In the dim light of the longship, against the mist of the fjord, the silhouette of a warrior is silhouetted against the dawn: he wears a helmet that seeks not to flaunt, but to survive. This image — both practical and symbolic — is closer to historical truth than the horned caricature that Hollywood and popular culture imposed for centuries. Here you will learn what we know with certainty about Viking helmets, how they were made, what types exist according to archaeological finds, and why certain myths endure.

From reality to myth: evolution of the Viking helmet

The following chronology compiles the archaeological, historical, and cultural milestones that explain the origin of the myth and the current reconstruction of the Viking helmet. Placing it after the hook helps to understand how public perception moved away from the evidence.

| Era | Event |

|---|---|

| Bronze Age | |

| Tundholm horned helmet | Discovery at the Tundholm site (Denmark) of a helmet with horns or “lurs”-type pieces. The misinterpretation of this find by antiquarians in the 19th century was decisive in fueling the belief that Vikings wore horned helmets. |

| Vendel Period (c. 550–800 AD) | |

| Origin of “spectacle helmets” (Vendel) | Period of origin of the so-called Vendel or “spectacle” helmets. The type of helmet to which the Gjermundbu Helmet belongs has roots in this tradition. |

| Viking Age (approx. 793–1066 AD) | |

| Design and materials of Viking helmets | Real helmets were simple and functional: forged iron, rounded or conical shapes, nasal protectors, and, in some cases, bronze decorations that would indicate status. There are also indications of helmets made of leather and leather strips. |

| Gjermundbu Helmet (10th century / circa 880 AD) | The only complete and original Viking helmet found to date. Dated to the 10th century (other sources place it around 880 AD). It was buried in a mound in Gjermundbu, Ringerike (Norway). It belongs to the “spectacle helmets” or Nordic crest type; there are ~30 fragmentary examples of this type, but only Gjermundbu is complete. |

| Other related finds | Similar helmets or remains have been found in Olomouc and St. Wenceslas (Czech Republic), Ostrów Lednicki (Poland), and oxidized remains in Tjele (Denmark) and on the island of Gotland (Sweden). |

| Contemporary representations | Runic inscriptions and illustrations from the period show simple helmets, often with a nasal protector or “spectacles.” Sources also suggest the use of lightweight materials such as leather; in general, contemporary iconography does not support horns. |

| Impracticality of horns | The presence of horns is considered impractical in combat (e.g., they hinder movements in closed formations like the “shield wall”), which reinforces the rejection of their actual use by Vikings. |

| 19th Century (Romanticism) | |

| Spread of the myth in Romanticism | The myth of horned helmets took root during the 19th century. Illustrations by Gustav Malmström (1820) for “The Saga of Frithiof” depicted Vikings with horns to accentuate ferocity; Wagner’s “Ring Cycle” also reinforced this iconography. The word “Vikingr” reappeared in English Romanticism as “viking,” giving rise to the idealized conception of the modern Viking. |

| 20th Century | |

| Film “The Viking” (1928) | Early example of cinema that used the iconography of the horned or winged helmet, contributing to the popular spread of the stereotype. |

| Discovery of the Gjermundbu Helmet (1943) | The discovery in a burial mound in Gjermundbu (Norway) provides the only complete example of a known Viking helmet, crucial for the study of real Viking weaponry. |

| Film “The Vikings” (1958) | Film production that further popularized the image of the Viking with a horned or winged helmet in popular culture. |

| Popular culture and comics (mid- and late 20th century) | Series and comic strips like “Vicky the Viking” and “Hägar the Horrible” (created in 1973) solidified the image of the Viking with a horned helmet in the popular imagination. |

| More critical recreations (late 20th century) | Some later cinematic productions, such as “The 13th Warrior” (late 20th century), avoid horns on helmets, although they may incur other anachronisms. |

| Present Day (21st Century) | |

| Academic and popular science review | Modern archaeological and historical investigations continue to debunk the myth of horned helmets and clarify the actual shapes and materials used by Nordic warriors. |

| Contemporary television | Series like “Vikings” (premiered in 2013) show a representation closer to the evidence (avoiding horns on helmets), although they maintain certain creative licenses and anachronisms in other elements. |

How they really were: shape, materials, and functions

The Viking helmets we know from archaeology and sources are, above all, tools for survival. Their design prioritized skull protection, vision, and breathing, not ostentation. Below are described the most frequent features and the logic behind each element.

- Materials: mainly iron for rigid parts; leather and leather strips for linings and fastenings; in some cases, bronze for decoration.

- Shapes: rounded or conical to deflect impacts; band helmets (spangenhelme) assembled with strips; and “spectacle” models with nasal and ocular protection.

- Protections: nasal protector (nasal), sometimes cheek flaps, and, on rare occasions, reinforced forehead plates.

Main types and their identification

The classification is based on findings and historical typology. Below, the most frequently appearing types in specialized literature are compared.

| Type | Characteristics | Approximate period | Usage and context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gjermundbu | Complete “spectacle” helmet with nasal protector; forged iron, riveted pieces. | 9th–10th centuries | Probably used by high-status combatants; unique complete archaeological example. |

| Spangenhelm (band helmets) | Constructed with several plates joined by metal bands; lightweight and repairable. | 6th–10th centuries | Widespread use in Europe; good protection/weight ratio. |

| Conical or one-piece | Forged from a single sheet or hammered into a conical shape to deflect blows. | 7th–10th centuries | Warriors who prioritized robustness and simplicity, easy to produce. |

| Vendel / “Spectacle” Helmet | Decorated, with guards around the eyes; influencing early Gjermundbu. | Vendel Period (c. 550–800) | Possible ceremonial use or by the elite; pieces of high symbolic value. |

- Gjermundbu

-

- Material: Iron, rivets, sometimes lined.

- Era: 9th–10th centuries.

- Level: Possible symbol of high rank.

- Spangenhelm

-

- Material: Plates joined by metal bands.

- Era: 6th–10th centuries.

- Level: Common, practical, and economical use.

The great myth of horns: origin and why it endured

The image of Vikings with horned helmets does not originate from archaeology, but from European Romanticism and the artistic reinterpretation of the past. Illustrations, operas, and later cinema and television created a powerful iconography: horns symbolized ferocity and “primitiveness” in the eyes of the modern public.

Why is their use in combat unlikely? Because adding large horns to a helmet is a bad tactical decision: they hinder movement in tight formations, offer points for the opponent to grab onto, and represent counterproductive weight and leverage. Therefore, material evidence and combat logic rule out this practice for everyday warfare.

Key findings: the Gjermundbu Helmet and other remains

Among the scarce remains of authentic helmets, the Gjermundbu Helmet stands out. Found fragmented and reconstructed, it forms the most solid basis for understanding the typology of late Nordic helmets. Other fragmentary finds complement the picture, but they are rare: iron corrosion and burial practices limit the survival of the material.

The value of the Gjermundbu is not only its state of preservation, but also the technical details it reveals: rivets, dome curvature, and internal fastening solutions. These details allow modern researchers and artisans to reproduce models close to the originals with functional and aesthetic criteria.

Archaeological context and geographical distribution

Although most finds come from Scandinavia, related remains have appeared in areas as remote as the current Czech Republic and Poland. This reflects Viking travel, trade, and conflict routes and how their armament technology spread or adapted locally.

Construction, blacksmithing, and decoration

To understand a Viking helmet, one must imagine the blacksmith’s workshop: fire, hammer, and the expert hand bending the iron sheet. The process sought a balance between lightness and strength. Techniques included single-piece forging, band assembly (spangenhelm), and riveting of plates.

- Forging and assembly: the spangenhelm allows quick repairs; the piece forged from a single sheet offers greater structural integrity.

- Linings: leather and fabric cushion blows and protect against moisture; chainmail was often worn in conjunction with the helmet as neck and lower head protection.

- Decoration: from engraved bronze to interior coverings, ornamentation could indicate status without sacrificing functionality.

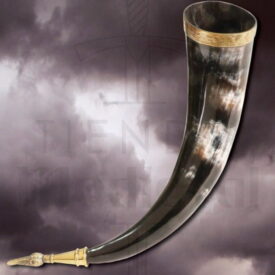

Replicas, historical reenactment, and collecting

Contemporary interest in Viking helmets has given rise to an industry of replicas ranging from decorative pieces to reproductions usable in reenactments and stage combat. The key to distinguishing between a reliable replica and a merely ornamental piece lies in the fidelity of materials and techniques.

Below you will see a random selection of products related to the Viking helmets category (replicas and accessories), designed to introduce you to the variety without replacing a critical reading of each piece.

Distributing historical images and descriptions alongside replicas helps to understand why certain elements are merely aesthetic (such as horns or exaggerated embellishments) and others replicate real solutions (nasal protectors, rivets, linings).

How to evaluate the authenticity of a replica

If you are interested in a reproduction for reenactment or private display, consider the following practical and technical criteria:

- Materials: iron or steel for the dome, leather inside, and appropriate rivets are indications of functional reproduction.

- Technique: test if it is riveted or welded; modern welding can distort the aesthetics and mechanical behavior.

- Ergonomics: it should weigh and distribute the load like an original helmet to allow its use in performances or light combat.

- Documentation: a good manufacturer or artisan provides historical references and photographs of the production process.

Responsible uses of replicas

Replicas intended for historical reenactment should be used responsibly: proper cleaning, checking rivets and linings, and use in safe contexts to avoid personal or material damage. A historical replica serves to learn, touch, and understand but not to replace archaeological study.

Quick comparison: historical helmet vs. decorative helmet

| Aspect | Historical helmet (functional replica) | Decorative helmet |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Steel/iron, leather lining | Brass, aluminum, painted finishes |

| Technique | Rivets, forging, assembly | Light welding, molded parts |

| Ergonomics | Real weight distribution, designed for use | Designed for display, often uncomfortable |

| Price (indicative) | Varies according to fidelity and materials | Generally lower but less realistic |

- Historical helmet (functional replica)

-

- Use: Reenactments, educational exhibitions, stage training.

- Maintenance: Requires metal and leather preservation.

- Decorative helmet

-

- Use: Decoration, photography, merchandising.

- Maintenance: Less demanding but less durable.

Questions that often arise among those approaching Viking history

Were warriors buried with their helmets? Did everyone have a helmet? Were they expensive? The answers are not always simple: the discovery of the Gjermundbu indicates that some high-status warriors were buried with helmets, but the scarcity of remains suggests that not every combatant had a helmet. The technology existed, but its distribution depended on social and economic status.

Why are there so few helmets? Because iron corrodes and many pieces were reused. Furthermore, burial practices varied, and in many tombs, the body was placed without equipment or with perishable elements such as leather and wood.

Understanding these limitations forces us to read each find with caution and not to extrapolate a universal pattern from isolated pieces.

Final words for those seeking authenticity

If you feel the attraction of history, always seek a balance between rigor and emotion. Value the sources, observe the technical details, and place each object in its context. Real Viking helmets tell stories of voyages, battles, and hierarchies; well-made replicas allow us to touch and understand them.

After reviewing the chronology, types, myths, and techniques, you now have the tools to distinguish legend from evidence: this is how you truly learn to look at the past.