the reign of Isabella II (19th century) | Commission of replica: as the original could not be recovered for the Royal Armory, Francis of Assisi (consort of Isabella II) commissioned Eusebio Zuloaga for a replica that cost 4,000 reales for the Spanish collection. |

| 1872 | Relocation to Paris: the sword is transferred to the Artillery Museum (Musée de l’Armée), where it will be assigned to the military collections. |

| Current Situation and Commemorations | |

| Present Day | Location: the ceremonial sword attributed to Francis I (identified as MAP J 176 or inv. 993/J 376) is located in the Armory of the Musée de l’Armée (Paris). |

| 2024 (March 1) | Academic Commemoration: communications are published recalling the Battle of Pavia, almost 500 years after the event. |

| 2025 (July 27) | Publication Date: update of the article that recounts the history of the sword and its documentary trajectory. |

What the Sword Was Like: Shape, Inscription, and Ornament

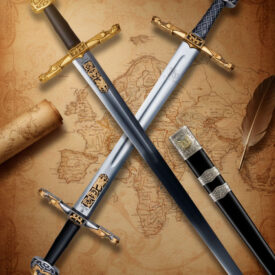

The description that has come down through tradition and documents points to a long and wide blade, characteristic of a gala piece that prioritizes presentation. On both sides of the blade, traced motifs and a three-armed cross are observed in the decorative part.

The description that has come down through tradition and documents points to a long and wide blade, characteristic of a gala piece that prioritizes presentation. On both sides of the blade, traced motifs and a three-armed cross are observed in the decorative part.

Guard and Hilt: bronze guard with straight quillons decorated in white enamel, bearing the legend “FECIT POTENTIAM IN BRACHIO SVO” (“He did mighty deeds with his arm”). The hilt combines volutes and foliage motifs; the spherical pommel appears enameled in red with the salamander of Angoulême, the king’s personal symbol.

Approximate measurements handled in bibliography and catalogs: total length close to 98 cm and weight around 1.5 kg, which positions it as a ceremonial sword yet manageable in the hands of a trained monarch.

Materials and Technique

Blade in forged and tempered carbon steel, guard in gilded bronze and enamels of Italian tradition; painted and chased decoration. The combination reveals the influence of Hispano-Toledan workshops and Italian goldsmiths who worked for European courts.

The Battle of Pavia and the Symbolic Gesture of Surrendering the Sword

On February 24, 1525, the Battle of Pavia became a turning point for the French monarchy. After an initial phase favorable to the French, the appearance and effectiveness of the imperial arquebusiers tipped the scales.

Francis I personally led a cavalry charge, believing he would defeat the opposing forces. When surrounded and wounded, the king’s surrender materialized through ritual gestures: the surrender of the combat rapier and the right glove were recognized symbols of submission.

According to tradition, in addition to these emblems, the ceremonial sword linked to the king was taken as booty and passed into the hands of imperial officers, thus beginning its journey through royal collections and arsenals.

Why was the sword more than steel?

In Renaissance courts, the monarch’s sword symbolized justice, order, and protection. Losing it was not just a military defeat: it was a public humiliation that projected political weakness. That is why war trophies and their exhibition had high propaganda value.

The symbolic or political rescue of a sword could be used centuries later to legitimize diplomatic gestures or commemorative acts, as occurred with the transfers of the piece between Spain and France during the Napoleonic period.

Comparative: Original, Replicas, and Historical Versions

When studying objects with a long documentary history, it is convenient to separate the original from the replicas and copies commissioned in later eras. Below is a comparative table that helps distinguish technical and contextual features.

| Version | Approximate Length | Material | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attributed Original | 98 cm (blade) | Carbon steel (blade), bronze and enamels (guard) | Dated c.1510–1515; gala piece linked to Francis I |

| Replica (Eusebio Zuloaga, 19th c.) | Similar to the original | Contemporary steels and forging metals | Commissioned for the Spanish collection during the reign of Isabella II |

| Historical Copy (18th–19th c.) | Variables | Period materials | Examples for commemorative or museum purposes |

The Political Trajectory: From Trophy to Diplomatic Symbol

The sword, after its capture, was incorporated into the Spanish royal collection and kept for centuries. Its status oscillated between weapon and diplomatic relic, and in 1808 it once again acquired public relevance when its transfer was decided as a political gesture.

This type of asset served both to remember victories and to rewrite national narratives. Recovering or returning a sword could be read as an act of reconciliation or hegemonic power, depending on the context.

Lessons for the Collector and Scholar

-

Documentation: attribution requires concordance between decoration, inscriptions, and documentary provenance.

-

Material Analysis: metallographic tests and forging studies help confirm chronologies.

-

Symbolic Context: a royal sword may have offered ceremonial service and been aesthetically adapted over time.

Maintenance and Conservation (Practical Notes)

Although today replicas and copies are worked with, knowing the care of a historical blade helps to understand its value. For a carbon steel piece, oils that prevent corrosion and greases for prolonged storage are recommended.

| Type of Oil | Main Characteristics | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|

| Mineral Oil | High penetration, does not degrade or attract dirt | Regular protection and maintenance |

| Camellia Oil | Natural, acid-free, non-volatile | Antioxidant protection, lubrication |

| Lithium Grease | Dense, durable, does not evaporate | Prolonged storage, protection |

- Hispaniensis

-

- Blade Length: 60–68 cm (approx.)

- Era: 3rd–1st centuries BC

- Tactical Use: Versatile: powerful cuts and thrusts in close formations.

Solve Your Doubts About Francis I’s Sword

What are the distinctive characteristics of Francis I’s sword?

The sword of Francis I is characterized by being a parade sword of medieval style manufactured between 1480 and 1515, designed and personalized for pomp, with a bronze guard with straight quillons bearing the legend in white enamel: “FECIT POTENTIAM IN BRACHIO SUO” (“He did mighty deeds with his arm”). Its hilt is delicately decorated with gold and enamels, and the spherical pommel is enameled in red with a striking foliage and the salamander of Angoulême in flames. The blade is made of carbon steel forged and tempered in Toledo, measures approximately 98 cm and weighs 1.5 kg. This sword was used as a ceremonial weapon and was linked to key historical moments, such as the capture of Francis I in the Battle of Pavia in 1525. Furthermore, it was a symbol of power associated with the King of France and its style reflects a combination of functionality and decorative luxury.

How was Francis I captured in the Battle of Pavia?

The capture of Francis I in the Battle of Pavia (February 24, 1525) occurred when, at a critical moment in the combat, the French king personally led a cavalry charge at the head of 900 men to try to break the imperial troops, believing they were almost defeated. However, as he advanced, he found himself surrounded and attacked by enemy forces, including imperial arquebusiers firing at close range, which disorganized the French cavalry. Francis I was wounded in the arm and, after resisting with his sword for a long time, was finally captured by imperial soldiers, who surrounded him without him wanting to surrender to anyone but a general. His army was annihilated, and many of his men died or were taken prisoner.

The capture of Francis I in the Battle of Pavia (February 24, 1525) occurred when, at a critical moment in the combat, the French king personally led a cavalry charge at the head of 900 men to try to break the imperial troops, believing they were almost defeated. However, as he advanced, he found himself surrounded and attacked by enemy forces, including imperial arquebusiers firing at close range, which disorganized the French cavalry. Francis I was wounded in the arm and, after resisting with his sword for a long time, was finally captured by imperial soldiers, who surrounded him without him wanting to surrender to anyone but a general. His army was annihilated, and many of his men died or were taken prisoner.

There are different versions about who specifically participated in his capture, but it is recognized that it was a collective effort in the heat of battle, and his capture was not accidental, but the result of a desperate, close-quarters combat. The capture meant that the French king was taken prisoner and had a decisive impact on the war for control of the Milanese.

What other personal objects of Francis I are preserved today?

No specific and publicly known personal objects of Pope Francis are preserved, as it is likely that his belongings are safeguarded in Vatican archives or donated to charitable institutions or close individuals, following his principle of humility. Unlike previous popes, his objects have not been designated as relics or for solemn exhibitions.

What was the impact of Francis I’s sword on the history of France?

The sword of Francis I had a symbolic impact on the history of France by representing the king’s defeat in the Battle of Pavia in 1525, a crucial event in the Italian Wars that marked a serious setback for the French monarchy and its hegemony in Europe. The capture of Francis I and the loss of his sword to Spanish soldiers reflected the political and military defeat against Charles I of Spain, temporarily weakening French influence in Italy and Europe.

The sword of Francis I had a symbolic impact on the history of France by representing the king’s defeat in the Battle of Pavia in 1525, a crucial event in the Italian Wars that marked a serious setback for the French monarchy and its hegemony in Europe. The capture of Francis I and the loss of his sword to Spanish soldiers reflected the political and military defeat against Charles I of Spain, temporarily weakening French influence in Italy and Europe.

This sword, forged between 1510 and 1515, was a symbol of the king’s power and prestige, but after the defeat, it passed into Spanish hands and remained in the Royal Armory of Madrid for almost 300 years, highlighting the humiliation for France and the victory of the Spanish Empire during that historical period. Its return to France in 1808 was a symbolic act related to the Napoleonic events. In summary, the sword appears as a tangible emblem of the temporary decline of French power in the 16th century due to its defeat in Pavia.

What other kings or historical leaders had similar swords?

Other kings and historical leaders who had similar swords, as symbols of power and authority, include:

- Alexander the Great, whose sword represented conquest and the expansion of empires, symbolizing his ambition and audacity as a military leader.

- Charlemagne, with his sword Joyeuse, used in coronations and a symbol of European unification under the Carolingian Empire.

- William the Conqueror, owner of an emblematic Norman sword during the Battle of Hastings, which represented the birth of his dynasty in England.

- King Arthur, whose legendary sword Excalibur symbolized divine right and the legitimacy of government.

- Viking warriors, whose robust and heavy swords represented authority and social status in Norse culture.

In addition, monarchical ceremonies such as British coronations use symbolic swords, such as the Curtana, representing justice and power etched in historical tradition. All these swords fulfill a similar function to that of the best-known royal swords in terms of symbolizing legitimacy, power, and authority.

| Type of Oil | Main Characteristics | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|

| Mineral Oil | High penetration, does not degrade or attract dirt | Regular protection and maintenance |

| Camellia Oil | Natural, acid-free, non-volatile | Antioxidant protection, lubrication |

| Lithium Grease | Dense, durable, does not evaporate | Prolonged storage, protection |

- Hispaniensis

-

- Blade Length: 60–68 cm (approx.)

- Era: 3rd–1st centuries BC

- Tactical Use: Versatile: powerful cuts and thrusts in close formations.

A Conclusion to Take With You

The history of Francis I’s sword is the story of the paradox between pomp and vulnerability: an object designed to monumentalize the king that ended up symbolizing his defeat. Beyond its material value, the piece reminds us of the role of emblems in politics and historical memory.

If you are passionate about material history, this sword is a perfect example of how an artifact can travel across geographies, hands, and narratives; and how each translation adds layers of meaning that should be read with rigor and critical insight.