What made medieval Italian armor legendary? In the 14th and 15th centuries, the so-called Milanese armor achieved an exceptional balance between protection, mobility, and aesthetics; a technical achievement that transformed the understanding of war and chivalric prestige. This article explores in detail medieval Italian armor: its origins, materials, key pieces, Gothic variants, and how to recognize or choose functional and decorative replicas and pieces.

Origin and manufacturing centers: Milan, Solingen, and the European tradition

The excellence in armor manufacturing during the 15th century was concentrated in centers such as Milan (Italy) and Solingen (Germany). Both poles combined metallurgical tradition with specialized workshops that worked to order, adjusting each piece to the client’s measurements without losing the basic functional pattern. The term medieval Italian armor is often associated with the so-called Milanese armor, famous for its solidity and finish.

Milan stood out for its Gothic armor workshops, known for prioritizing the combatant’s mobility without sacrificing protection. Solingen, for its part, contributed techniques and mastery in steel working that spread throughout Europe. Both cities influenced the typology of pieces — such as breastplates, backplates, and faulds — and the development of articulated solutions for critical points of the human body.

Characteristics of Italian Gothic armor

Italian Gothic armor emerged from the pursuit of stylized profiles and efficient articulations. Although they were made to order — varying in measurements and decoration — they retained a recognizable pattern: superimposed and riveted plates, sharp cuts that channeled blows, and curved elements that offered resistance against thrusts and cuts.

Metallurgical refinement allowed for the creation of lighter yet resistant plates. To protect areas less covered by plates, mail or maille was used, especially on elbows, armpits, the inner thigh, and the pubic region in certain Gothic configurations, where the absence of tassets left the crotch exposed if the knight was on foot.

Main parts and their function

- Cuirass: Consisting of the breastplate (anterior part) and the backplate (posterior part). It is the central piece that encloses the torso.

- Over-breastplate or belly plate: An additional piece on the lower part of the breastplate that reinforces the abdomen and increases protection of the lower thorax.

- Faulds and upper belly plate: The defense of the waist and abdomen, formed by articulated metallic lamellae that allow flexion and extension.

- Rerebrace: Continuation of the faulds at the back to protect the kidney area.

The connections between these pieces could be by adjustable straps or very tight rivets; in some sets, the over-breastplate and breastplate were so firmly coupled that they gave the impression of being welded, while in others the strap allowed the height to be adjusted according to the user’s figure.

Cuirass, breastplate, and backplate: anatomy of protection

Milanese armor was designed with effectiveness in mind. The breastplate and backplate are complementary elements that cover the torso, but the cuirass did not always cover the entire torso to avoid limiting breathing or flexibility. That is why elements such as the belly plate and the rerebrace were added: protection increased without sacrificing movement.

The design of the cuirass responded to tactical criteria: inclined surfaces to deflect impacts, reinforced edges to resist sharp points, and a curvature that offered structural rigidity. The correct articulation between the breastplate, over-breastplate, and faulds was key for the knight to be able to mount, dismount, and fight with relative ease.

Faulds, lames, and rerebrace: intelligent mobility

The faulds were constructed with lames—wide metal plates—riveted or joined to create a flexible belly plate. This solution allowed for the protection of the lower abdomen and, combined with the rerebrace, covered the lumbar region without constricting it. The arrangement of the lames was studied so as not to hinder horseback riding or leg movements when dismounting.

Protection of joints (elbows, knees, and shoulders) was resolved with articulated pieces: Gothic, with pointed shapes and ribs that increased rigidity and channeled blows; or more rounded in later styles geared towards heavy cavalry.

Materials and techniques: steel, reinforcements, and mail

Metallurgical evolution was decisive. Medieval Italian armor utilized increasingly thin and homogeneous steel plates, drawn and heat-treated to balance hardness and ductility. In the most exposed areas, additional treatments or layers were applied to improve impact resistance.

Chainmail under the plates protected gaps and joints. This combination — outer plates and inner mail — was an effective formula: the plates absorbed and deflected the energy of the blow, while the mail trapped fragments and covered areas that required flexibility.

Social function: from battle to parade

Armors were an expensive luxury within reach of few. Manufacturing a complete set could take several months, and depending on the level of chiseling and finishing, the time and price increased considerably. Armors not only served for war; they also played a central role in ceremonies, tournaments, jousts, and gala events.

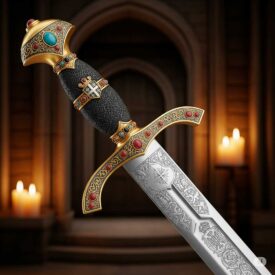

Decoration—repoussé, chiseling, engravings, and gilding—transformed the armor into a medium of identity and prestige. Highly ornamental works functioned as parade or ceremonial armors, while sets intended for battle prioritized functionality over ornamentation.

Events where Italian armor shone

- Tournaments and jousts: skill tests that required specific protection for repeated impacts.

- Passes of arms and ceremonies: exhibitions for representative and political purposes.

- Military campaigns: more austere and reinforced versions designed for real combat.

Even within the same armor, there were differentiations: removable or replaceable parts depending on the occasion (war, tournament, or parade).

Custom construction and ornamentation: the armorer’s work

The craftsmanship was highly specialized. The armorer took exact measurements of the client and designed patterns that allowed for articulated assemblies. Fine chiseling and decoration elevated the protective piece to an object of luxury. That is why the Gothic version, with ribs and fluting, was associated with both functionality and a sharp, elegant aesthetic.

Some common technical resources were:

- Ribs: reinforcements formed by folds in the plate that increase rigidity.

- Lames and rivets: resistant articulation points that allow controlled movement.

- Internal lining: textile padding that improves comfort and absorbs impacts.

Maintenance, conservation, and choosing replicas

Historical armors require care: periodic cleaning to remove moisture and prevent corrosion, greasing at connection points, and storage in dry environments. Maintenance preserves both the functionality and the historical value of the piece.

If you are looking for a replica, first decide its use: decoration, historical reenactment, or recreational combat. There are clear differences:

- Decorative: detailed finishes and less structural rigidity; ideal for display.

- Functional: constructed with thicknesses and treatments that allow for use in safe reenactments and practices.

- Historical: faithful replicas of original techniques and measurements, more expensive and sometimes made to order.

To advise you and buy pieces or sets, consult our official store: Medieval Shop

When selecting functional armor, check:

- Fit and articulation points: they must allow mobility without severe chafing.

- Steel quality and anti-corrosion treatment.

- Distributed qualities and weight: a well-designed armor distributes load and fatigue.

Custom manufacturing remains the best option if you are looking for authenticity. A standard harness can be adapted, but nothing replaces a job adjusted to your measurements.

Decoration, symbols, and cultural context

Armors were also canvases of identity: heraldry, emblems of orders, or signs of rank were depicted with chiseling or gilding techniques. In the Italian context, powerful families commissioned pieces that demonstrated power and refinement, and the Milanese workshops became preferred suppliers.

The use of ornamental resources not only accompanied the nobility: some mercenary knights or condottieri ordered armors that projected a professional and fearsome image, combining resistance with an imposing appearance.

How to read armor: identify pieces and periodize

Recognizing Italian armor involves looking at details: Gothic ribs, breastplates, faulds in the abdominal area, and the type of helmet and gauntlets. Dating is done by combining pieces and technical solutions: Gothic armor has a clear formal language, while later styles show smoother lines and rounded masses.

If you are interested in researching or restoring a piece, document measurements, workshop marks, and any decoration that allows identifying origin and workshop. A comparative study with museum specimens helps to correctly date and catalog.

Maintaining the relationship between form and function is important: a highly ornamented armor may be less practical in combat, but its historical and artistic value is unquestionable.

Medieval Italian armor represents a moment where technology, design, and social demand converged to produce solutions that continue to fascinate historians, armorers, and collectors.

If you are looking for real, functional, or decorative pieces, our recommendation is to go to professionals and specialized stores. To obtain materials and sets, you can visit Medieval Shop, where we offer options for different uses and budgets.

VIEW MORE DECORATIVE ARMORS | VIEW FUNCTIONAL ARMOR PIECES | VIEW DIFFERENT ARMOR PIECES | VIEW MEDIEVAL BREASTPLATES AND BACKPLATES

Medieval Italian armor is not just metal and measurements: it is the expression of an era that sought, through the armorer’s craft, beautiful, resistant, and body-adapted technical solutions. Knowing its pieces and its history helps both amateurs and professionals to value and preserve this heritage.