What distinguishes an epee from a saber or a foil? Imagine the chill of steel, the clash of wills, and the precision of a point that decides the assault. In this article, you will find, with clear language and historical authority, how these three modern fencing weapons differ: their design, rules, tactics, training, and equipment. You will learn to identify each modality on a strip, understand its touch priorities, and decide what physical and technical qualities each demands.

A quick glance: the three modalities in one sentence

Foil: light and flexible weapon, thrusting; valid target area: torso; points are scored only with the tip, and priority exists in attacks. Saber: cutting and thrusting weapon, very fast assaults; valid target area: waist up (includes head and arms); both tip and edge are used. Epee: heavier and stiffer weapon, thrusting to the entire body; there is no priority convention, and double touches can occur.

Origin and evolution: from dueling weapon to Olympic sport

Modern fencing originated from the martial tradition of Renaissance and 18th-century Europe, when fencing swords evolved from real combat weapons to training tools and regulated dueling. In the late 19th century, fencing was organized as a sport: foil and saber were present at the Athens 1896 Games, and epee was incorporated in Paris 1900. Since then, regulations and equipment have evolved to their current form, with electronic scoring and safety standards.

Design, construction, and measurements: technical differences

The three weapons share tempered steel and a handle designed for control, but differ in shape, blade section, grip, and hand protection. International rules set lengths and weights that condition the technique.

| Weapon | Type of hit | Valid target area | Blade section | Approximate weight | Minimum length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foil | Thrust (tip) | Torso (neck to waist) | Rectangular | ≈ 450 g | ≥ 90 cm |

| Saber | Cut and thrust (tip and edge) | Waist up (includes arms and head) | Rectangular (stiffer) | ≈ 450 g | ≥ 88 cm |

| Epee | Thrust (tip) | Entire body | Triangular | ≈ 750 g | ≥ 90 cm |

Notes on measurements and electronic control

Weight and length have tolerances and are regulated by the International Fencing Federation. Electronic scoring distinguishes touches using cables and metallic vests (in foil) and plate systems in saber; in epee, the registration combines the tip with the connection to the lame and the jacket.

How to score: priority, double touches, and conventions

Understanding the scoring rules is key to differentiating tactics:

- Foil: convention weapon. If two touches occur almost simultaneously, priority rules (or “right of way”) determine who receives the point. There are no valid double touches; the initiative of the attack must be demonstrated.

- Saber: also a convention weapon; priority is essential, and assaults are extremely fast, so the referee’s interpretation is decisive.

- Epee: no priority convention exists. If both fencers touch within a minimum margin, double touches are counted. The strategy here changes: defense and patience are usually rewarded.

Technique and style: what each modality trains

Each weapon demands a distinct set of skills. Below are the training priorities and how they influence combat style.

Foil: precision, timing, and a cool head

Foil demands a combination of mental quickness, refined technique, and rhythm control. The valid target area (torso) requires precise tip work. Foil fencers work extensively on parry, riposte, and short footwork techniques to create priority opportunities.

Saber: speed, aggressiveness, and aerial space control

In saber, action is not limited to thrusts: the edge allows cutting attacks, making distance, timing, and rhythm changes crucial elements. Bouts are short, explosive, and require anaerobic endurance and refined reflexes.

Epee: patience, distance, and total precision

Epee, by scoring the entire body and allowing double touches, turns each bout into a tactical chess match. Defense is as powerful as offense; actions are usually more measured, and distance management and split-second decision-making are rewarded.

Grips and ergonomics: the arm’s extension

The grip defines the feel and force transmission. The saber usually maintains a traditional shape, easy to grasp for quick cuts. The foil and epee feature grips more adapted to fine control, with designs that seek to turn the blade into a natural extension of the arm.

Materials, safety, and electronics

Today, weapons are made of tempered steel, and protections are designed to minimize risks. The foil uses a metallic vest connected to the touch registration system; the saber employs systems that register contact in valid areas; the epee, with its greater rigidity, also has its own electronic assembly. Safety has reduced accidents to very low levels.

Tactics and real assault examples

Theory is demonstrated on the strip. These practical examples show how the rules apply in typical situations:

- Foil scenario: a fencer attacks with a thrust aimed at the chest; the defender performs a parry and immediately a riposte which, by priority, scores the point.

- Saber scenario: a high cutting attack (head) is intercepted with a direct counterattack; the quickness of the competitor controlling the tempo decides the bout.

- Epee scenario: two fencers touch almost simultaneously; the referee registers a double touch, and both receive a point, radically changing the bout’s strategy.

How a fencer trains according to their weapon

Although there are cross-competencies, training varies:

- Foil: aiming exercises, short footwork, priority work, and attack and defense simulations.

- Saber: speed drills, change of direction, reaction exercises, and anaerobic endurance.

- Epee: distance management sessions, patient defense, wrist strengthening, and exercises for managing double touches.

Physical and mental qualities developed by fencing

Beyond technique, fencing works on:

- Speed: arm and leg speed, essential in all modalities.

- Endurance: especially in long competitions; physical preparation is key.

- Reflexes: reduces reaction time to an unexpected attack.

- Coordination and balance: leg technique is specific and requires constant practice.

- Tactics and competitor reading: knowing when to attack or wait defines the result.

Practical comparison: which weapon to choose according to your profile?

The choice depends on your personality and sporting goal:

- You seek technical precision and strategy: foil will turn you into a torso tactician.

- You prefer speed and aggressiveness: saber offers rhythm and spectacularity.

- You are attracted to realistic dueling and distance management: epee forces you to think about the entire body and assume the possibility of double touches.

Comparative table of physical and mental demand

| Aspect | Foil | Saber | Epee |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | High (fine) | Very high | Medium |

| Endurance | Medium | High (intensity) | High (concentration) |

| Reflexes | Very high | Extreme | High |

| Tactics | Crucial (priority) | Crucial (tempo) | Key (patience) |

Technical training: recommended exercises

Some exercises that should not be missing in a club session:

- Footwork: short movements, rhythm changes, and recovery.

- Aiming drills: short series of thrusts and marked targets for precision.

- Parries and ripostes: repeated practice until the response after a parry is automated.

- _Speed circuits: weapon shadow fencing, explosive sequences, and short breaks.

Equipment and accessories: what you need to get started

Beyond the weapon, clothing and protections are fundamental: mask, plastron, glove, jacket, and trousers. In foil, a metallic plastron is used to register touches; in saber and epee, the system and connections vary according to regulations.

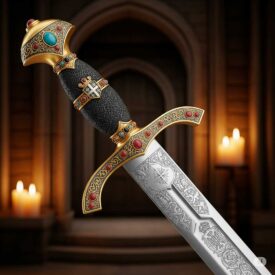

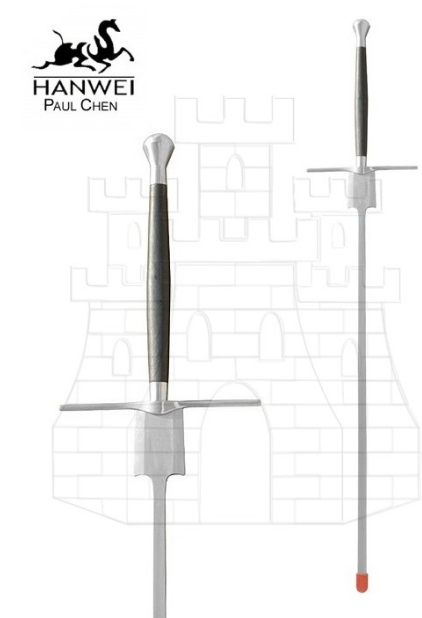

Brief history of modern weapons and their lineage

Modern fencing weapons come from distinct traditions: the modern epee from the French smallsword and the rapier; the foil was born as a training weapon for thrusting; the saber derives from cavalry military sabers that brought cutting as an effective technique. Each of these roots explains its current technique and regulations.

Tips for the practitioner who wants to progress

- Train the basics: footwork, posture, and aiming account for 70% of progress.

- Work with a stronger opponent: it forces you to improve tactical reading.

- Analyze your bouts on video: visual feedback accelerates learning.

- Do not neglect physical preparation: strength, power, and endurance make a difference.

Auxiliary table (key features)

| Feature | Foil | Saber | Epee |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valid area | Torso | Waist up | Entire body |

| Competition type | Convention (priority) | Convention (priority) | No priority |

| Bout rhythm | Medium | Very fast | Variable |

Fencing today: innovation and identity

Modern fencing combines tradition and technology: equipment has improved in safety and recording precision, while national schools contribute differentiated styles that enrich the discipline. The fencing community values both technical excellence and the history behind each weapon.

VIEW SABERS | VIEW FOILS | VIEW CUP-HILT RAPIERS | VIEW LOOP-HILT RAPIERS